The Briefcase

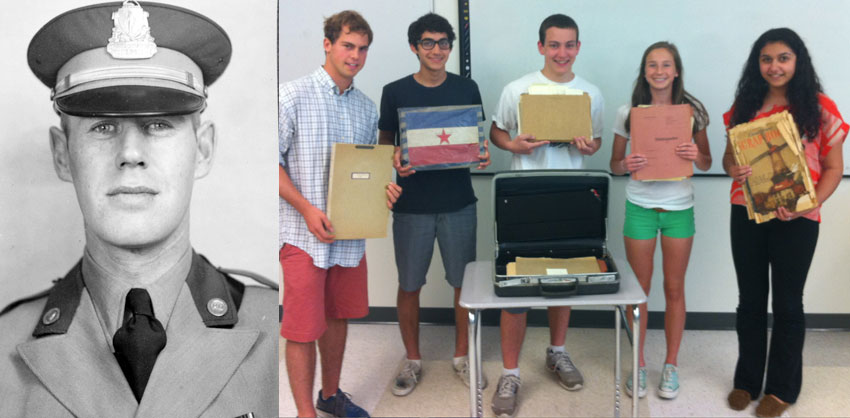

Left: Martin Joyce. Right: Members of the Wayland High School history class displaying Joyce’s materials. (Courtesy of the Wayland High School History Project)

Kevin Delaney had seen the old, gray briefcase in the Wayland High School history department’s storage room before. The case, one of those sturdy plastic Samsonite types from the ’70s, had been around so long, neither Delaney nor any of his colleagues knew how it had arrived there.

It was the spring of 2011, and Wayland High was preparing to relocate to a newly constructed facility. It fell to Delaney, Wayland’s history chair, to decide which of his department’s materials would make the move. And so he unfastened the lid and began to page through the yellowing papers contained inside.

“I had actually seen it before and given it a peek, and I knew there was something intriguing. But I’d never dumped the contents out and given it a scrub down,” Delaney remembers. “So I put them on the table, started to pore through them, and didn’t take long to figure out that they were all linked.”

Inside were the assorted papers—letters, military records, photos—left behind by a man named Martin W. Joyce, a long-since deceased West Roxbury resident who began his military career as an infantryman in World War I and ended it as commanding officer of the liberated Dachau concentration camp. Delaney could have contacted a university or a librarian and handed the trove of primary sources over to a researcher skilled in sorting through this kind of thing. Instead, he applied for a grant, and asked an archivist to come teach his students how to handle fragile historical materials. Then, for the next two years, he and his 11th grade American history students read through the documents, organized and uploaded them to the web, and wrote the biography of a man whom history nearly forgot, but who nonetheless witnessed a great deal of it.

“Joyce became the thread that went through our general studies,” Delaney says. “When we were studying World War I, we did the traditional World War I lessons and readings. And then stopped the clocks and thought, ‘What’s going on with Joyce in this period?’”

As the class repeatedly asked and answered that question, they slowly uncovered the life of a man who not only oversaw the liberated Dachau but also found himself a participant in an uncommon number of consequential events throughout Massachusetts and U.S. history. In a way Delaney couldn’t have imagined when he first popped open the suitcase that day, Joyce would turn out to be something akin to Boston’s own Forrest Gump—a perfect set of eyes through which to visit America’s past.

The Early Years

For all Martin Joyce would eventually see, his childhood, in a small cape house on 21 Bertson Avenue in West Roxbury, seems to have been relatively uneventful. He shared the house with his parents and six siblings. An avid baseball fan, he likely followed Boston’s professional team through a busy two decades: as they changed their name from the Americans to the Red Sox, began playing in a newly constructed Fenway Park, and traded their best hitter to the upstart team in New York, plunging them into a dry period that would long outlast his life.

