This Is What Poison Ivy Looks Like

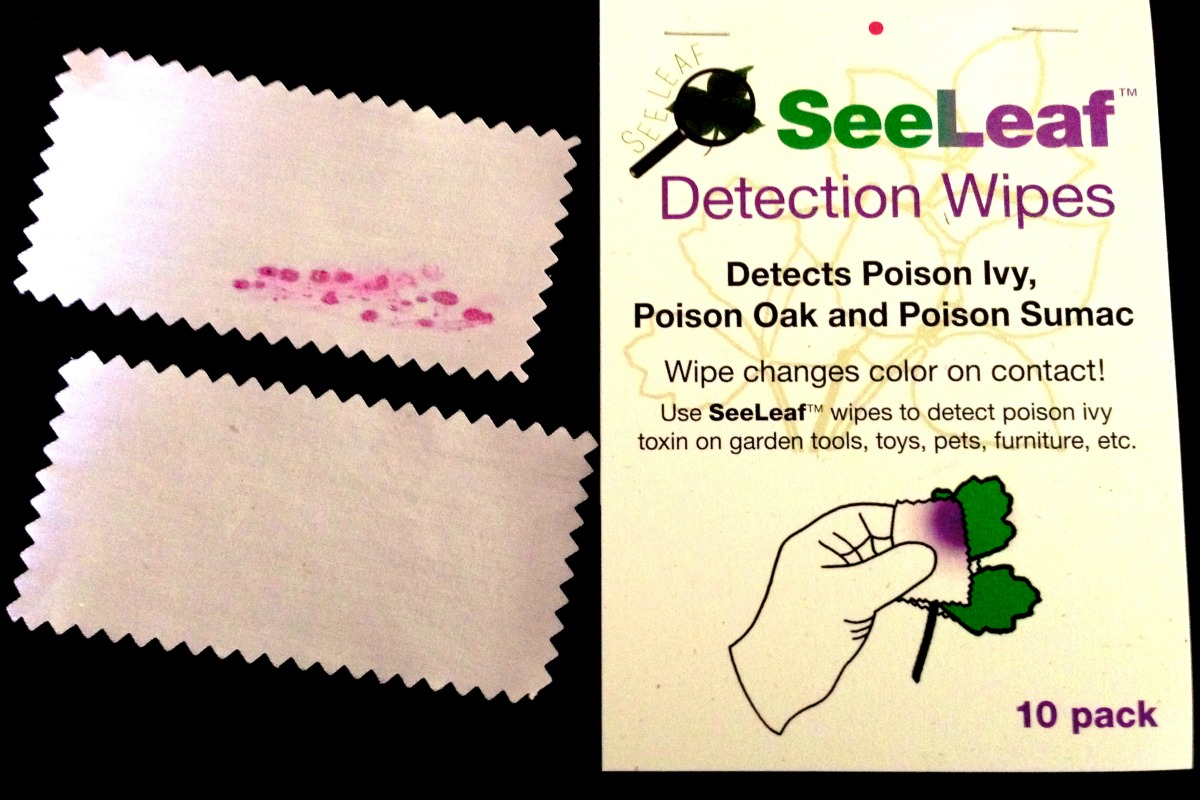

Seeleaf’s before and after.

Larry Brown already knew the product he co-created could detect poison ivy, but he wanted to know if it could also detect poison oak and poison sumac. “You get the same rash from them all,” he says.

The search for poison sumac led Brown to the Arnold Arboretum’s website which fortunately said that yes, in fact, there was a poison sumac bush there, but, alas, no direct map on where to find it. “There’s a map that gives you directions in 100 foot grids,” Brown said. “I went to the Arboretum hoping [the bush] was labeled so I could find it, but it wasn’t. I had to go bush to bush testing our product on each bush in a 100 foot square. Then, bingo, I found it! It was a great for our patent application.”

The patent application is for Seeleaf, a Newton-based startup created by Brown, who is the president, Bob Feeney, a chemist and vice president, and Business Manager Jeremy Jaffe. Seeleaf is detection cloths that turn purple when they come in contact with the rash causing poison in poison ivy, oak, and sumac plants. The wipes, which were just made available for purchase a few weeks ago, are $15.95 for a 10-pack, and $9.95 for a 5-pack. The cloths can only be used until the poison is detected, and then must be discarded.

Feeney remembers his poison ivy experience well. It was the dead of winter, and he was at a Christmas tree cutting party in New Jersey where he apparently came in contact with poison ivy on the trunk of one of the trees. “I did not know you could get poison ivy in the wintertime,” he says. “I mean, the vine was dead. A day or so later I developed poison ivy on my wrist, and every time I put my coat on, I was getting it again. Every few days I kept reinfecting myself. I went to a doctor and he said that I had poison ivy. Even though the leaves are dead, it can give you a rash for five years, the roots, the vines, the stems.”

That’s when Feeney, a chemist, began experimenting in his basement lab. He went through what he says is “a long series of experiments” that looked at different dyes that change from colorless to colored under certain conditions. When he found the dye with the right molecular chemistry to change color when in contact with poison ivy, he new that he stumbled upon something significant. Now, it was a matter of making it a practical application.

Brown and Feeney started by placing the dye on sticky tape and headed out into the woods. The dye, when in contact with poison ivy, oak, or sumac, turns a deep red/purple color. When the sticky tape method was perfected, the two knew that they had to get it on something more convenient for a consumer. That’s when Brown took it to his own basement lab.

“I have a lab in my basement, and basically, I was able to develop the process. We couldn’t dissolve it or classically put it into a medium to use to test poison ivy presence. The original method was to take the dye on sticky tape,” Brown, who is also a trained biochemist, says. “I researched how to put dye into a cotton fabric. Now, you just rub the leaf or break a stem right on the fabric and it helps determine whether or not the plant or stem is poison ivy. It’s an instantaneous reaction.”

“Nobody knows what poison ivy looks like without leaves,” Feeney says, “and it can also look different everywhere. What poison ivy looks like on the beach doesn’t look like what it does in the salt marshes in Scituate. It looks different in Newton than it does on the beach.”

What does poison ivy really look like?

On sunny, warm day in late-spring in North Easton, Mass., my elementary school class was taking its annual field trip to Sheep Pasture, a beautiful, educational farm near town. It was supposed to be a fun exercise; the students and parent volunteers all got a lesson on what poison ivy looks like before we were to go and explore the trees. We (the students) were blindfolded and taken into the woods where we were to touch and smell the different trees to try and identify the timbers without the benefit of sight. Parents were warned not take students to trees covered in poison ivy. That is, assuming they knew what it looked like.

I felt the trunk with my hands, rubbed the leaves against my face, and pressed my nose to the bark, when all of a sudden I heard a loud shriek. An employee saw me, blindfolded, all up on this tree that was covered in poison ivy.

Let’s just say I’ve avoided the vine like the plague for the last 25 years. Yet, to this day, even after doing 100 Google searches, it’s still so hard to really know what the heck poison ivy looks like because every bush looks like poison ivy. You’d think that by avoiding the woods, you’re okay, but in reality it’s at the beach, on city sidewalks, in yards, and even possibly on your fence.

Below, images of poison ivy growing around Massachusetts.

Wait, that's poison ivy?