In the Shadow of Woburn

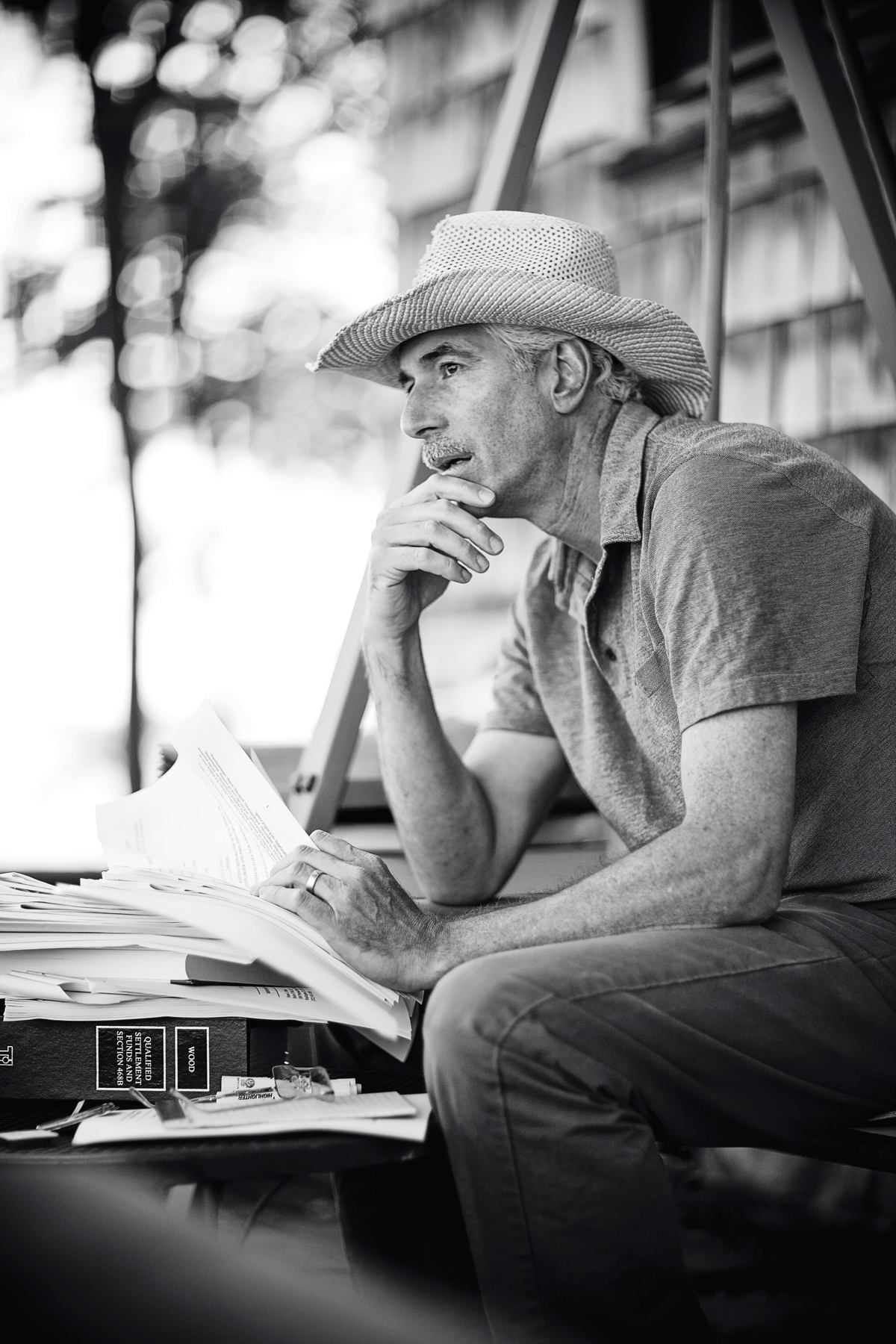

Photograph by Carl Tremblay

The hearing is not going well for Jan Schlichtmann. He’s back in Woburn, the town that scarred him, drove him to madness, altered him forever, and then, still later, made him famous. Woburn has changed a great deal in the 23 years since the jury reached its decision in Anne Anderson v. W. R. Grace & Co., the case chronicled in A Civil Action, the best-selling book by Jonathan Harr. The tannery and chemical plant that poisoned the water are gone now, and the Middlesex County Courthouse itself moved to a commercial zone of office suites and chain restaurants right off the freeway. The cubicle farms are intended to show the progress of this blue-collar town, but they also lessen the gravitas of the court’s proceedings.

