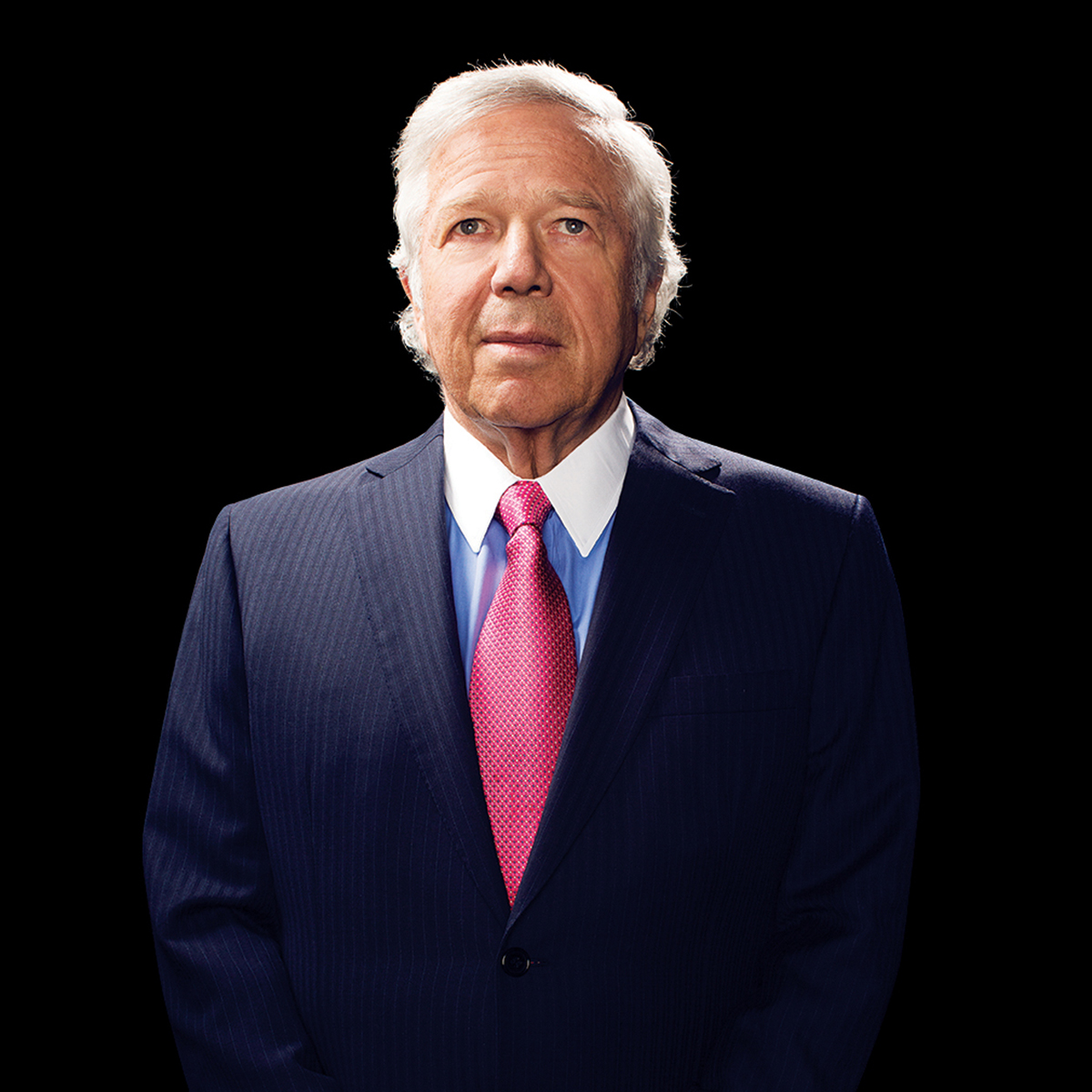

‘I’m Robert Kraft. Do You Know Who I Am?’

Photograph by Scott M. Lacey

The past couple of years, he’s been making calls that begin like so: “This is Robert Kraft. Do you know who I am?”

Andrew Schiff answered the phone to that question last year at the Rhode Island Community Food Bank. He said to Robert Kraft, “I know who you are. But I have no idea why you would be calling me.”

“I have good news for you,” Kraft said. He told Schiff that he was giving his nonprofit, which teaches culinary skills to unemployed adults, $100,000.

Kraft also told Schiff not to tell anyone about the call. And there was more: In order for Schiff to get the money, he’d have to raise another $100,000 from others.

Two hundred thousand dollars—that would cover a year of the culinary program’s operating costs, Schiff thought. But he’d have an easier time convincing others to give if he could use Kraft’s name. Could he, please?

There was a pause.

“Okay,” Kraft said.

The generosity was no surprise. With his wife, Myra, as the point person, Kraft had long been one of Boston’s biggest philanthropists, to the tune of more than $100 million over the past three decades. We know that, just as we know that he’s made a fortune in the box-making business and that his Patriots have won four Super Bowls and that his beloved quarterback, Tom Brady, was in trouble this year over underinflated footballs as Kraft fumed at the NFL over the whole overblown Deflategate affair.

