Can KJ Seung Change How the World Treats Tuberculosis?

Medical supplies from the Eugene Bell Foundation are prepared for delivery. / Photograph courtesy of KJ Seung

I first met Seung about three years ago. At the time, I was an editor at Partners in Health, the Boston-based nonprofit where Seung has spent nearly his entire career. I was not part of Seung’s team, but our work overlapped on occasion.

Fit, with thick black hair accented by a streak of gray, Seung can make a budget suit from T.J. Maxx look like it came custom from Hermès. The 45-year-old doctor possesses the type of dark humor you need when your chosen line of work is fighting a disease that kills more than 1 million people a year, and whether he’s training a young Nigerian physician to manage the complex side effects of TB drugs or reviewing a grant proposal, Seung demands precision and perfection. Among his more-provocative pieces of attire is a tan blazer with the word “Arrogant” embroidered in pink stitching down the sleeve. He sometimes attempts a kind of self-deprecating stance, but those who work under him know better: Seung has a high opinion of himself, and he can be an inspiring or demoralizing presence, depending on the day. That stubbornness, however, has been an asset to Seung in his battle against the healthcare establishment’s conventional thinking.

Back in the 1990s, before he knew anything about TB, Seung was, by his own admission, “a very bad medical student” at Stanford. That was surprising; Seung was a Harvard grad, born into an intensely successful family. His father, who emigrated from North Korea as a young man, is a renowned philosopher at the University of Texas at Austin. His mother is a classically trained pianist who studied at Juilliard. His older brother Sebastian is a famous neuroscientist and Princeton professor whose TED talk has been viewed more than 800,000 times.

Years later, when it came time to select his residency program, Seung opted for a county hospital in Los Angeles. He soon found himself walking the line between doctor and advocate. Budgets were tight, resources were limited, and many of the patients didn’t have insurance or access to healthcare. Seung recalls insisting that every patient deserved the highest level of care—a view that he claims administrators didn’t always share. “You constantly [felt] like you were fighting the system,” he says of his time in Los Angeles. “I think those lessons were perfect for my current work.”