Up on the seventh floor, in a room packed with more reporters than plaintiffs, Schlichtmann stands before the judge, just as transformed as Woburn. Gone are the Hermès silk ties, the Bally shoes, the suits that Schlichtmann would travel to New York to have tailored. In their place are a blue shirt and red tie (the only tie his friends know him to own), a navy blazer poorly matched with gray slacks, and black shoes that, from the gallery, look to be some hybrid version of tennis sneakers.

Schlichtmann is no longer the trial king, either, and hasn’t been since the demoralizing Anderson verdict. He looks to settle cases now, which is why he’s here today, seeking injunctive relief: a court order for a party to stop acting in a certain manner. In this case, that party is the Massachusetts Turnpike Authority, which Schlichtmann sued this spring. He contends that the Turnpike Authority is unfairly burdening commuters who travel into Boston on I-90, and through the Sumner and Ted Williams tunnels. More than half the toll fees these commuters pay are going not to the roads and tunnels they travel every day, but to the Big Dig debt, now standing at $15 billion. Meanwhile, commuters traveling on I-93, through the center of the Big Dig, pay nothing, because I-93 isn’t a toll road.

The case involves the sorts of public-policy arcana that would, in lesser hands, make the pages of the complaints read so dry as to become brittle. But under Schlichtmann’s pen, the case is epic. What we have here is a modern-day retelling of why the patriots of centuries ago (and right here in Boston, mind you!) fought back against the English: taxation without representation! And Schlichtmann will battle accordingly.

He’s on to something, fighting along such broad lines. If he wins or, more probably, settles to his liking, the case will rewrite not only legislation in Massachusetts—which in 1997 passed the law that set up the Big Dig repayment plan—but also legislation throughout the country. In New York, for instance, two-thirds of the revenue from the city’s toll bridges and tunnels goes to support its subway system. If Schlichtmann prevails in Massachusetts, he’ll have grounds, in theory, to take his equitable-toll-road argument anywhere else.

And he’ll bring the suits his way. Woburn taught Schlichtmann many things. Chief among them: The practice of law is “diseased,” he says, crowded with litigators out to destroy each other first, and resolve their differences later. In the two decades since Anderson, Schlichtmann developed and then refined—some might say perfected—a technique that keeps his cases largely out of the legal system: He establishes a public trust through which the assumed plaintiffs air their grievances and the facts they’ve uncovered (where Schlichtmann comes in) directly with the assumed defendants. The idea is to mediate before the sides litigate, and when it’s done well, Schlichtmann turns to the court only to approve the settlement.

That’s why today is important. If Superior Judge Herman J. Smith orders the Turnpike Authority to stop siphoning toll revenues away from toll roads, Schlichtmann can force the agency to the negotiating table, a place it’s heretofore refused to sit, and have its lawyers mediate with him and the co-counsel from the case’s trust, the Massachusetts Turnpike Toll Equity Trust. Some 2,500 people have joined the trust since Schlichtmann filed suit in May; it is seeking $450 million in damages.

That’s a lot of money for a lawsuit in which no one died. And to hear Schlichtmann’s critics—who are as numerous as they are vociferous—tell it, the settlement he wants in this case is proof that he’s simply another greedy trial lawyer. No, worse, because Schlichtmann does not bring his cases to trial. Greed, say the critics, many of them well-paid lawyers themselves, was the real lesson of Woburn. Indeed, part of the reason this afternoon’s hearing is at times rough for Schlichtmann is because of the Turnpike Authority’s young lawyer, Brian Kaplan, who seems to relish repeating the nasty perceptions of his opposing counsel. Schlichtmann has a choice, Kaplan says. He can argue today that the harm to his clients is irreparable, a violation of the Constitution, which would satisfy the criteria for injunctive relief. But he can’t satisfy those criteria by arguing along constitutional lines and asking for money. Thus, Schlichtmann’s choice: Take the high ground and ignore money, or get dirty and talk about it a lot. “To put that choice to Jan Schlichtmann,” Kaplan says, staring at Judge Smith, “he’d take the money.”