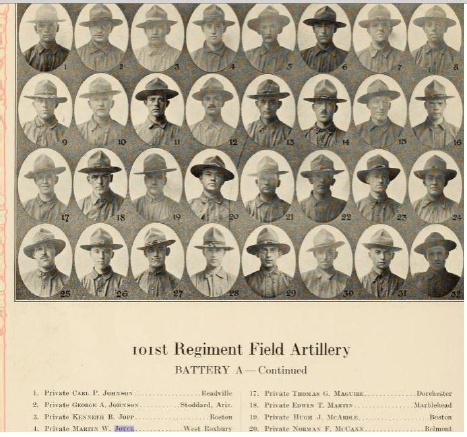

But young Joyce’s first real bout with a history came a few months after his 18th birthday when he was drafted into the U.S. Army’s 101st Field Artillery to serve in World War I, the conflict that had raged across the Atlantic for most of his high school years. Joyce left few personal reflections on the first of the two wars he would wage, but Delaney’s students traced his regiment and learned that he saw a fair number of pivotal battles. His military file shows that he was wounded in the Battle of the Argonne Forest, though not gravely, as he quickly returned to combat until the war’s end. After nearly two years abroad, he returned to Boston in April 1919, where throngs of Bostonians greeted his ship.

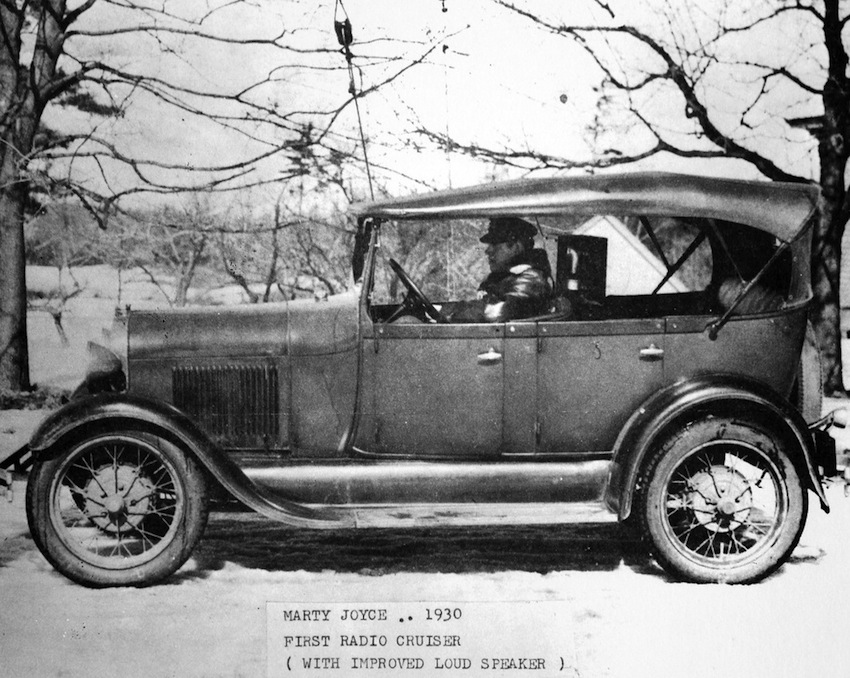

Joyce quickly recommenced his studies, obtaining several degrees and certifications for radio, then a cutting-edge technology. “Radio became a national obsession,” Delaney’s students wrote in their chapter of Joyce’s biography centering on the 1920s. For Joyce, it became something more: a professional vehicle. His expertise would dominate his working life, first with the Massachusetts State Police, and later with the U.S. Army’s Signal Corps, where it would afford him a chance to see the world and fuel a rise through the ranks that would eventually bring him to the gates of Dachau.

Delaney split the Wayland class into teams that first year, assigning each group with an era of Joyce’s life for which they were to write a chapter of his biography. For periods where his record was sparse, like World War I, this proved challenging, but by looking beyond the documents found in the briefcase, the students made a few breakthroughs.

Understanding Joyce’s life as a state trooper became easier, for instance, when one student, Matt Goddard, found the website for the Massachusetts State Police Museum and Learning Center in Grafton. He used it to get in touch with Tom McNulty, a retired statie and archivist who was more than willing to dig up and provide a collection of documents and photos, many concerning Joyce, as well as a perspective on life in the State Police during the 1920s and ‘30s. The kind of life the troopers lived in that era was, as it turns out, fairly all-encompassing.

“When you’re in the state police, you have to live in barracks. You don’t have a social life. They just kind of own you,” Delaney says. “It’s almost like you’re in the military.”

