Ted Kennedy’s Living History

By Francis Storrs

With additional reporting by Ian Aldrich, Matthew Reed Baker, Rebecca G. Dorr, Paul McMorrow, Jason Schwartz, and Brigid Sweeney

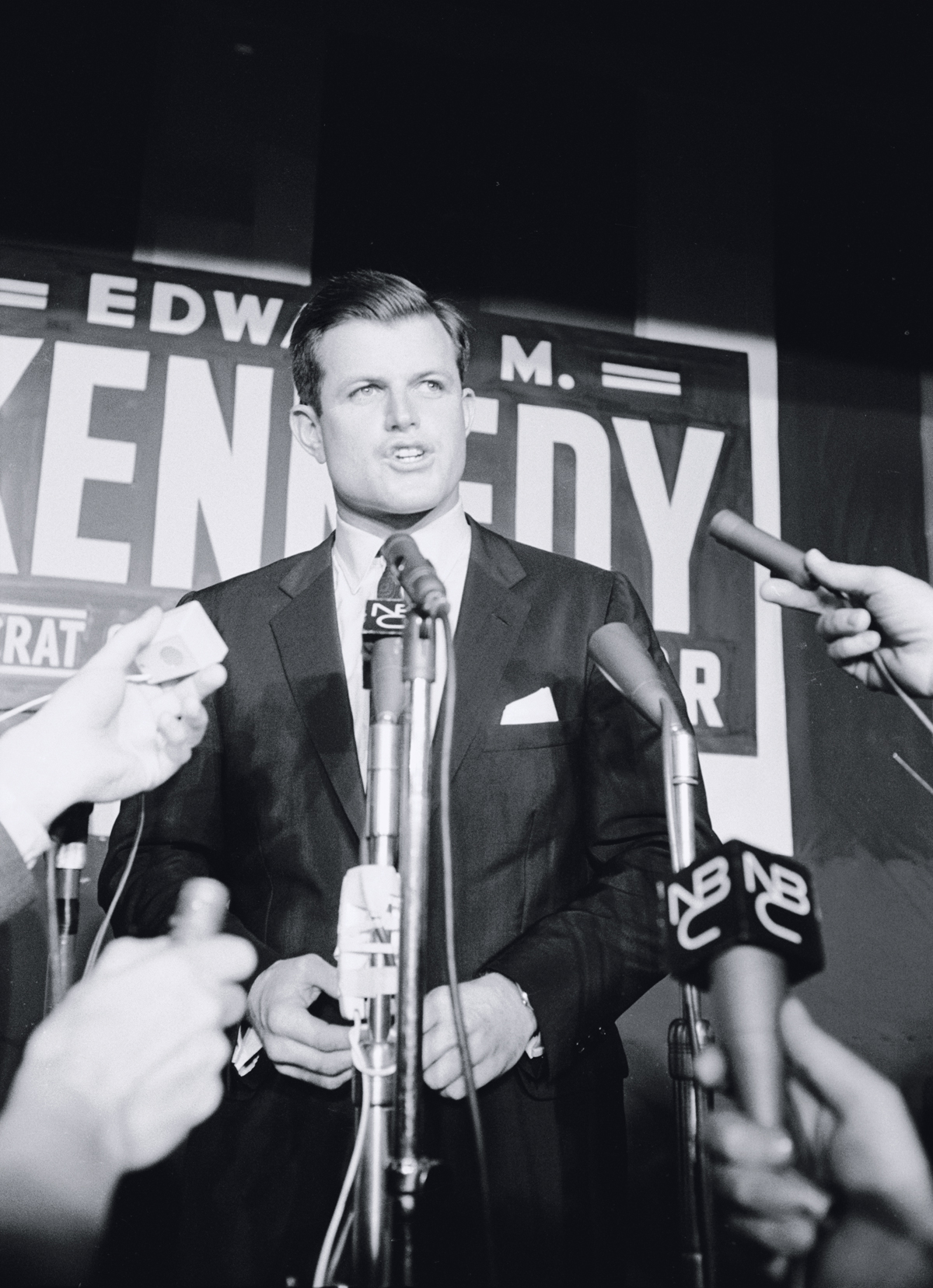

Photograph Courtesy The John F. Kennedy Library

Edward Kennedy, the last of Joe and Rose Kennedy’s nine children, was born in Dorchester in 1932. By then, the family was well on its way to becoming an American dynasty. Joe was a tycoon who, in 1938, became a U.S. ambassador, and young Ted enjoyed a world of privilege. He charmed the king and queen of England and received his first Communion from the Pope. But in a clan of athletes and scholars, Ted was neither: He was a chubby boy who often received poor marks from the prestigious boarding schools he attended. He didn’t give his family much reason to believe in him. “You can have a serious life or a nonserious life, Teddy,” his father famously warned him early on. “I’ll still love you whichever choice you make. But if you decide to have a nonserious life, I won’t have much time for you.”

Though Ted Kennedy would never forget those words, it would take years for him to decide which path he would take. He was temporarily expelled from Harvard for cheating on a Spanish exam. His first marriage collapsed amid rumors of infidelity. He was quick to take solace in alcohol. Most destructive of all was his decision, late on the night of July 18, 1969, to drive off from a party on Chappaquiddick Island with a young woman named Mary Jo Kopechne.

And yet Kennedy survived all this by first asking for forgiveness—and then earning it. Over nearly half a century in the Senate, he authored some 2,500 bills, and his name was on more than 850 that became law. They improved the lives of the young and old, the well and the infirm, the soldiers who waged war and the students who protested it. “He led with his heart,” says John Kerry, now the senior senator from Massachusetts. “It was the biggest of hearts.”

After Kennedy’s death in August, thousands of people lined the roads along which his body traveled from Hyannisport to Boston; tens of thousands filed by his casket at the Kennedy Library. They came to pay their respects and to say goodbye, but also to do something more: to recognize that Kennedy was the one brother who lived long enough to reconcile his failings with his triumphs, and that his life, though outsize, was so very human.

