Astral Sojourn

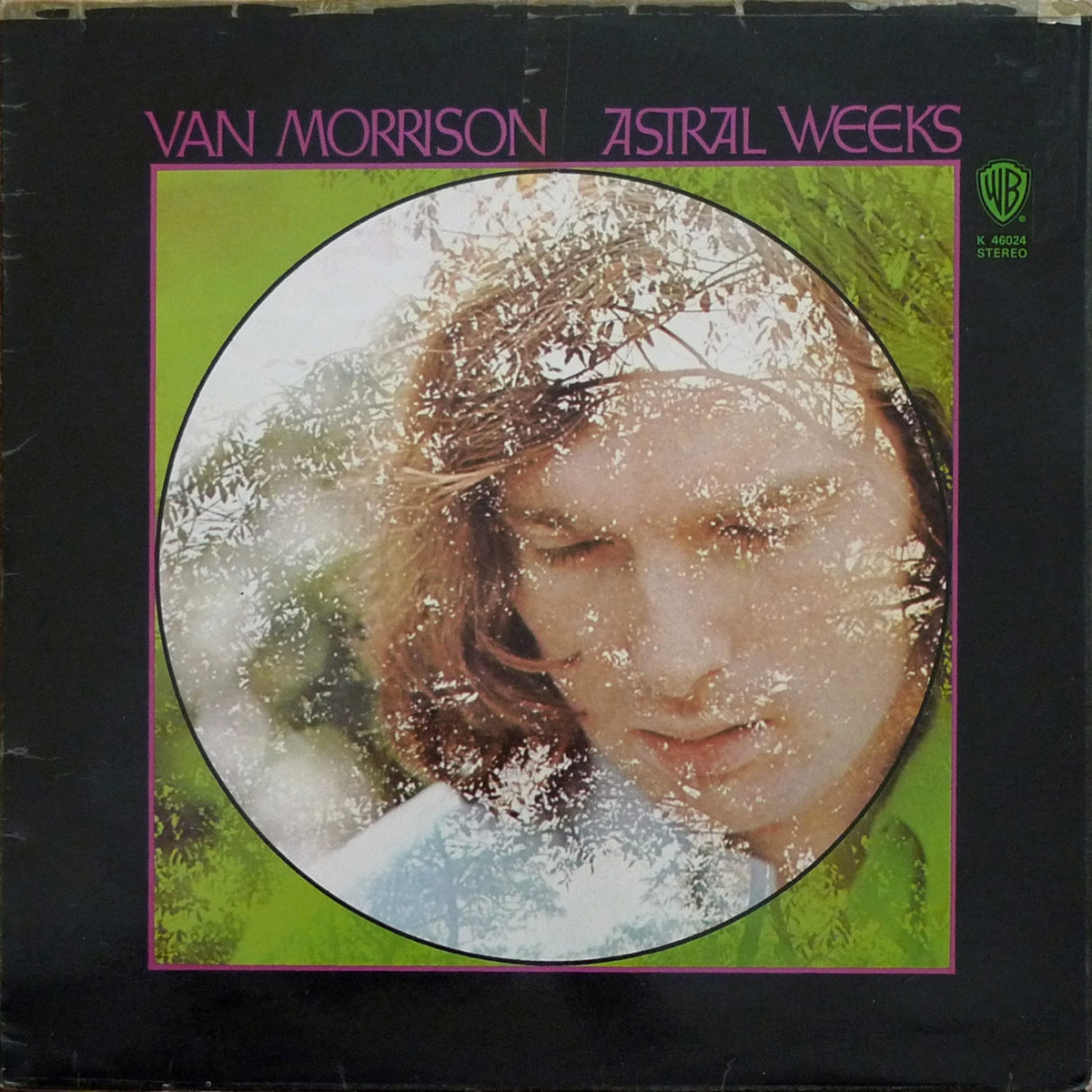

Astral Weeks Cover by John Keogh on Flickr

One day in 1968, when John Sheldon was 17 years old, a short, dough-faced man in a button-down shirt showed up on the doorstep of his parents’ house in Cambridge. It was the Irish songwriter for whom Sheldon, a guitar prodigy, had recently auditioned. Now here the guy was on his porch, all 5-foot-5 of him, with an upright bass player looming over his shoulder.

“I didn’t really know quite what to make of him,” Sheldon remembers. “He didn’t say very much, he had no social, kind of, ‘How you doing?’ There wasn’t any of that. We played for a while, and the first thing I remember him saying was, ‘Are you available for gigs?’”

And so it was that John Sheldon became, briefly, the guitarist for Van Morrison.