Joyce put his education to use, installing one of the first radios in a police car in Massachusetts. It was an innovation that vastly improved the department’s ability to respond to crimes. “Criminals fear the voice of WMP [the State Police dispatcher] more than they do a gun,” proclaimed a Boston Globe headline. Joyce’s duties extended to traditional police work, too, and his name pops up in local crime stories in newspaper archives throughout those years. One major issue we know he contended with firsthand was Prohibition. Another Globe article notes that Joyce was one of several officers who raided a Sudbury Barn that held a 2,000 gallon still. He and his colleague confiscated $50,000 of alcohol that night, roughly $700,000 in today’s dollars.

But by July 1941, war once again looked likely. And so, at the age of 42, Joyce was called to active duty with the U.S. Army’s Signal Corps, which manned the military’s communication systems. He took his leave from the state police and shipped off to Hawaii to install radar and other technologies in military bases and aircraft.

The Road to Dachau

With a new group of U.S. history students taking up the Joyce project in the second year, Delaney and his class gave Joyce’s files a closer read, looking for holes the first year’s class had left unfilled. As it turned out, Delaney and his students had left one major stone unturned. On December 7, 1941, they discovered, Joyce happened to be stationed at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, making him a surviving witness to the attack that would push the United States into war.

In fact, Joyce wasn’t merely witness to the disaster, but was tasked with an important duty the day of the attacks and for many months afterward. The military governor of Hawaii ordered the shortwave radios held by “enemy aliens” residing on the islands be confiscated, and Joyce was selected as the man to oversee the collection. From a New York Times report:

‘Baron Hee Hee’ as Hawaii has nicknamed the Tokyo radio propagandist, will lose his most appreciative audience here on Thursday when an order issued by the military governor takes effect barring the use of shortwave radio receivers by enemy aliens in Hawaii … Army Captain Martin W. Joyce, who will supervise the collection of banned radios, has his headquarters in the former Japanese Hotel in Honolulu.

As the attack plunged the Pacific theater into war, Joyce traveled to military bases throughout the region, from Noumeia to Fiji, installing equipment and checking on previous work. In 1944, he moved to the North African theater, where he jumped around from Saudi Arabia to India to South Africa to Egypt, doing much the same work he’d done in the Pacific. By the end of the war, Delaney’s class calculated, Joyce had traveled between 30,000 and 40,000 miles.

By 1945, the North African phase of war had ended, and the Allies had a new set of challenges. Joyce was summoned to London where he was ordered to take on a new role dealing with prisoners of war. Though he’d been a tech guy in the Army, his experience in law enforcement back home likely made him a good candidate for prison administration. Joyce was stationed at a prisoner of war camp in Algeria, and he quickly rose to the role of commander. From there, he moved between several different camps. At some point, he got a new order. As he writes in a document from the war years:

“During combat[,] information was received that the Dachau concentration camp was still in operation. I was attached to the 45th division which was committed to that Area and upon liberation of this camp, due to its size (32,500 political prisoners), ordered to take command. “

And so, Joyce departed for the continent.

‘32,000 Living Skeletons’

Dachau was a small town in the Bavarian region of Germany, near Munich when, in 1933, Heinrich Himmler set his sights on an unused ammunition factory there as a potential venue for a new prison. On March 22, 1933, the Nazis opened Dachau, their first concentration camp, primarily to hold political prisoners.

Initially, 200 men were transferred from a Munich prison. By the time it was liberated 12 years later, an estimated 35,000 to 43,000 prisoners had perished within its walls. The majority were political prisoners, but also Jews, homosexuals, dissenting priests, and other categories of “undesirables.” They came from all over; most were from Poland, but also Yugoslavia, Russia, Lithuania, and elsewhere. The Nazis subjected many of them to gruesome medical experiments. Many of the Dachau-related documents Joyce later put in a scrapbook concern the atrocities committed before his arrival. In one particularly gruesome account in Joyce’s papers, a Polish priest describes being injected with typhus taken from the sores of other prisoners and then observed for days as he begged for his leg to be amputated.

In the final days of Nazi control, it became clear that Dachau would be taken by the Allies. “Handing it over is out of the question,” Himmler ordered. “The camp is immediately to be evacuated. NO prisoner should fall into hands of the enemy ALIVE.” This commenced a furious, mostly failed attempt to remove prisoners and destroy evidence of the camp’s atrocities.

