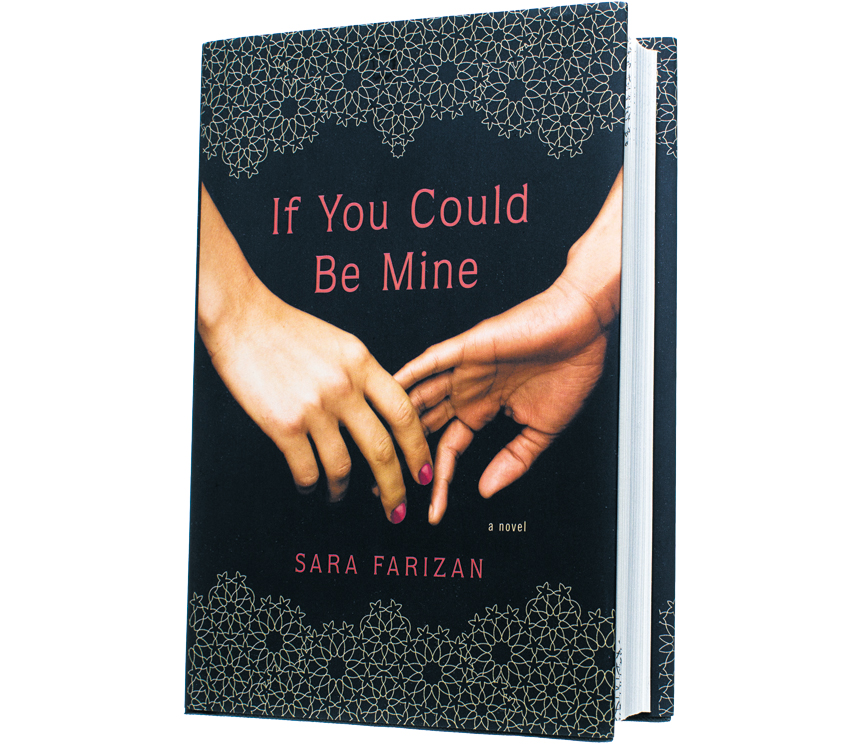

Love Unveiled: If You Could Be Mine, by Sara Farizan

Photograph by Scott M. Lacey

It’s a curious reality of modern Iran: In a country where homosexuality can be punished by death, transgender Iranians may change sex, often at state cost. Under this system, which exists because of a 1987 fatwa by the Ayatollah Khomeini, some gay Iranians have sought to change their sex—even though they aren’t transgender—in order to live publicly with the person they love. It’s a societal Gordian knot, and with her debut novel, If You Could Be Mine (out 8/20, Algonquin Young Readers, $17), author Sara Farizan seeks to untangle it with the story of a teenage lesbian in Tehran who’s considering sex-reassignment surgery.

For Farizan, now 29, growing up gay in Massachusetts was far less perilous than it would have been in Iran, but it certainly wasn’t easy. Her parents emigrated from the country in the 1970s and settled in West Newton, where Farizan grew up watching cartoons, like any American kid—but even then, she knew to keep quiet about her inchoate crushes on female characters like Belle in Beauty and the Beast. She stayed deeply closeted all through her high school years at Noble & Greenough.

“A lot of my adolescence was dealing with harboring this big secret,” she says. “I did a lot of extracurriculars. I did theater, I was school president, I was very social. Then I’d walk to my car and cry in the car.”

When Farizan, who’s now out, began writing If You Could Be Mine as her MFA thesis at Lesley University, she felt ready to look back on those years of hiding her identity. The book’s young Iranian heroine, Sahar, is outwardly feisty but inwardly fragile, and in love with her best friend, the beautiful Nasrin. There’s no way for them to be together—unless Sahar pretends to be a transsexual and undergoes surgery.

Farizan describes her book as “a love story, like Juliet and Juliet—on steroids, and in Iran.” For her thesis, she traveled to Tehran and connected with the gay community there. She writes about a discreetly queer-friendly café and clandestine parties, all fictional but based on the city she saw. “It’s really like a very 1950s U.S. way for queer people to meet up,” she says.

With the book’s imminent release, she’s a little worried about how it will be received—not only by the Iranian community, but also the queer one. “This subject is so much larger than me, and I don’t want to seem like I’m the authority on everything in Iran or LGBT there,” she says. “But if this book leads the way for people in small-town U.S.A. to tell their stories, that’s tremendous, and if Western audiences can root for an Iranian lesbian, I think that’s pretty amazing.”