Morrison was riding the success of his first single, “Brown Eyed Girl,” but he hadn’t yet become a household name. And Boston wasn’t rolling out any red carpets upon his arrival. “There was a gig at the Boston Tea Party,” Sheldon says, “but we had no drummer. I remember going out in a car with Tom [Kielbania, the bass player] and Van. We drove by Berklee [College of Music] and saw this guy on the sidewalk. Tom said, ‘Hey, it’s Joe. Joe, do you want to play drums?’ This is the kind of level that things were happening at then.”

Morrison quickly became a constant presence in the Sheldon household. He would tie up the family phone, carrying on epic arguments over the royalties for “Brown Eyed Girl.” “My parents would come in for breakfast on Sunday,” Sheldon recalls, “and it would be a bunch of people they didn’t know.” One day, Sheldon says, “Van came over to the house in Cambridge and he said that he had a dream and in the dream there were no more electric instruments. So he got rid of the drummer and rehearsed with just me and Tom. Tom played a standup bass, me on the acoustic guitar. So that’s when we started playing songs like ‘Madame George.’”

After a few weeks, the trio went to meet a producer named Lewis Merenstein at Ace Recording Studios, across from Boston Common. At the time it was one of the few professional studios in Boston, the place where the original “Charlie on the MTA” had been recorded.

Thirty seconds in, “my whole being was vibrating,” Merenstein said in 2008. “I knew he was being reborn…I knew I wanted to work with him at that moment.”

Sheldon remembers the producer telling Morrison, “I think you’re a genius, and I want you to make a record for Warner Brothers.” It was clear to Sheldon that Merenstein wasn’t talking to any of the other band members.

The song Van Morrison played that day, the one that so unhinged the producer, was called “Astral Weeks,” and it would become the title track on the album that would redefine Morrison’s career. That audition of sorts at Ace was the last moment Sheldon was involved in the recording. His hunch had been correct: When Morrison left to record Astral Weeks in New York, he didn’t take Sheldon with him.

These days, when he looks back, what Sheldon remembers best from that summer is Morrison sitting in the yard of his parents’ house in Cambridge, playing those songs from Astral Weeks. “It’s sort of a shining memory, I’d guess you’d say. He’s out in the sun, he’s playing those songs, and they’re very melancholy. They’re mournful songs. Years later, maybe 10 years later, a friend of mine got me stoned and put on Astral Weeks, and I went, ‘Hey, man, this is good.’”

Astral Weeks is widely regarded as one of the best albums in the rock ’n’ roll canon. Martin Scorsese claims the first 15 minutes of Taxi Driver are based on it. Philip Seymour Hoffman quoted it in his Oscar acceptance speech. Elvis Costello called it “the most adventurous record made in the rock medium.” Legendary music critic Lester Bangs declared it the most significant record in his life, a “mystical document.”

It is also an album that was planned, shaped, and rehearsed here, in and around Boston and Cambridge. This fact has been a sort of secret kept in plain view. After all, the first clue is printed right there on the back of the album sleeve:

I saw you coming from the Cape, way from Hyannis Port all the way,

When I got back it was like a dream come true.

I saw you coming from Cambridgeport with my poetry and jazz,

Knew you had the blues, saw you coming from across the river…

Morrison has claimed, preposterously, that he wrote this poem years before ever coming to Massachusetts. In the intervening years, it’s almost been as if he were covering his tracks. The city, for its part, hasn’t done much to claim the album as its own. When I first heard that Morrison composed Astral Weeks here, the information was disorienting: It didn’t make any sense. Why wasn’t this a bigger part of Boston’s well-groomed rock folklore—right up there with, say, the fact that Bob Dylan workshopped songs at Club 47, in Harvard Square? Hell, why was Morrison even in Boston in the summer of 1968?

The last question, it turns out, is the easiest to answer—and one of the most outrageous rock ’n’ roll tales ever told. Astral Weeks was born out of sheer desperation, conceived at a time when Morrison was trapped in the world’s worst recording contract and evading record-industry thugs.

Just a few years before, Morrison had been aimless in Belfast after dissolving his affiliation with his band, Them. He was offered a recording contract by an American music producer named Bert Berns, a man described by his own biographer, Joel Selvin, as reeking of “Pall Malls, cheap cologne, and hit records.” Berns was a hitmaker; he wrote “Twist and Shout,” and Them had recorded his song “Here Comes the Night.” Morrison barely read the contract before signing it. That’s how he wound up in New York, living with his girlfriend, Janet Rigsbee, in a series of cheap hotels while he worked on tracks for Berns’s label, Bang Records.