When the U.S. 7th Army did come upon the camp in April 1945, an iron gate welcomed them with a now-infamous inscription: Arbeit Macht Frei. Work makes you free.

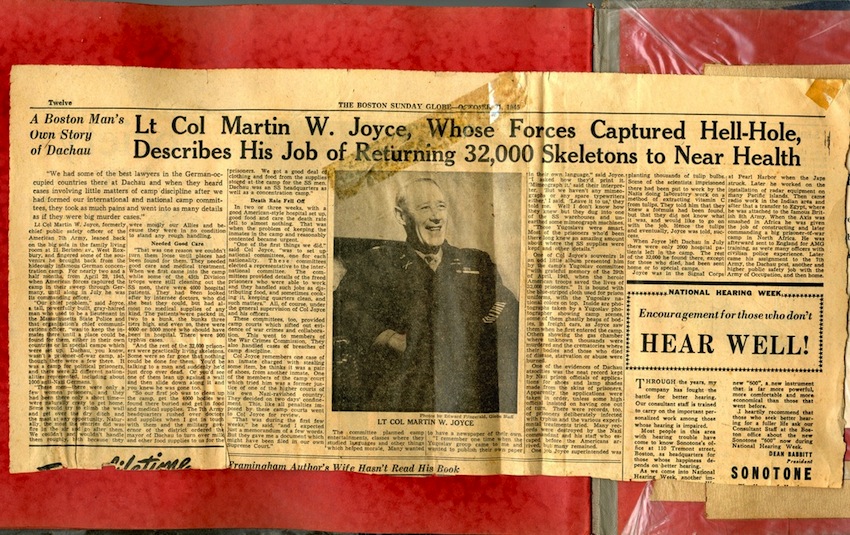

In October 1945, home from Dachau, Joyce sat for an interview with the Boston Globe. (Courtesy of LtColJoycePapers.org)

By now, Joyce had seen his fair share of history, but it was during these several months as C.O. that he would take a more prominent role in it. In a sit-down interview with the Globe upon his return, Joyce reflected on the atrocities he found when he first arrived. In addition to the masses of bodies, there were tens of thousands of hospital patients, thousands more that ought to have been hospital patients, and 900 suffering from typhus. He recalled in an interview:

And the rest of the 32,000 prisoners were practically living skeletons. Some were so far gone that nothing could be done for them. You’d be talking to a man and suddenly he’d just drop over dead. Or you’d see one of them lean up against a wall and then slide down along it and you knew he was gone too.

So our first job was to clean up the camp, get the 4,000 bodies we found there buried and get in food and medical supplies.

