Frederick Douglass Exhibit Opening at the Museum of African American History

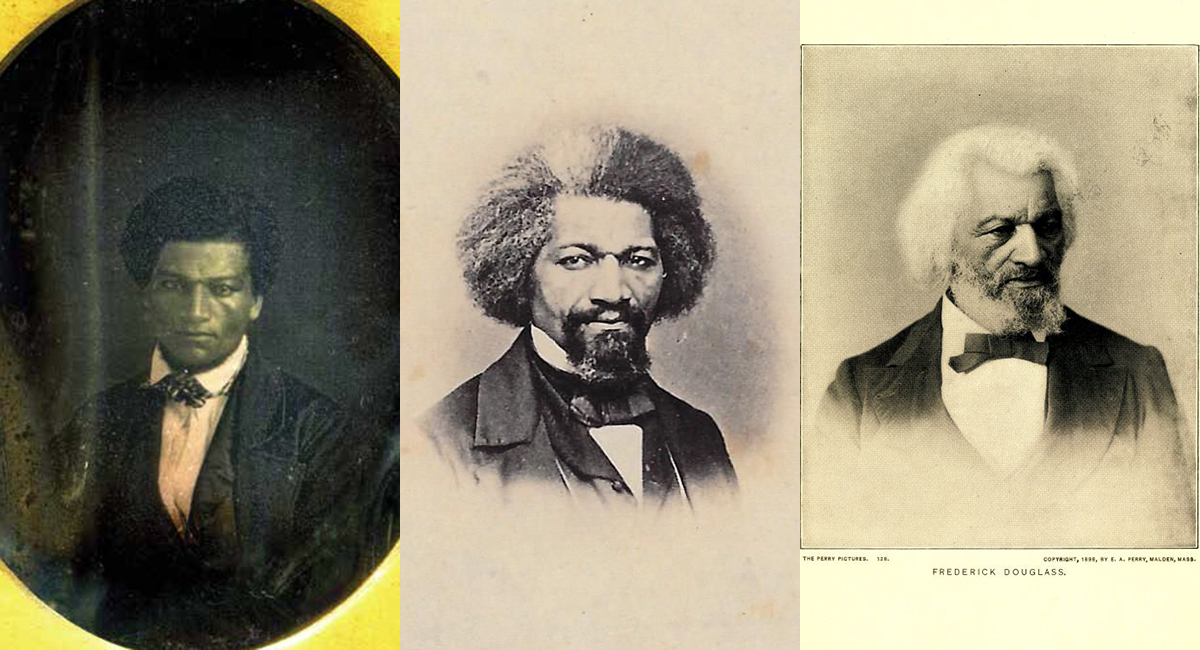

Left and center: courtesy of the collection of Greg French / Right: courtesy of the Museum of African American History

One man, countless images. Starting July 15, the Museum of African American History welcomes many Frederick Douglasses to its walls for a new exhibit, “Picturing Frederick Douglass.” Most know of Douglass as a fervid abolitionist, but—fun fact alert—he was also the most photographed man of the 19th century, with his 160 preserved images trumping Abraham Lincoln’s 126.

L’Merchie Frazier, Director of Interpretation and Education at the Museum of African American History, shares her excitement that the museum will be able to exhibit these images to show Frederick Douglass in a new light. “One of the anchor icons in the museum collection is abolitionist Frederick Douglass. He rose from an enslaved black man to an ambassador statesman and he reflects the African American experience of triumph,” Frazier says.

Douglass’s interest in photography has been largely overshadowed by his political stature. In fact, prior to the publication of Picturing Frederick Douglass, the book written by Zoe Trodd and John Stauffer that inspired this exhibit, most Douglass photographs were hidden. “We got to find Douglass in unexpected places, in archives that didn’t know they had him, photographs of Douglass thrown in boxes and labeled ‘unidentified negro,’” Zoe Trodd, co-author of the book and co-curator of exhibit, explained.

The search began with challenges. “When we went to meet them, they thought we were a little bit mad,” Trodd says of the archivists whose collections they searched. But the work has certainly paid off. Picturing Frederick Douglass, both the book and exhibit, shows the inextricable ties between Douglass’s politics and photography. The first documented photograph of him was taken in 1841, just years after he became free. In it, he confronts the camera with a direct, unsmiling stare—a much different image than happy slaves in black-face minstrelsy shows. “Throughout his life, he intentionally used the studio and his portraits as the foundational visual image to propel to the issue of ending slavery and promoting democracy and freedom,” Frazier says.

Trodd explains that most photographic manuals from the time actually recommended that the subject look above and beyond the camera. But Douglass stared directly into the lens, confronting the viewer with sad anger that resisted moral complacency. He used photography as a tool for social change built upon the power of his solemnly angry expression.

“Douglass was working really closely with photographers to achieve just the perfect shot. Because, for him, to be better-dressed, more photographed, more elegant, more dignified, more seen than the average white American, was to make an argument for African American’s humanity and their citizenship and their equality,” Trodd says. “For the first time in history, he’s trying to create a black public persona… He’s trying to give us an image of black leadership that is a precedent all the way through to King and onward to Obama.”

Paintings and other artistic adaptations of Douglass often forced a smile, softened his features, and lightened his skin to present, in Douglass’s words, “a much more kindly and amiable expression than is generally thought to characterize the face of a fugitive slave.” He heralded photography for its truth, honestly depicting what is in front of the camera, without need for smiles to make a black face palatable to a morally culpable and largely white audience.

“He rails against what he thinks white artists are doing when they represent African Americans. He thinks they exaggerate stereotypical black features, or he often finds that they try to whitewash black people,” Trodd says. “He’s pushing against not just the minstrelsy but also some of the abolitionist print culture, the whipped back and the bleeding hands, the imagery of exposure that was supposed to be helping with anti-slavery, but actually put African Americans in this position of being quite passive, victims.”

