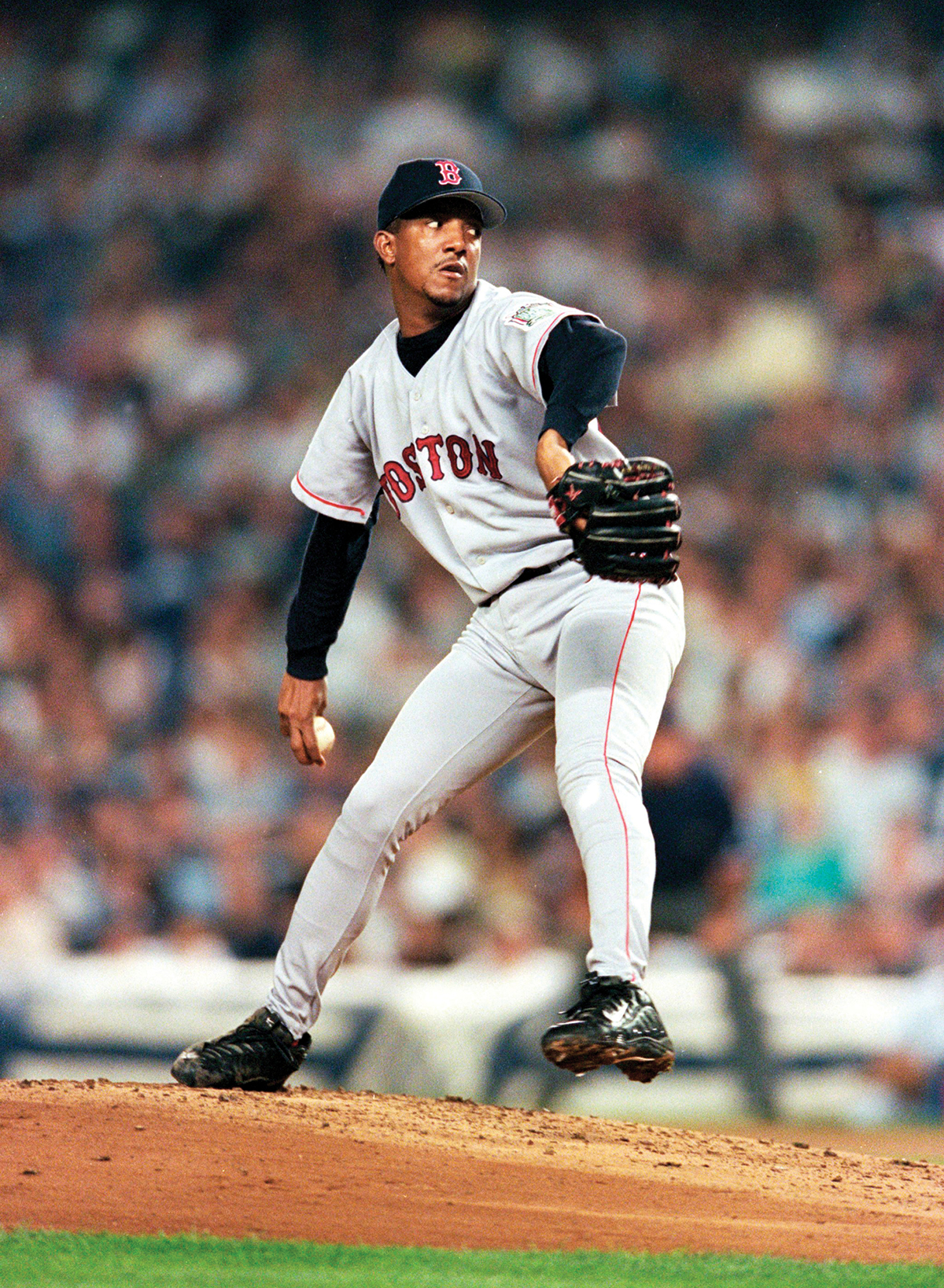

Pedro Martinez’s Greatest Game

Photograph by Ezra O. Shaw/Allsport via Getty Images

With both feet on the rubber and his shoulders squared to home plate, Pedro Martinez stood on the pitcher’s mound in the Bronx like he owned the damn thing. He fanned his black leather glove in front of his face, then gently nested the ball and his right hand within it and peered over the top of his hands like a praying mantis.