But things between Berns and Morrison soon soured. At 22, Morrison thought of himself as a singing Irish poet. Berns, meanwhile, wanted to ride the late-’60s wave of psychedelia, and he released Morrison’s debut solo album under the title Blowin’ Your Mind!—with a cover sporting trippy fonts and patterns, and a photograph of a visibly sweaty Morrison, clearly meant to convey that the drugs had just kicked in.

Morrison was furious. It was a cheap marketing ploy meant to sell him as something he decidedly was not. Worse, he was still broke, even though “Brown Eyed Girl” was a huge success. Morrison and Berns argued constantly over royalties. Then, on December 30, 1967, Berns—his heart weakened by childhood rheumatic fever—died of a heart attack at just 38 years old.

It turned out Bang Records had some unsavory connections, and now that Berns was dead, Morrison’s main contact at the label was Carmine “Wassel” DeNoia, whose father was the inspiration for the character Nicely-Nicely in Guys and Dolls. Wassel was an even less forgiving boss than Berns. Legend has it he once threw Tiny Tim off a boat because he didn’t like the look of him.

Even today, Wassel hasn’t lost any of his tough-guy shtick. “Hello, City Morgue” is how he answered his phone one night last October when I decided to ring him up. He was friendly, forthcoming, and a little scattered, but readily agreed to meet in person to talk about Van Morrison. “I helped that guy out,” Wassel insisted. “If he ever sees me again, he better stand up and salute me!”

Wassel lives in a Manhattan building called the Franconia, on West 72nd Street. When I arrived, he was wearing a loose white undershirt and blue pajama pants. His thick-rimmed black glasses were giant windowpanes that framed his eyes. “Didn’t I meet you once before?” he asked me. He said he’d been living at the Franconia for 56 years.

Wassel told me he “got Bert Berns started in the music business.” Of course, Berns had been involved in the music business long before he met Wassel, so what he actually meant was that he introduced Berns to full-blown gangsters like Genovese family member Patsy Pagano—and to the quick results that brute force yielded when applied to the creative industries. Back in Berns’s day, this included everything from bullying performers back into studios, dismantling local record-bootlegging operations with a sledgehammer, and finding ways to borrow money that didn’t require a credit check. In the unpredictable world of the record business, these connections gave Berns and Bang Records an advantage that could level the playing field with bigger and more-established labels.

In August 1967, Berns organized a belated record-release party for “Brown Eyed Girl” on a boat that departed from 50th Street in Manhattan. Morrison attended with Janet. There’s a picture from this evening hanging on Wassel’s wall. The framed photo shows Morrison sporting a rare smile. Janet looks pleasantly taken aback by all the fanfare, Berns is glancing over at Janet, and Wassel is in back, a giant cigar stuffed in his mouth, his eyes closed, head tilted back.

I asked Wassel to tell me more about what happened with Van Morrison right before Morrison fled New York. For a moment he looked stumped. “Oh,” Wassel suddenly remembered, “I broke his guitar on his head.”

This is true. Here’s what happened.

One night, Wassel visited Morrison at the King Edward Hotel, where Morrison and Janet were staying. They were already anxious: Morrison’s papers were not wholly in order, and he was worried he’d be deported. Also, Morrison was severely intoxicated. Wassel asked about a radio he had given Morrison, which now appeared to be broken. Morrison’s temper flared up, worsened by the booze, and Wassel put an end to his incomprehensible Gaelic swearing by smashing Morrison’s Martin acoustic guitar over his head.

All of this may have had something to do with why, in early 1968, Morrison and Janet hastily married and moved to Cambridge.

“My band then was called the Hallucinations,” Peter Wolf tells me over bourbon and pastries at his home in downtown Boston. “A kind of neo-punk thing. We practiced at the Boston Tea Party, on Lansdowne Street. One day during rehearsal, this guy came into the club asking for the manager. He was looking for a gig. He was speaking real funny.”

When Morrison arrived in Boston in 1968, few people were more dialed in to the rock counterculture than Wolf. Not long after, Wolf would make Boston rock history as the frontman of the J. Geils Band, but back then he still had his overnight shift DJing at the legendary rock station WBCN, where he’d take on a persona he called the Woofa Goofa, a hyperfast, stream-of-consciousness combination of total jive and rock ’n’ roll minutiae. “At the time, Them’s ‘Gloria’ was like the national anthem for every garage band in the country. Of course I knew him,” Wolf says. But even for an established musician like Morrison, “the gigs and opportunities in Boston weren’t coming easy.”