Boston Sportswriters: The Fellowship of the Miserable

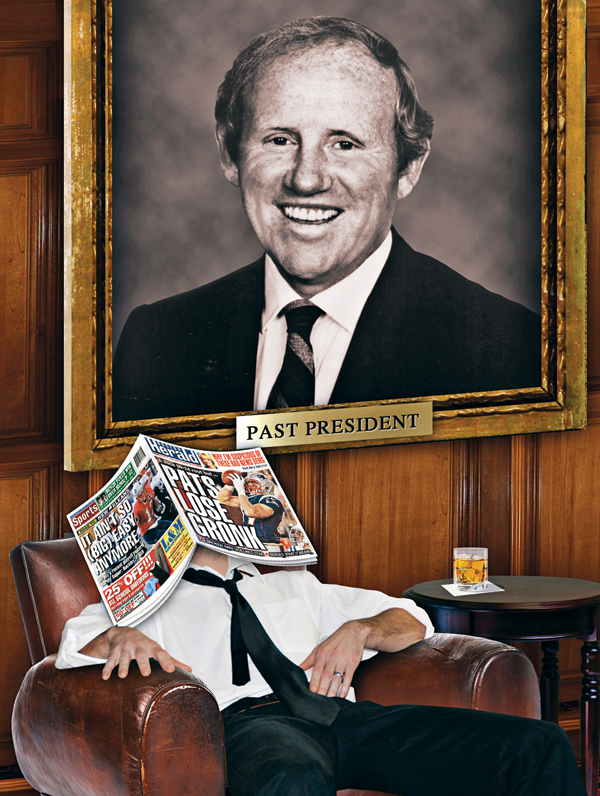

Photo by Landov (McDonough). (Illustration by John Ueland)

Passan’s story was still fresh in Sullivan’s mind. “We got beat,” he told me. “There’s no question.” Then, after carefully making a point to praise the work of his own baseball writers, he added, “It’s like in sports—you’re going to lose some games.” Although his staff has shrunk overall in recent years, Sullivan has increased the number of reporters on the marquee Patriots and Red Sox beats from two to three each. The extra staffing is important to help the paper fulfill what Sullivan says is its mandate in this digital age: “to serve the Web and print at the same time.”

As forward-thinking as that sounds, the newspaper’s core approach to sports coverage—which still relies on boilerplate game recaps, columns, and weekly “notebooks” offering bullet-point takes on the happenings from the various sports leagues—hasn’t changed much over the years. In fact, not much in the Boston sports media has—not even the photos on the wall.

How did we get to this point? Ironically, it’s the success of this city’s sports-media past that is at the root of today’s problems. Romanticizing the Globe of the ’70s and ’80s has become almost clichéd…and for good reason. Back then, the paper had a must-read sports section featuring, among others, Peter Gammons, who pioneered the baseball notes column; Bob Ryan, whose knowledge of the Celtics’ playbook rivaled that of the team’s head coach; the late Will McDonough, an NFL insider from Southie who was one of the first print reporters to appear regularly on television; Leigh Montville, a wordsmith who eventually moved on to Sports Illustrated; and Jackie MacMullan, a pioneering female columnist and feature writer who’s still one of the greats.

Today, the paper’s sports section remains synonymous with Ryan, now semiretired, and his fellow columnist Dan Shaughnessy. Glenn Stout, the editor of the Best American Sports Writing series and a longtime New Englander, says, “a place like the Globe hasn’t had a turnover of voices in 20 or 30 years.”

Since columnist Michael Holley left the paper for a radio gig at WEEI eight years ago, it’s hard to think of a single distinctive voice the paper has developed and held on to. Meanwhile, the Globe has continued to employ a number of longtime veterans, like Cafardo, who seem to have hung around forever.

It’s a similar story over at the Herald, where old mainstays like Gerry Callahan and Steve Buckley continue to occupy top billing. The tabloid’s also had Mark Murphy and Steve Bulpett covering the Celtics since the days of short shorts, and it even hired Ron Borges as a columnist after he departed the Globe following a plagiarism scandal. Meanwhile, sports talk radio station WEEI has stuck with many of the same hosts they’ve had since the ’90s, like Callahan, John Dennis, Glenn Ordway, and even Mike Adams. It’s not that all the old-timers are bad—it’s more that it’s bad that there are so many old-timers. Bill Simmons, the ESPN media mogul and star columnist, has often complained that he never felt like he, or any young, aspiring writer, had a fair chance to break into covering Boston sports.