Fastball, away, for a called strike to leadoff batter Chuck Knoblauch; things were looking good. It was Friday, September 10, 1999, Martinez’s 26th start of the season and a month before the Sox would face the Evil Empire in the American League Championship Series.

It had been 81 years since the Sox had won a World Series; the rivalry was decidedly one-sided.

Then, with his second pitch of the night, Martinez hurled a biting fastball that sailed up and in, grazing the underside of Knoblauch’s left arm. The Yanks didn’t rush the field like they would a few years later, during the infamous 2003 playoff game in which Martinez ignited a bench-clearing brawl by whipping a fastball behind the head of outfielder Karim Garcia, but it was a clear message: The plate belongs to me. Tonight and every night. All of it.

In just his second season with the Sox, Martinez was starting to develop a taste for hitting Yankees batters. By the time he finished his seven-year run in Boston, in 2004—during which time he faced Boston’s hated rival 33 times, including six playoff games—Martinez had plunked New York hitters a staggering 20 times. “Pedro wasn’t anybody’s favorite, obviously,” former Yankees manager Joe Torre recently told me.

After Knoblauch took his base, Martinez threw a first-pitch fastball to Yankees shortstop Derek Jeter, then another, both balls. When Knoblauch sprinted to second base, attempting to steal, Boston catcher Jason Varitek fired to Jose Offerman on the bag for the first out. Martinez then threw five more fastballs—for a total of nine straight to open the game. The last was a 97-mile-per-hour heater that even Jeter, in the prime of his career, hopelessly swung through for strike three. It was Martinez’s first K of the night.

With two outs and the bases now empty, Yankees outfielder Paul O’Neill approached home plate and began a deliberate, time-sucking routine just outside the batter’s box, adjusting his helmet and gloves, digging in. No problem. Martinez had grown accustomed to this tactic, adapted to it, understood it. The Yankees are trying to take me out of my rhythm, he thought. Martinez liked to work fast, push the pace, force the issue. The Yankees were hell-bent on slowing him down.

As O’Neill continued to primp, Martinez tried to settle himself, squatting on the back of the mound like a catcher facing home plate. He exhaled deeply. When O’Neill was finally ready, Martinez delivered a changeup that O’Neill grounded right at first baseman Mike Stanley, who stepped on the bag for the inning’s final out.

In the top of the first, Martinez threw only 11 pitches: nine fastballs, two changeups. Five balls and six strikes. From his experience as a player, broadcaster, and manager, Torre knew that the great pitchers tended to assert themselves as the game progressed, that Martinez would likely get better with each inning, and that New York’s best chances would come early, if at all. “He could be overwhelming,” says Torre, now the chief baseball officer for Major League Baseball. “Our plan against Pedro, it was sort of like when I was a player [in the National League] when we went to play Los Angeles and we got either [Sandy] Koufax or [Don] Drysdale. With the rivalry and everything else, we knew we were going to face him.”

Martinez notched his second strikeout of the night against Bernie Williams to start the bottom of the second inning, followed by a routine fly ball by first baseman Tino Martinez. Then, with two outs and the bases empty on a 1–1 pitch, aging Yankees designated hitter Chili Davis belted a careless 90-mile-per-hour fastball into the right-field seats for a home run, giving the Yankees a 1–0 lead and a major confidence boost. Davis, who currently serves as the Red Sox hitting coach, told ESPN.com this spring that Martinez came inside with three consecutive pitches, the last of which he whacked over the fence for the lead.

But the videotape doesn’t lie. In reality, Martinez started Davis off with a curveball on the outer half of the plate for called strike one. Martinez followed with a 95-mile-per-hour fastball on the inner edge for a ball—he barely missed—then went back to the opposite side of the plate. Varitek was set up with one foot nearly in the opposite batter’s box expecting the pitch to be away, but Martinez yanked the offering and left the ball over the heart of the strike zone.

