What Are the Chances?

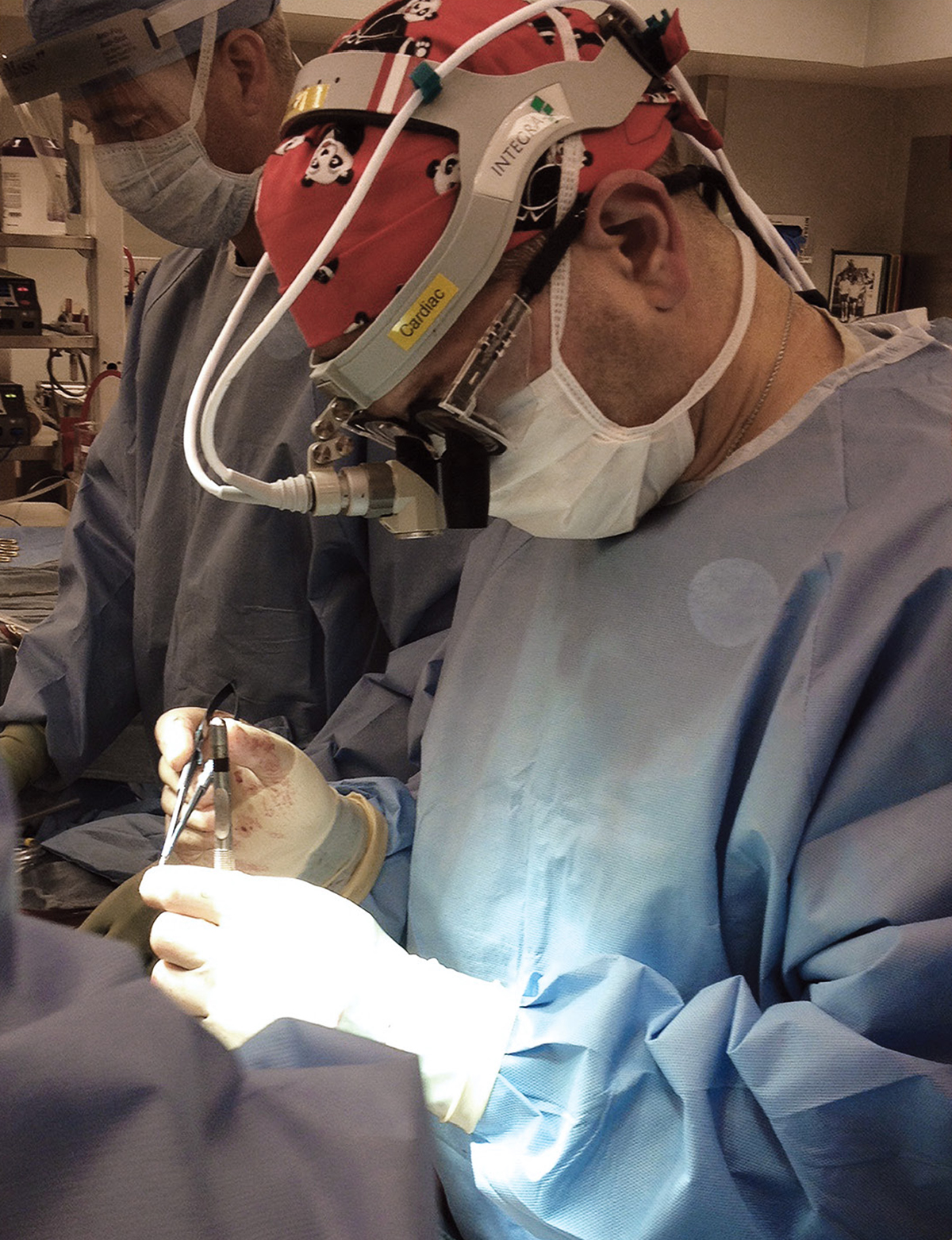

Hooman Noorchashm worked as a cardiothoracic surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital when his wife was diagnosed. / Photograph courtesy of Hooman Noorchashm

Amy was educated by nuns—the sisters of St. Casimir—at Villa Joseph Marie, a tiny Catholic girls’ school in Bucks County. She came from a big family—her parents, who divorced and then both remarried, numbered eight kids between them—and she always wanted a big family of her own. She went to Penn State after high school, then to grad school at Penn.