Some members of the gallery snort at this, and the judge briefly raises his eyes toward them. At Schlichtmann’s table, you can see the back of his neck redden.

When it’s Schlichtmann’s turn, he stands to address the judge. He is 58 now, tall, with a prominent nose and mustache, his face gaunt enough to look haunted, his frame as thin as when the evening-news cameras first captured it a generation ago. His hair was graying then, and it’s nearly white now, but some things haven’t changed. He is still such a zealous advocate for his cases that he’d rather they be referred to as his “projects.” Projects are causes. Cases are what lawyers bill hours for. Projects are the lawsuits Schlichtmann believes in, because through them he can honor his most basic passions: to right wrongs and, even more fundamental, to expose the truth.

In response to Kaplan’s quip, Schlichtmann reads back to the young lawyer, in a voice the next courtroom can hear, parts of a reform bill that the governor has just signed that show, to Schlichtmann, the injustice of the Turnpike Authority’s toll fees. “Even the legislature is in agreement, judge!” he shrieks.

At the end of the hour, having heard enough from both sides, Judge Smith stands to leave. He has decided to enter his ruling at a later date.

Schlichtmann takes the opportunity to go outside and talk to reporters. When asked about the Turnpike Authority’s strategy, he says the agency had showed that, in its view, “[it’s] free to rape and pillage the land.” This is presumably the first time a quasi-governmental agency charged with collecting change has been accused of making like Attila the Hun. But Schlichtmann doesn’t crack a smile at this. He just stares the reporters down.

Woburn, it seems, changed Schlichtmann in many ways—except the most important one.

In December 1985, a few months before the Anderson trial began, Schlichtmann’s grandmother died. Her funeral fell on a Sunday, but Schlichtmann spared only an hour to attend. That was how much the case consumed him.

He came to the law as a life insurance salesman turned ACLU exec, a 23-year-old from Framingham who had watched the Watergate hearings and wanted to do something equally meaningful. Something that might effect change. As author Jonathan Harr eventually chronicled so well in A Civil Action, Schlichtmann was a brash young lawyer after Cornell Law, brash enough to have turned down a $75,000 settlement offer in his first trial—a wrongful-death case, one that even the judge thought should be settled. He ended up winning roughly $300,000 in damages. Brash enough, too, to open his own firm at age 31 with two friends, Kevin Conway and Bill Crowley.

Schlichtmann, Conway & Crowley, on Milk Street in the Financial District, and just steps from the waterfront—it felt like Schlichtmann had arrived. He threw a huge bash shortly after he had the office renovated. Hundreds of people attended. Waiters in black tie served champagne. Traffic backed up for hours while a crane hoisted a grand piano through the second-story window. This was the Jan Schlichtmann of the 1980s: In the era of greed, he was as ostentatious as a Wall Street broker—he drove a black Porsche, lived on Beacon Hill, and bought furniture for the office from a former White House designer—but also so obsessed with his cases that he took only one at a time, the better to focus his energy.

That helped Schlichtmann become very, very good at what he did. In one case, he sued Massachusetts General Hospital, arguing that an infection had eaten away the hip bone of a man named Paul Carney, who’d come to MGH after a car accident. The biggest plaintiffs firm in New York had already turned down the case, as had two Boston firms. They viewed it as too complicated, the chance of victory too slim. Plus, the defendant was MGH, one of the greatest hospitals in the world. No matter: Schlichtmann received a $1 million settlement offer from MGH’s lawyers right before the trial. He turned it down. Lawyers around town whispered about the crazy young attorney who had refused a million-dollar settlement from MGH. Schlichtmann took the case to trial and won $4.7 million. It was thought to be the largest malpractice award in Massachusetts history.