Pow.

The fans roared like wild animals. At moments like this, the pitcher’s mound at Yankee Stadium was smack dab in the middle of the lion’s den, music blaring from the loudspeakers, the bloodthirsty crowd howling from the uppermost reaches of the balconies. In the late ’90s, in the Bronx, a Yankee circling the bases seemed like a predatory ritual. “I missed location,” Martinez rightly told me 16 years later.

Martinez was approaching his 28th birthday and had already faced the Yankees five times in his career, winning three games and losing two. His performances had been good, not great. For Martinez, though, all of those games effectively served as informational interviews, opportunities to see his enemy firsthand, to witness how they approached him, and to see how they reacted. “If you take the same approach against them all the time, they’ll figure it out right away,” Martinez says. “That whole team was like that. They’d take you deep into the count. You had to really observe that whole lineup.”

So Pedro watched. And with the Sox down 1–0 in the second inning, no one envisioned that Martinez was about to turn in his finest masterpiece and what Globe sports columnist Dan Shaughnessy recently called “the greatest game ever pitched in Yankee Stadium.”

At the turn of the millennium, the Yankees were at the peak of their dominance, heading for the second of three consecutive World Series titles—they’d win four in the span of five years—with a roster that qualified as a true embarrassment of riches. Alongside the 1927 Murderers’ Row team led by Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Bob Meusel, the 1998 team—which set a record for team wins—had arguably been one of the very greatest Yankees teams of all time. The starting lineup changed little the following year. Among New York’s hitters, O’Neill and Williams would each finish their career with a batting championship; Knoblauch, the second baseman, had hit .341 in 1996 with the Minnesota Twins; and in 1999 Jeter was in the midst of compiling a career-best .349 average. The lineup Martinez faced that day was professional and patient, a surgical complement of skilled batsmen who could hit most anything, anywhere, against anyone. “We thought the ’98 team, 1 through 25 [on the 25-man roster], was one of the best in history,” recalls New York pitcher David Cone. “The entire roster was so deep. We had [former All-Stars Darryl] Strawberry and [Tim] Raines coming off the bench.”

By the time Boston rolled into New York for a three-game weekend series in September 1999, New York held a spongy six-and-a-half-game lead over the Red Sox with 23 games left to play in the regular season. The Yankees were gearing up for another playoff run and the Sox, clinging to a three-game lead over the Oakland A’s for the wild-card spot, were hoping to make the playoffs for a second consecutive season—something the team had not accomplished since World War I.

Martinez, meanwhile, was in the midst of a historic run that would have awed Secretariat. He would finish the season with a record of 23 wins and just four losses, with a 2.07 earned-run average and career-best 313 strikeouts; his 13.2 strikeouts per nine innings rank second all-time to Randy Johnson’s 13.4 in 2001. But Martinez had saved his best for last: Over his final seven starts of the season, he went a sterling 6–0 with a 0.82 ERA and a preposterous 96 strikeouts in 55 innings, which translated into a remarkable 15.7 strikeouts per nine innings pitched.

As it happened, Martinez was pitching with the benefit of an extra day’s rest, taking the mound in New York five days after his last start instead of the customary four. It was a strategy that both protected Martinez’s slight frame and maximized his ability. When given that extra day of rest in 1999, Martinez was an ungodly 12–0 with a 1.27 ERA and 133 strikeouts in 92 innings, perhaps the closest thing to a sure thing the game has ever seen. And he did all of this, of course, in the midst of baseball’s steroid era—when chemically enhanced hitters generated eye-popping offensive numbers and forever tainted the game.

“It was ridiculous that year,’’ recalls Sox first baseman Stanley, a former Yankee who played with pitching legends Nolan Ryan and Roger Clemens. “Pedro was just—he was unbelievable. He was the guy— and you’d get this feeling with Nolan and Roger—you’d just feel like, ‘Give him a run and we’re good.’ That year, not to slight anybody else, but you’d come to the park and Pedro was pitching, and you knew all you’d need was a couple of runs. It was like, ‘Who’s pitching? Pedro. Let’s score a couple of runs and that’s all we need.’”