And it’s not just the city’s core sports personalities that haven’t changed much. The way the local media covers games is stuck in the past, too. Beat writers may blog, chat, and utilize social media now, but after games, they’re still churning out the same kinds of vanilla recaps that have long been a newspaper staple. While these types of stories have the capacity to be poetic—Gammons’s lyrical piece after Game 6 of the 1975 World Series is considered the modern standard—today’s versions rarely rise to such levels and, in the end, just end up rehashing hours-old events (as if the highlights weren’t immediately available online).

In most game stories, there’s a conspicuous lack of creative analysis, which is compounded by the local media’s apparent allergy to the type of advanced statistics that other outlets have used to shine new, interesting light on old sports. For instance, after the Patriots earned a spot in the AFC Championship game by beating the Houston Texans in January, the Herald dutifully recapped the series of events in the game, sprinkling in quotes like Tom Brady saying afterward, “I’m tired, man.” (One would think so!) Tight end Aaron Hernandez offered this enlightening bit of pablum: “We’ve still got one more to go to get to the big dance, so we’ve got to keep playing and come to play next week.” And defensive standout Vince Wilfork was captured saying, “It’s sweet playing in the AFC Championship.” Another big shocker. Meanwhile, the sharp minds over at the national website Pro Football Focus informed their readers that the Texans blitzed on 48.8 percent of their plays, a decision that allowed Brady to pick their defense apart. When Houston did get to Brady, he was 0 for 5 on completions, but those occasions, the site reported, were rare. The difference between the two approaches was night and day.

WEEI.com’s Alex Speier, who specializes in incorporating advanced stats into articles meant for the average fan—and who is therefore one of the city’s few inventive sportswriters—told me that everything has changed now that readers no longer depend on print for all their news. “Now you have to wrestle with whether what you’re doing is interesting,” Speier said, “or a bit of a nuisance.”

It’s not as though the local sports press exists in a total time warp. TV, radio, and the Internet all have a big presence in the media landscape. It’s just that too many of our sportswriters—ahem, sports “personalities”—have become adept at using these 21st-century tools to serve up what is little more than the same old slop. Take Dan Shaughnessy. After his more than 30 years at the Globe, everybody knows the columnist’s shtick: Be contrarian, be over the top, and, if at all possible, be part of the story. And why should he change? It continues to work—the rest of the city’s sports-media complex feeds on his bluster. Before that Texans game, for example, Shaughnessy used his column to gleefully ridicule the Patriots’ opponents, calling them “pure frauds.” It was the same caustic, one-liner-laden junk he’s been peddling for years. “Could this get any easier?” Shaughnessy wrote. “I mean, seriously? The planets are aligned and the tomato cans are in place.”

Predictably, it provoked a strong reaction. First, the football writer Tom E. Curran, of Comcast SportsNet New England, took to Twitter, writing that “Shaughnessy couldn’t name 5 Texans. Or 10 Patriots.” Then, right on cue, Shaughnessy appeared on The Sports Hub’s Gresh & Zolak show, on which he managed to name five Texans and 10 Patriots. Meanwhile, Texans running back Arian Foster fell into the columnist’s trap, using Twitter to call attention to Shaughnessy’s trolling foolishness.

Later that week, the New-Hampshire-based sports-media critic Bruce Allen summed up the entire episode. “Columns are written, statements are made simply to generate buzz. Good or bad, it doesn’t matter,” he wrote on his website, Boston Sports Media Watch. “By bringing them up and even attempting to denounce them, I’m simply feeding the monster and adding to the buzz.”

That monster, it should be noted, was born out of something fairly benign. When Will McDonough, Bob Ryan, and Peter Gammons began showing up on TV, they evolved from working writers into celebrities. Jackie MacMullan remembers Larry Bird once saying, “Bob Ryan, he’s as famous as we are.” Butover time, the city’s sports punditocracy has expanded to include not just the truly wise, like Ryan, but any sportswriter willing to blow hot air. Glenn Stout told me that, 20 years ago, he might have been able to come up with a dozen Boston sports-media personalities. Now he counts three dozen. “If you’re a halfway decent beat writer in this town,” said Mike Felger, cohost of the afternoon show on The Sports Hub and a CSNNE anchor, “you’ll get on Comcast, or NESN, or Sports Hub, or ’EEI.”

Felger, of course, should know. He’s transformed himself from a sharp Patriots reporter for the Herald into a contrarian “media personality.” His radio cohost, the former Red Sox reporter Tony Massarotti, has done the same thing, if somewhat more shrilly. The primary goal for reporters seems no longer to be merely producing great and interesting work. These days, they’re all trying to be loud and provocative so they can become fixtures on TV and radio. There’s good money, after all, in broadcast. “There has to be a willingness to put yourself out there and make statements without knowing what you’re talking about,” Rich Levine, an online columnist for CSNNE, told me. “You have to not give a shit about ultimately looking like an idiot or saying a lot of things that you regret.”