Woburn was his next case.

In East Woburn, eight families had lost children to leukemia over a span of two decades. Two of the town’s drinking wells were found to contain many toxins. Schlichtmann contended that two nearby companies, the W. R. Grace chemical plant and the John J. Riley Tannery, had dumped their chemical waste onto the grounds of their properties, sometimes in 50-gallon drums, and that waste had seeped into the drinking wells. Once in the drinking supply, Schlichtmann argued, the concentration of chemicals had been high enough to have caused the cancer that killed the children.

It was a bold claim, made all the bolder because environmental law was in its infancy then, the link between chemicals and the cancers they caused legally irrelevant if not nonexistent. When Schlichtmann’s firm took up Woburn in 1982, for example, none of the Big Tobacco lawsuits had been settled yet. One day, deep into the discovery phase of the Woburn case, Schlichtmann learned how delusional his cause really was.

He’d flown to Illinois to court a cancer expert from the University of Chicago. Schlichtmann still remembers the academic asking him, once he’d reached the university’s lab, “Do you have any idea what you’re trying to do here?”

“What do you mean?” Schlichtmann asked.

“Let me explain something to you. See that big computer room over there? If I came here today and told it, ‘Please spit out all the studies that have been done connecting cigarette smoking with cancer,’ I couldn’t come back here in a day. I couldn’t come back here in a week. I would come back in one month’s time and there would be tens of thousands of studies. Now let me ask you, Mr. Trial Lawyer: How many cases have been won where it was proved that cigarette smoking causes cancer?”

“None.”

“Now, next question: If I go to the same computer and I say, ‘Please print out all the studies that have been done showing that exposure to these chemicals in water causes cancer in children,’ we wouldn’t have to wait a month, or a week, or an hour. The computer would say, ‘There are none.’ Understand? Tens of thousands—you still can’t do it. And you want to do it with none?”

On the flight back to Boston, well into his second scotch, Schlichtmann thought, What are you going to do? Go back and say to the families, “There are no studies?” He knew what they’d say, outspoken mothers like Anne Anderson, the lead plaintiff in the case: “Our children are the study.” That was what he believed, too. And he would not back away from his version of the truth, from his sense of what was right. Just because the science didn’t exist didn’t mean it never would.

In the end, huge swaths of original scientific research in geology, epidemiology, and even cardiology were funded not by the federal government, not by wealthy nonprofits, but by Schlichtmann’s tiny law firm on Milk Street—independent scientific inquiry whose results could have helped either side in the Woburn case. A great deal of it just happened to support Schlichtmann’s. Which was a very lucky thing. The firm spent $2.6 million preparing for trial.

It may have been valiant to spend that much on research, but it was also stupid. As A Civil Action would show, Schlichtmann, Conway & Crowley took out an ever-growing number of loans and maxed out credit cards just to bring the case. Before it was over, secretaries and paralegals were working without pay. Crowley had to use his Westwood home as collateral for a loan for the firm. Conway had to use his Wellesley home as collateral—twice. (His wife still refuses to go to the annual Woburn gatherings for this reason.) Schlichtmann fell behind on his mortgage and started living in the office.

But none of the partners regretted the case. Not when they were in it. Back then, Schlichtmann’s motto for the firm was “Rich, famous, and doing good.” The Woburn case would make them rich and famous, and it would do a great deal of good: create a landmark precedent, but also change corporate behavior and, by extension, the culture of America. This would be Schlichtmann’s chance to finally effect change on a grand scale.

This sort of change does not come easily, though. In the Woburn case, the opposing counsel, Jerome Facher, a senior partner at the Boston law firm Hale and Dorr and a lecturer at Harvard Law School, convinced Judge Walter Skinner to break the immensely complicated trial into two parts. Officially, it was Skinner’s decision; such was the case’s complexity, he reasoned. But the bifurcation benefited Facher and the defense attorneys for W. R. Grace in two ways.

First, it gave the defense teams two trials, which put an added burden of proof on Schlichtmann. The first phase of the trial would test the scientific validity of the plaintiffs’ claims. Were the tannery and W. R. Grace responsible for the wells’ contamination? If the jury believed that, the case would move on to the next question: Were the chemicals in the water responsible for giving the children cancer?