To capture the depth and breadth of Ted Kennedy’s extraordinary career, we spoke to more than 65 of those who knew the man best, from his college years to his final days.

Reid Moore, University of Virginia law school classmate: He had independent wealth. He lived a more dramatic life than most of us. That translated to an Oldsmobile convertible, often with the top down and large dogs in the back seat.

Mortimer Caplin, law school professor: Jackie once said, “You were Teddy’s law professor! Could you imagine Teddy a lawyer?” He was the kid of the family. In a way, they didn’t take him seriously.

George Abrams, Harvard classmate and Kennedy aide: He served as assistant district attorney and tried a few cases, not major criminal trials. One was appealed; the defendant argued Ted Kennedy was too well known and mesmerized the jury.

Adam Clymer, Kennedy biographer: Joe initially was concentrated on planning for the oldest son—first Joe Jr., then after his death, Jack. He wasn’t as precise in his expectations for Ted. But they trained him up to enter politics by making him Jack’s titular campaign manager in 1958.

Dick Tuck, political adviser: It was a title we put on him—that was the extent of his participation.

Claude Hooton, Harvard classmate: We were [campaigning] in Miles City, Montana, and Ted had to go off and meet some people. This guy said to me, “You know, there’s a rodeo in town and 5,000 people will be there. You think he’d ride?” I said, “Heck, he can ride. Hell, he jumps horses—he’s one of the best riders I ever knew.” So Ted and I finally got together at the rodeo. He said, “What am I doing out here?” I said, “Ted, I’ll guarantee your picture in Life.” He said, “What do I have to do?” “To be honest with you, all you have to do is ride a bareback bronc.” “I have to do what?” He was almost speechless. He made six or seven jumps and off he went—he pulled about half the muscles in his crotch. Three weeks later, Life gave him the top half of the page. So, anyway, it had a happy ending.