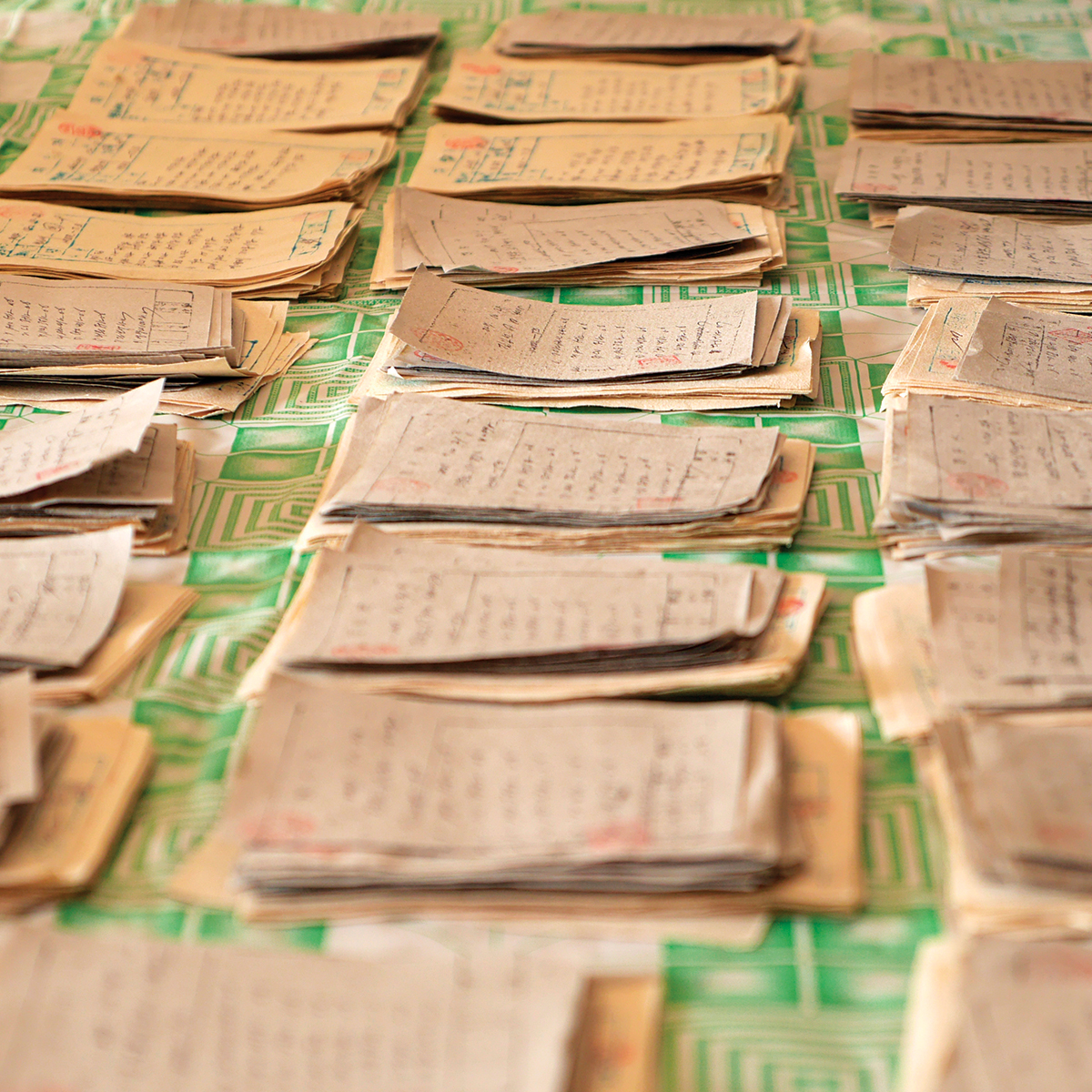

Stacks of patients’ medical prescriptions. / Photo courtesy of KJ Seung

In 2001, after completing his residency, Seung joined Partners in Health, recognized for its social-justice approach to global healthcare. Its physicians were known for training locals and building functioning health systems in places beset by dysfunctional governments and meddling foreign aid agencies. One key focus for Partners in Health became fighting drug-resistant TB, particularly in countries that hadn’t acknowledged the presence of the disease. In its early days, those efforts were so successful that the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation awarded it $44.7 million to expand them.

When he was 31 years old, Seung first signed on to fight tuberculosis in Carabayllo, a shantytown near Lima, Peru. The slum marked an inflection point in the history of drug-resistant TB. Before Seung arrived, two of PIH’s founders, doctors Paul Farmer and Jim Kim, had spent years in Lima, expressly challenging the WHO’s insistence that drug-resistant TB was too expensive to treat in poor countries. Ironically, the WHO had been touting Peru as a success story for its standard four-drug regimen. But the more time Farmer and Kim’s team spent in the slums of Lima, the more cases of drug-resistant TB they uncovered. To treat patients, they built a system that screened for drug resistance and delivered the correct drugs, then hired nearby community members to accompany patients through the long and difficult treatment. Farmer and Kim were having remarkable success—curing 80 percent of patients they treated. But they were reaching only a tiny portion of Peruvians stricken with drug-resistant strains.

Seung’s mentors had prepared him for the challenge of battling what he calls “shockingly crappy public health policy,” but nothing could have prepared him for the social complexity of the disease. He spent months working with Peruvian nurses and doctors, building on the gains his mentors had made. Though he had studied the clinical aspects of TB, it was the first time he’d come face to face with a full-blown multidrug-resistant TB outbreak in a country ravaged by poverty. It was emotionally grueling work: Seung and the local nurses made rounds along the steep dirt roads of Carabayllo, going shack to shack, meeting with very ill patients. In many households, family members had accidentally infected their loved ones, and were hopelessly watching their siblings, parents, or children die.

After nearly three years of shuttling back and forth between Peru and Boston, Seung was exhausted and depressed. He was saving lives, but death still weighed heavy on him. There were too many patients he was unable to help. Burnt out, Seung threw in the towel and took a job in 2004 at the WHO. The organization’s policies had infuriated him, but he thought he could change the system from within: He wanted the WHO to train local healthcare workers in poor communities to administer AIDS medication. His stint with the agency didn’t last long. Soon after arriving at the WHO’s headquarters in Geneva, terrifying news emerged from South Africa: Doctors had detected a new strain of tuberculosis that was resistant not only to the key first-line medications endorsed by the WHO, but also to some of the most effective second-line drugs used to treat multidrug-resistant TB. According to one of the first official medical reports, this strain was killing 98 percent of patients—and, uncharacteristically for TB, it was doing so at breakneck speed. The median time before death was a mere 16 days. It became known as extensively drug-resistant TB, or XDR-TB, and it scared the hell out of everyone.

In 2006, Seung quit the WHO and returned to Partners in Health. His first task was to help build a drug-resistant TB program in Lesotho, a small and deeply impoverished enclave-country nestled inside South Africa. The average life expectancy was 45, and nearly a quarter of adults had HIV. The “noxious synergy” of drug-resistant TB and AIDS floored Seung. He was used to seeing TB patients die over the course of months or years; here they were dying in weeks. Overwhelmed, Seung called his mentor, Paul Farmer. “It’s not going to be like Peru,” he told Farmer. “Are you going to be happy with a 50 percent cure rate, with half the people dying?”

This was the fight Seung had chosen: a fight that could not be won, that could only be lost more slowly. The plan was the same: train local nurses and doctors, dive into the remote communities to screen as many people as possible, and hunker down for the long defeat. It was awful, and progress came haltingly. The cure rate eventually ticked up to around 70 percent, where Seung says it hovers today. The outcomes are consistently better than the global average, but drug-resistant TB remains difficult to cure.