Second, delaying the medical portion meant Schlichtmann couldn’t put the Woburn families on the stand until the trial’s latter phase. Their tragic losses were his most compelling pieces of evidence. And now, if he wasn’t successful in the first phase, the families wouldn’t take the stand at all.

Facher worked to ensure that. The trial opened in March 1986 and lasted until late July—79 days of testimony, evidence, and Facher’s objections and ruthless cross-examinations. Already Facher had succeeded in taking a case about dying children and turning it into one of soil samples and river flow, with academics making competing, esoteric claims. But during Schlichtmann’s closing argument, Facher also broke the gentlemen’s agreement among the lawyers, and objected throughout. Schlichtmann had stayed up all night writing and rewriting and muttering into memory his speech. Facher’s objections threw him off. He lost focus, kept losing his place. What was clear and convincing the night before became like so much in this trial: muddied by Jerry Facher’s deft hands.

The jury found the tannery that Facher represented not guilty. The W. R. Grace chemical company, however, was guilty. But with little money and almost no chance of success in a second phase of the trial, Schlichtmann’s firm settled with W. R. Grace for $8 million. This infuriated lead plaintiff Anne Anderson, who had just wanted an apology. Now, because of a stipulation in the settlement agreement, Grace would admit no wrongdoing. She came to believe that Schlichtmann took the case only to advance his career and his bottom line. How else to explain the firm’s $2.2 million in legal fees—40 percent of the settlement, after expenses?

The low point for Schlichtmann was not his lead plaintiff calling him greedy, though. It wasn’t, after the threat of a lawsuit, repaying Anderson and another family $80,000 in legal expenses that an accountant believed to be frivolous. It wasn’t, after all the other lawyers had been paid, making only $30,000 from the case, which wasn’t enough ultimately to pay his debtors. It wasn’t seeing his Porsche repossessed, or even his furniture, too, and living like a squatter, making his bed at night with two chair cushions the repo men hadn’t taken. No, the low point, he realizes now, came when he found that Facher’s firm seemed to have withheld evidence, a revelation that essentially allowed him to retry the case. Only in hindsight would Schlichtmann see that another shot at Anderson would prove as toxic as the Woburn water itself.

In appealing the decision in favor of the tannery, Facher’s client, a lawyer working with Schlichtmann came across a report that showed the company had dumped waste down a nearby hill. The waste then sifted its way into the groundwater, where it looked a lot like a contaminant that one of Schlichtmann’s experts found there years later. The report was the keystone of Schlichtmann’s argument.

He took the charge of withholding evidence, ultimately, to the U.S. Court of Appeals. In December 1988, more than two years after the initial verdict, the court agreed with Schlichtmann. The case went back to Judge Skinner, who was instructed to issue a legally binding report of his findings for the Court of Appeals.

Schlichtmann produced new witnesses: people who worked at the tannery and saw the dumping. He would also reveal that the tannery’s in-house attorney, Mary Ryan, had withheld the report. Ryan alleged in an affidavit that Facher’s firm knew about the report, too, and knowingly withheld it. Meanwhile, John J. Riley, the tannery’s former owner, had admitted lying under oath during trial.

Skinner’s hearings lasted from January through October in 1989, longer than the trial itself. It took him two months more to issue his findings. Schlichtmann walked to the courthouse with Bill Crowley that December morning, jumpy with nerves. Skinner wrote that Ryan had, in fact, concealed the report. Yet, using logic that Schlichtmann still finds circular, Skinner said Schlichtmann had brought a frivolous case to trial because he worked without all the evidence available: namely, the report that had been kept from him. The case was over.