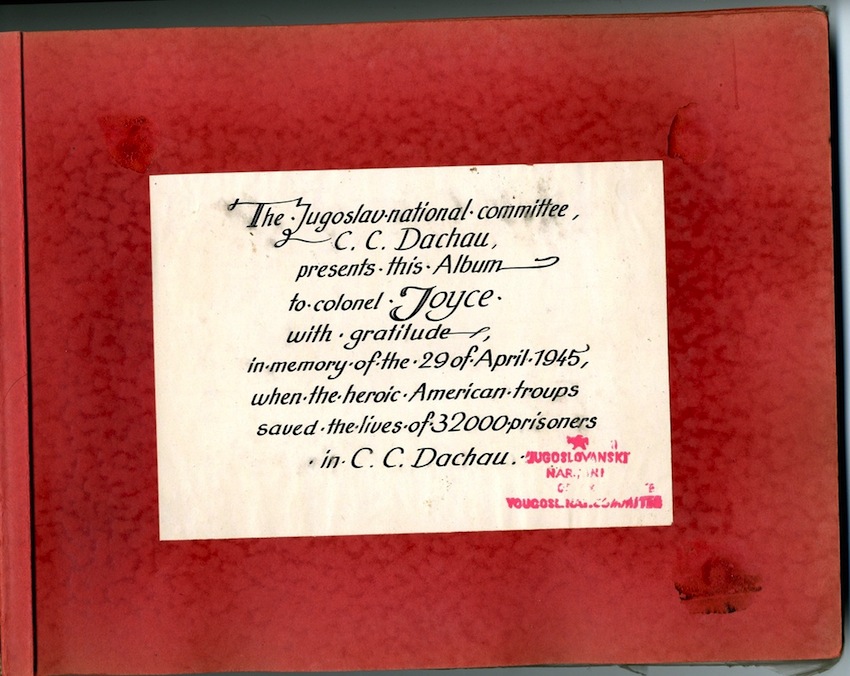

Joyce brought home a photo album given to him by a group of appreciative Yugoslav prisoners. The book, filled with decrepit papers and aging photos is probably the most striking item to come out of the suitcase at Wayland High. In photographs neatly mounted on sturdy red paper, the prisoners included horrifying images of nearly starved men and piles of dead bodies.

After a few weeks, the Americans set up a higher quality hospital, imported food and medical care, and the death rate soon plummeted. This forced Joyce to turn to a secondary problem: informing prisoners that though help had arrived, they were not simply free to go home.

In a memoir, Marcus Smith, one of Joyce’s medical officers, paraphrased Joyce’s reasoning for keeping the prisoners in place.

There are many good reasons why it is impossible to comply with this request, says Colonel Joyce. There is nowhere to go. The transportation problems are insurmountable. A mass movement of the sort suggested requires an immense amount of planning and coordination … their homes have been bombed out of existence. Furthermore, there is still an epidemic raging, and war criminals are still being sought.

“These men … were naturally crazy to get home,” Joyce told the Globe. “Some would try to climb the wall and get over the dry ditch and the mast at any opportunity. Naturally, the most the sentries did was fire in the air and go after them. We couldn’t and wouldn’t handle them roughly, both because they were mostly our Allies and because they were in no condition to stand any rough handling.”

To provide prisoners some sense of purpose while they waited, Joyce restructured the camp along national lines, and had each nationality set up a committee to help with the camp’s administration. Committees kept track of which prisoners were able to work at tasks like distributing food and cleaning quarters. They were even given the weighty charge of judging evidence of war crimes in their ranks and judging those accused of breaching camp rules.

Joyce recalled the case of an inmate charged with stealing another prisoner’s shoes. He was tried by a third prisoner, who had been a high-ranking judge in his own country. The camp court sentenced the thief with two days of confinement. The judge’s ruling went to Joyce for review.

“That was during the first few weeks,” he said, “and I expected just a memorandum of a few words. But they gave me a document which might have been filed in our own Supreme Court.”

By July, Joyce and the Americans were able to assemble the logistics and medical care necessary to evacuate the camp. When Joyce departed, there were 2,000 hospital patients remaining. Tens of thousands of others had been sent home or to other refugee camps. Joyce’s scrapbook is filled with letters of thanks from the prisoners for his effective administration, and the grim photo album was itself a token of gratitude, a gift from the Yugoslav prisoners’ committee he’d set up.

An album given to Joyce by Dachau prisoners contained striking images of the atrocities he witnessed. (Courtesy of LtColJoycePapers.org)

Stateside

And so Joyce returned from war, this time not as one of many faces on a huge ship, but as the subject of some interest to Bostonians struggling to understand the scope of the Nazi war crimes. In October 1945, he gave a speech to the Boston City Club. That same month, he sat for an interview with the Globe on the couch in his family room at 21 Bertson Street. (In all his years living in military camps and police barracks, he hadn’t yet moved out of the West Roxbury house where he grew up.) He was 46 years old, a “tall, powerfully built, gray-haired man,” in the words of the reporter.

After the war, Joyce found some measure of domestic stability. He married a teacher named Mary Louise. And he didn’t return to the State Police. Instead, they moved to Dedham, then to Plymouth, and finally to Yarmouth on Cape Cod. He worked as an electrical contractor until his retirement in 1956.

But even then, Joyce’s affair with history wasn’t quite over. To celebrate his retirement, he and Mary Louise traveled to Europe. They made their return trip on the Andrea Doria, an Italian luxury liner. It was a cutting-edge passenger vessel for its time, with 11 decks, three above-deck swimming pools, and $1 million of art. It came equipped with eleven watertight compartments designed to keep the boat afloat even in the event of a collision. “You might say it was unsinkable,” Joyce’s students write.