What she won’t tell you, her husband says, is the rest of the story: that she was valedictorian at Villa Joseph Marie, that at Penn State she was Phi Beta Kappa, Golden Key, and dean’s list. That when, after getting her PhD in immunology, she decided to apply to med school, she got into every one she applied to except Cornell and Harvard. That by the time she graduated from Penn Med, she had three kids. She carried two of them, Joseph and Nadia, onto the stage to accept her diploma. She got a standing ovation from the crowd.

Hooman first saw her shortly after she started at Penn, in 1995. They were both going after their doctorates then. “I noticed her walking down the hall with a lab bucket,” Hooman says. “I was star-struck. That was that.” In their kitchen, he smiles, waves a hand toward her, then himself. “We’re basically a testament to my persistence,” he tells me.

“Pretty much,” she agrees.

Besides the fact that they’re both doctors and have six kids, they’re like any couple you know. He’s compact but strong, with forearms that remind you how physical surgery can be. She’s wavy-haired and pretty, though she sometimes looks tired. “We’re in sync in a lot of ways—we both wanted a big family, we’re strong on social service—but in other ways we’re diametrically opposed,” Amy says. “He likes to read autobiographies.”

“She likes Stephen King,” Hooman says.

“I do like Stephen King. I like medical fiction, historical fiction.”

“She reads a lot about influenza epidemics,” Hooman says, and laughs. In a discussion of why they chose the medical specialties they did, he’s the one who points out that Amy is dual-board-certified, in critical care and anesthesiology.

“Being in the intensive care unit is just like being at home,” Amy says. “There’s always a clamor, only they’re not saying, ‘Mom!’”

They’d been living in Narberth, on Philadelphia’s Main Line, for 10 years when Hooman got his fellowship at Brigham and Amy landed her job at Harvard. She wasn’t sure about moving. In Boston, they’d be isolated. She’d have to start all over again with church, community, friends. But they found a similar town in Needham. They found a great house, serendipitously, though it needed work. (“There was only one bathroom,” Amy says.) They found a school for the kids. They made more friends. They had Ryan. And Amy had that operation to make her right again.

When you train to be a cardiac surgeon, Amy mentions, they teach you to walk into a room where a patient is waiting and say, “I need to cut into you right now.” There isn’t any space for self-questioning or doubt. You know that old joke about how God sometimes thinks he’s a doctor? Becoming a heart surgeon does that to you.

So it really shouldn’t have surprised anybody at Brigham and Women’s when Hooman, as he sat in the airport waiting to fly back to Boston from Duke, did a Google search for “morcellation.” He learned how to spell it. He learned that doctors performed 100,000 to 200,000 operations like the one on his wife each year. “So I’m thinking,” he says, “even if it is one in 10,000, that’s still 10 or 20 women” with sarcomas that were spread.

So he did more research. He came across a paper that had been published in November 2012, about a year before Amy first went to Michael Muto. “Peritoneal Dissemination Complicating Morcellation,” it was called. “Guess who was one of the authors?” he asks me. “Dr. Muto. The research had been done at Brigham. With morcellation! By Dr. Muto.” His voice gets increasingly high. “He’s telling me one in 10,000,” Hooman says, but the Brigham doctors found unexpected sarcomas in 10 out of 1,091 samples of tissue from women who’d undergone uterine morcellation—suggesting, the paper said, an “apparent associated increase in mortality much higher than appreciated currently.” That, Hooman says, is when he started to get “a little bit upset.”

And Penn and Harvard and Brigham and Women’s had all trained Hooman to be cool, unafraid, to walk into rooms and tell strangers the last thing they wanted to hear. “They made him this way,” Amy says with a shrug.