Michael Keating, an attorney at Foley Hoag, part of the legal team that represented W. R. Grace, says Schlichtmann’s fatal flaw is his inability to separate a cause from the case before him. “When you are so imbued with a cause,” Keating says, “you forget what you’re really representing. I felt that the clients didn’t have the priority in his mind that they should have had.” What Keating is referring to is a settlement Schlichtmann had offered the defense before the Woburn trial: a $175 million deal, one that would serve as a political milestone and, Schlichtmann surmised, deter any other corporation that thought of acting similarly. The defense, however, took one glance at the settlement that day and walked out of the room. But what Schlichtmann didn’t know then, according to one defense attorney from Anderson, was that he could have had a huge victory that afternoon. The defense had been ready to hand the eight blue-collar families from Woburn perhaps as much as $40 million.

After Woburn, Schlichtmann blamed his problems with the case on Judge Skinner. After Skinner’s final decision, according to A Civil Action, he yelled in the courthouse, “The man is a fucking monster!” Schlichtmann shook with rage, and would not stop shaking for five years.

Schlichtmann calls this time his “wilderness years.” Woburn was his life and his life had been deemed a failure. And not just by Judge Skinner, either. In 1990 Schlichtmann appealed his evidentiary findings all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. He couldn’t convince anyone of his version of the truth. He’d dedicated nine years to the case, nine years. He’d bankrupted himself, in every sense of the word. He at one point had $114 to his name and $1 million in debt; he’d lost so much weight during court proceedings that he looked like a refugee.

Schlichtmann said he was done with the law. A friend loaned him money so that he could escape to Hawaii, where he began selling energy-efficient light bulbs.

Not surprisingly, Schlichtmann views his own story in terms of extreme, dichotomous themes. He moved to Hawaii but couldn’t lose “the hollowness” inside, he says. He sensed that the rest of his life would offer nothing but pain and failure. He hiked a lot, thinking that might help. He enjoyed hiking. One late afternoon, deep into a daylong trek through the Big Island’s northern jungle, he came across a stream that “had this music to it,” he says. It had rained that afternoon, and the leaves around him were a surrealist green, heavy now with water, spilling droplets one at a time. And the sun reflecting off the stream— Schlichtmann thought the scene was stunning, the most gorgeous he’d ever witnessed. Or rather, he thought that he should be thinking this. Because in reality he couldn’t feel any of it. He couldn’t allow himself to enjoy it. And so he cried right there along the bank.

Schlichtmann returned to the law, slowly, intermittently, and only because he couldn’t not go back. He was a lawyer at heart. For all the pain, this was what he enjoyed doing—even if it caused more pain. But he was a different lawyer. In one case, the court found him to be so angry (sneering at the judge and slamming onto the clerk’s table exhibits that had received an unfavorable ruling) and so reckless (repeatedly and “flagrantly,” the court found, asking questions and entering evidence it had ruled inadmissible), that it barred Schlichtmann from practicing in Hawaii. (Ever the zealot, he appealed twice and had the ruling overturned by the state’s Supreme Court.)

What Schlichtmann couldn’t shake, as he dropped all pretense of being anything but a lawyer and shuttled between Hawaii and Massachusetts in the early 1990s, was this idea that the system was corrupt. How else to explain that while his Woburn case had foundered, the EPA, on the strength of his evidence, had ordered the Woburn tannery and chemical plant, among others, to spend nearly $70 million cleaning up their sites? The legal system was “diseased”—that’s the word Schlichtmann kept using now—the truth sickened and made weak by arguments that may win the day in court but have no bearing on what the case is trying to resolve. Schlichtmann felt like a sucker. He felt lost.

That is, until he had the good sense to marry Claudia Barragan. “It took me a long time to appreciate: There’s just not going to be any other human being in the world I’ll be luckier to meet,” Schlichtmann says of his wife. “She was there for me at the most desperate time in my life. She sustained me, and fed me and housed me and loved me and made me believe in myself, and then when I stopped believing in myself, she wouldn’t let go.”

He can go on like that all day. The way he tells it, Claudia was a woman of unending forbearance and grace, gently healing all the chaotic and ultimately destructive elements in the house of Schlichtmann. But Claudia doesn’t remember herself approaching sainthood. A lot of the time, Schlichtmann pissed her off. By suddenly moving to Hawaii with little warning and no regard for the four years the couple had spent together. Or by, after they later got back together in Massachusetts, suddenly moving his things out again while she was at the hair salon.