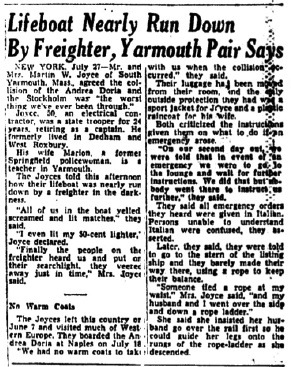

On July 25, 1956, in a dense fog off the coast of Nantucket, a small liner bound for Sweden rammed into the Andrea Doria, bursting open a gaping hole in its side. The damage caused the ship to tilt dramatically to the right. Eleven hours after the collision, the Andrea Doria was fully submerged.

Courtesy of LtColJoycePapers.org

Martin and Mary Louise Joyce escaped on a lifeboat, only to be nearly overrun by a freighter in the search party. Joyce, once again, found himself quoted extensively in the Globe. “All of us screamed and lit matches … I even lit my fifty cent lighter,” he told the paper. The freighter did eventually spot them in time to swerve out of the way.

Among passengers and crew members, 46 people died. There were 1,660 survivors. It was an extraordinary sea rescue, one that captivated America, where people watched the ship go down on the new medium of television.

“The collision of the Andrea Doria and the Stockholm was the worst thing we’ve ever been through,” Joyce told the paper, a telling statement from a man who witnessed Dachau. Yet, of everything that Joyce lived through, surviving the Andrea Doria wreck is the first one mentioned in his obituary. Joyce retired to Yarmouth, and in 1962, he passed away at Cape Cod Hospital at the age of 63, of causes that remained unknown to Wayland’s students. He was survived by his wife and six siblings, but no children.

Remembering Joyce

As the Wayland students produced their research, they built ltcoljoycepapers.org, a website to introduce Joyce to the public. Not long after the site launched, Judith Cohen, director of photographic reference collection at the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., stumbled across it and reached out to Delaney.

Two years after Delaney pored over the suitcase in the old Wayland history department, Cohen arrived at the new Wayland High School. At an evening presentation this past June attended by the students and a smattering of parents, veterans, and interested Wayland residents, the class handed the materials over to Cohen, who sounded grateful for the archival work they’d already put in (and a bit nervous to see the public paging through the fragile material).

Perhaps the biggest outstanding question in all of this was just how the briefcase of Joyce’s possessions made its way to Wayland High. Joyce, of course, had no living descendants or close relatives who could help advise. Delaney asked his retired colleagues from the history department, many of whom remembered seeing the documents or using them in the classroom. No one could say for sure just who’d brought them there. Most agreed that the best bet was Bob Scotland, a former Wayland history teacher who had served in the 7th Army as a medic and told grisly war stories, including some about prisoner of war camps. Scotland died, also childless, in 1999.

“There’s really no one for us to give a call,” Delaney says. Still, his best guess is that Joyce and Scotland did know one another, and Joyce handed over the documents thinking they might make for a useful educational supplement. (That was, evidently, a good bet.)

For Delaney, the June ceremony concluded a two-year project into which he’d invested more than just time. Joyce had become something like a long-lost grandfather, he admitted to the audience that night, a man whose war stories he’d grown to know by heart.

The students, too, became his ardent defenders. Their biography is written, at points, almost like an argument for Joyce’s sainthood. (“While liberating the Dachau Camp in Nazi Germany … Joyce would demonstrate unforeseen leadership with grace and humanity to all who crossed his path,” reads one passage.)

Courtesy of LtColJoycePapers.org

Kevin Skronkowski, one of those students, visited Washington, D.C., during spring break to tour colleges when he realized his family was driving right by Arlington National Cemetery. He asked his parents to take a detour and see if they could find Joyce’s grave.

“It was me, my sisters, and my parents just going around grave by grave. And my little sister found it first, so we ran over,” recalls Skronkowski, now at Dickinson College in Carlisle, Penn. The rest of the family came over to see the plain white gravestone. Skronkowski and his family took a few pictures to bring back to Delaney’s class. They noted the simple inscription with the dates he served and the rank he attained.

“It was weird because it was this guy who we had learned so much about in class. And he was right there,” Skronkowski says.

You have to imagine that Joyce, a childless veteran who spent a life defending his own generation but might have been forgotten by the next, would have been only too happy to have the visitors from Boston.