In essence, Douglass engaged in what Trodd calls “the first great battle in American visual culture…him on the one hand with his images of dignity and self-possession, and on the other hand racist and pro-slavery imagery and also paternalistic white abolitionist imagery.” And Douglass’s battle is by no means the last. “Today you see it every time someone is killed by the police and there’s a tension between the images that get circulated of them looking like ‘thugs’ and the images that their family sees as more accurate, where you realize how young a lot of these victims of police brutality are.” Trodd hopes that viewers will keep these connections in mind. “Abolitionism is a usable past for social justice movements,” she says.

Frazier echoes Trodd’s sentiments. She hopes viewers of the exhibit will think, “First of all, wow, Frederick Douglass. Second of all, the brilliance of using the tools of media that are generated by the time to advance a movement and develop policy that effects humanity, reflected in the advancement of the civil rights movement and the use of television as a strategy, and analogous also to campaigns like Black Lives Matter and cell phone photographs on social media.”

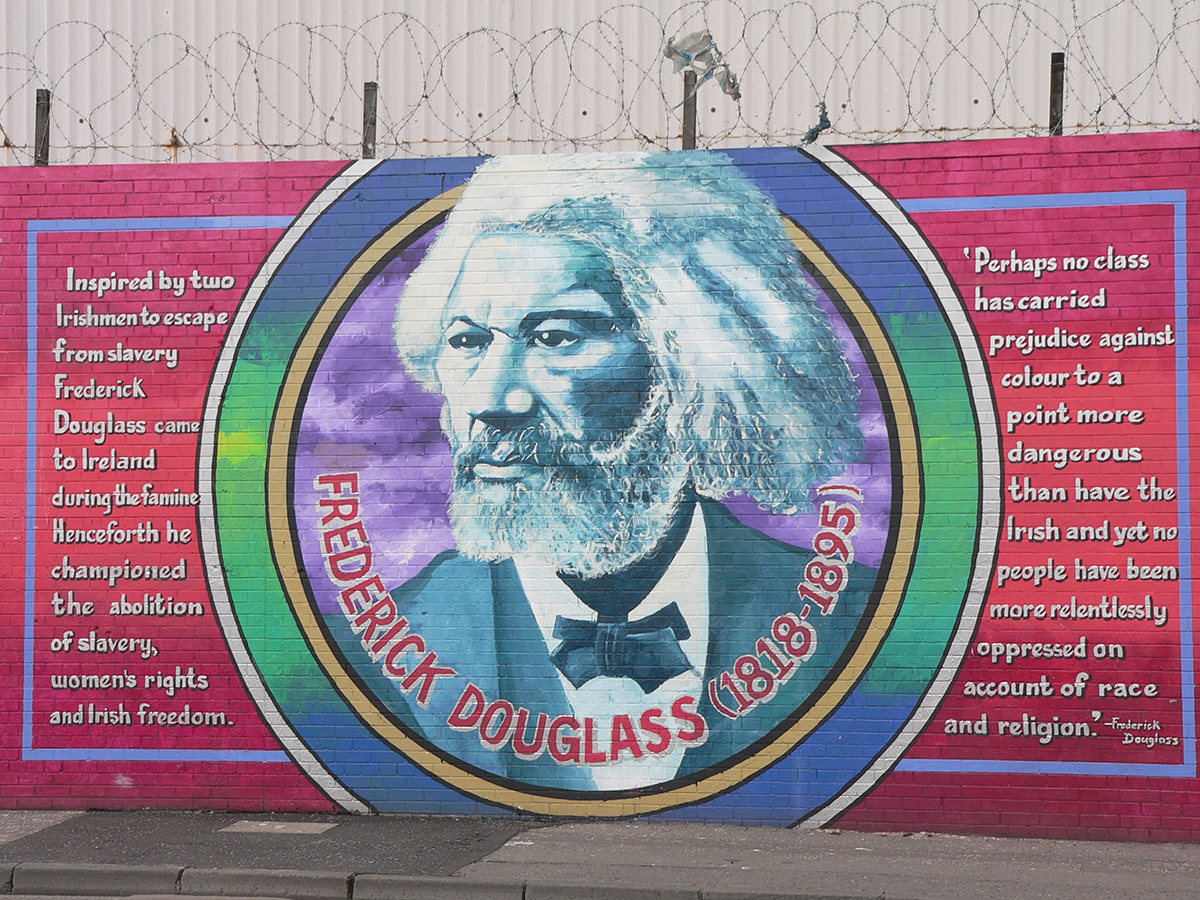

Mural of Frederick Douglass in Northern Ireland. / Mural on the ‘Solidarity Wall’ by Laurence’s Travels on Flickr/Creative Commons

Douglass’s influence is not limited to national police brutality. The Frederick Douglass Family Initiative works closely with a global movement that fights the enslavement of 46 million people. Trodd shares that Douglass is also the figure depicted most frequently in murals, with locations in the US and internationally.

However, more intimate moments hide among Douglass’s image of black leadership and power. For example, the exhibit will feature a never-before-seen photograph of Douglass with his youngest daughter, Annie—the only photograph of Douglass with one of his children. Annie is five in the image; she died four years later. “To see his arm around her in the photograph, we get to see Douglass the father,” Trodd says. “To realize she died just a few years later—it was really moving actually.”

Still, much remains hidden. Frazier brings up his sometimes complicated relationship with John Brown. “Our question becomes, how much do you really know about Frederick Douglass?”

$5, July 15, 2016-July 31, 2017, Museum of African American History, 46 Joy St., Boston, afroammuseum.org.