Hooton: The night after Jack got the Democratic nomination, we were at Peter Lawford’s house in Hollywood for a big party. Everybody was half asleep from the red wine, and Jack told Ted he had to liven it up. Ted came over and said, “Jack said we need to get up and do our numbers,” which we had done for years: “Bill Bailey,” “Heart of My Heart,” and the old Irish songs. When we finished singing, we said, “Anybody in the room who thinks they can do better, come on up here.” So Frank Sinatra stood up and walked over to the band. Then, on the other side of the room, Nat King Cole got up. I said to Ted, “Maybe we should have just quit when we were ahead.” For the climax, Judy Garland sang “Somewhere Over the Rainbow.”

In November 1960, John F. Kennedy defeated Richard Nixon for president by two-tenths of a percentage point in the popular vote, one of the slimmest victories in U.S. history. Upon assuming office, Jack immediately appointed his brother Robert as attorney general, though he declined to give Ted the State Department job he had asked for. At his father’s urging, Ted would run for the Senate in 1962 (after he had reached the required age of 30). But before he could take on the state’s formidable attorney general, Edward McCormack, for the Democratic nomination, his family would need to deal with speculation about why he had been expelled from Harvard in 1951.

Phil Johnston, former state Democratic Party chairman: One brother is the president of the United States, the other one is attorney general—and then, by the way, I have a third one who’s a war hero, and a sister who started this international organization for the disabled. It’s a wonderful thing to have relatives you look up to, and it’s a burden in that you might feel that you’re not successful if you’re not president by the time you’re 45.

Tuck: When Ted first announced he was going to run for the Senate, both Jack and Bobby didn’t think it was a very good idea. Their father, who really kind of ran things, said, “You guys got yours. He’s gonna get his.”

Robert Healy, former Boston Globe Washington bureau chief: The rumors [that Ted had cheated on an exam] were widespread at Harvard. Those days, you didn’t go into print unless you could verify it, and Harvard wouldn’t touch it.

Abrams: Ted and the person who took the test for him were friends of mine. I knew they had a problem…[but] I never knew the details of what happened until they were publicized in the campaign.

Healy: I got a call from the treasurer of the Democratic Party. He said, “Can you come down and meet me?” So I did. “What do you know about Teddy and Harvard?” I said, “I know he got bounced out of there.” He went in the other room and made a call to the White House. President Kennedy got on the phone and [asked me to come down]. I met him in the Oval Office and the one point I made was, “Look, he’s gonna have to deal with this. Eddie McCormack will hit him with it.” The president turned to [an adviser] and said, “We’re having more problems with this than we had with the Bay of Pigs.” So they just gave me the whole story, including the records from Harvard that I needed. There was nothing left out, I might add, except the name of the guy who took the exam.

Anne Frate, wife of William Frate, who took a Spanish exam for Kennedy at Harvard: Ted and Bill were both young. It was a two-way street, of course, but I’m pretty sure Ted [apologized] in more than one way. We remained close friends.

Abrams: Ted once came to a class function at Harvard, and one or two classmates went after him pretty hard for even running. People felt Ted was running because his brothers were in powerful positions, and they had set this spot for him.

Gerard Doherty, campaign manager: He had very little what you would call liberal support. Strangely enough, two of the consistent picketers against us were [then Harvard student] Barney Frank and [then state legislator] Michael Dukakis.

Barney Frank, U.S. congressman: My first impressions of him were negative. I was dismissive.

Michael Dukakis, former Massachusetts governor: We thought McCormack had earned it and that Ted should start his political career a little lower on the totem pole.

Doherty: At 7 o’clock one morning we were greeting people outside the Charlestown Navy Yard. We see this guy coming along; he obviously wasn’t a very happy guy. He saw Teddy and he said, “Kennedy, they say you haven’t worked a day in your life.” Teddy and I looked at each other. The guy said, “Let me tell you, you haven’t missed a goddamn thing.”

Milton Gwirtzman, campaign aide: Bobby was running Ted through preparation for the debate. He said, “Tell them why you want to serve the public. Tell them why you don’t want to be sitting on your ass in an office in New York.” Which, of course, was what their father had done.

Donald Dowd, campaign aide: [At the debate] McCormack said, “If your name wasn’t Edward Kennedy, you wouldn’t be sitting here.” Kennedy just listened to it, which was so good because people watching on TV switched and said, “You know, he’s picking on this young Kennedy.”

Gwirtzman: The people in Massachusetts had very good experiences with members of the Kennedy family. There was a tremendous amount of goodwill toward him.

John Kerry, U.S. senator: I had volunteered [on his campaign]…I was intrigued by the energy and idealism President Kennedy had brought to politics. And Teddy was this young, charismatic candidate.

Lily Tomlin, actress: The mother of a friend of mine had been in Boston politics all her life. Her mother used to say you always vote for the Italian—unless it’s a Kennedy.

After beating Edward McCormack in the primary, Kennedy won the general election against Republican opponent George Cabot Lodge II with 53 percent of the vote. Mindful of his political inexperience—and the fact that his brothers would be judged by his actions—he waited more than a year before giving his first speech on the Senate floor. Instead, he won over his older colleagues by leveraging his formidable social skills.

Clymer: Before he was in the Senate, I think he just wanted to be in the Senate. I don’t think he had any particular plan. I mean, he didn’t want to be a senator in order to pass national health insurance or something like that. But once he got there, he took to the place. Possibly being the youngest of nine children helps when you’re dealing with a Senate run by people in their seventies and eighties, as the place was then.

Marty Nolan, former Boston Globe Washington bureau chief: I remember Teddy calling me the first time he met the chairman of the Judiciary Committee, Jim Eastland. He’s looking at Eastland and Eastland says, “You’re the kid brother of the president, huh?” He gets the bourbon out and pours a glass for him and says, “Let’s toast the president!” Teddy told me this and I said, “Well, what’s the big deal?” And he said, “Because it’s 10 o’clock in the morning!” I said, “What’d you do?” And he said, “What do you think I did?”

Abrams: Senator Eastland didn’t agree with some of Kennedy’s major positions, but he really liked Ted. Early on, we were looking for some approvals for our subcommittee. When Eastland saw Ted, he lit up…. We had a good time telling stories, and then Kennedy said, “Well, Jim, we’ve got a couple of authorizations we need from you here.” He said, “Oh, no problem, I’ll sign those.”

Jim Manley, spokesman: The smart senators always knew three things in dealing with Senator Kennedy. Number one: His word is good. Number two: You’re gonna get things done. And third: If you worked with Senator Kennedy, the TV cameras would show up.

Thomas Southwick, spokesman: I remember when he came back from a trip to China, I asked him, “What was it like?” And he said, “It was interesting for me, because I could walk down the street and nobody knew who I was.” I got the sense from him that that was almost a relief.

When JFK was killed in Dallas on November 22, 1963, Ted was working in Washington. He and his sister Eunice flew to Hyannisport to break the news to their father, who had suffered a stroke two years earlier. But Ted couldn’t bring himself to tell his father that night what had happened. “There’s been a bad accident,” he finally told Joe Sr. the next morning. “The president has been hurt very badly. In fact, he died.”

Gwirtzman: Ted had been presiding over the Senate when someone came up to him and gave him a piece of paper saying that Jack had been shot. He tried to reach Bobby on the phone, but he couldn’t get through. Then he tried Joan and he couldn’t get through. The phones all over Washington were overloaded. He began to worry that [his family] was a target. The two of us and Claude Hooton drove from Capitol Hill through downtown Washington to get to his home in Georgetown.

Hooton: The phones weren’t working at his house. We started ringing doorbells; about the fourth house answered. The phone was under some steps in the kitchen. He had to get down on his knees to get to it. The phone worked—it was a miracle. He got Bobby, and I saw him wince.