But something’s changed since Myra died four years ago. Robert is now 74. In a sense, he’s had to start over without her. He’s still writing checks, still feeding the homeless, still going off to charity board meetings. He’s still busy by nature. Still, in fact, driven. Why, just this summer he took 19 Hall of Fame football players on a weeklong trip to Israel, on his own dime.

Still, something about Robert Kraft feels…off. Even—or especially—when he’s being generous. For example: At the end of their Israel trip, the Hall of Famers were asked to describe—in front of a Kraft Sports Productions film crew—how the journey had changed them. Their impromptu salutes to the Holy Land and, incidentally, to Kraft were broadcast via the Web so all the world could see that the greatest athletes had made a spiritual pilgrimage alongside their guide and benefactor.

Something seems off, too, in those out-of-the-blue calls from a powerful billionaire to struggling nonprofits. Claudia Green, the executive director of English for New Bostonians, was meeting with staff early this year when her phone rang. The caller ID said “the Kraft Group.” She didn’t know who that might be, but sensed it could be important, so she shooed everyone from her office as she picked up the phone to: “This is Robert Kraft.” She knew who he was.

By this point, he was onboard with nonprofits passing the word: “I encourage you to use the Kraft name with other donors,” he told Green. She says the impact of her conversation with Kraft was “a lifetime in two minutes.” Offers like these don’t come along every day.

And something’s been off, as well, in the way Kraft has swung between rage and desperation in trying to control the damage of Deflategate, the latest scandal that threatens to tarnish his team’s image. At the podium, staring into the cameras and declaring the team’s innocence, Kraft hasn’t been buffing and shining his image the past year so much as demanding: Do you know who I am?

Though not a question, it begs an answer, and I have conflicting evidence. Kraft really has become a hands-on giver—going to the Rhode Island Community Food Bank himself to check it out, and finding jobs for some graduates in Gillette Stadium’s cafeteria. He’s committed to doing good. But the phone calls, the grandstanding, the unfettered rage at the NFL are curious, as if now Robert Kraft, who has gotten everything he has ever reached for, is worried, after years of polishing his image into a blinding gleam, that we still don’t know who he is.

A call to a longtime Bostonian, someone who has studied Kraft, someone who’s given the man a lot of thought for many years, unlocks the door to an answer:

“Robert Kraft,” he says, “is the neediest man I have ever met.”

Need cuts many ways. once upon a time, long ago, Kraft needed money.

He was Bobby then, a boy in Brookline in the ’40s, his elementary school a block from where Jack Kennedy was born a generation earlier. Bobby’s father, Harry, owned a small dress business that never did well; the family lived in a humble apartment.

Bobby’s childhood was ordered by his father’s strict religious beliefs: school, Hebrew class from 4:15 to 6:15 Monday through Thursday, then home for dinner. Saturday after services, the Kraft children—Avram, Bobby, and Elizabeth—would go home with their father, where he would further explain the Bible passages brought up during the service. Bobby would not carry money or ride streetcars on the Sabbath; the family had no car. His friends knew they had to wait for the end of the Sabbath, when the sun went down, for Bobby to come out and play, which meant that in the summer they had to wait a long time. If they went to the movies, a friend would pay.

Avram and Bobby always worked—Bobby hawked newspapers at Braves Field until his favorite team abandoned Boston for Milwaukee when he was 12.

Though money was tight, Harry dreamed that Avram would become a doctor, and Bobby a rabbi. He himself had become something of a spiritual leader in Brookline, serving as a moral guidepost for scores of families. Robert still gets an occasional letter telling him what his father, dead now for 40 years, meant to the devotional awakening of the writer half a century ago.

Bobby, however, had different ambitions. As a teenager, he would ride his bike past the house of the dean of the Harvard Business School in Cambridge, hoping to drum up odd jobs. Bobby—then Bob—became president of his high school class. He would get a scholarship to Columbia and play intramural sports, something he was never allowed to do at home because the games were held on the Sabbath.

Kraft was 20 years old when he first saw Myra Hiatt in a Boston coffee shop; she was on a date, but when she got up to leave, he winked at her and she winked back. Somehow, he found out her name and came up with her phone number at Brandeis, where he called the very next morning. Her roommate told Kraft that Myra was at the library, so Kraft went there and searched for an hour before finding her. They went on a date the next night, and at the end of it she proposed marriage to him.

Kraft and his late wife, Myra, posed in front of a Patriots logo painted on their Brookline lawn in 2005. / Photograph by Michel Dwyer/AP Images

They married when he graduated from Columbia, and she got pregnant on their honeymoon. Within five years they had three boys.

Kraft did get into Harvard Business School, and after graduating had offers on Wall Street. But Harry convinced him to come home and work for his father-in-law, Jacob Hiatt, a box manufacturer who had lost much of his family in the Holocaust.

Kraft hated working for Jacob, who was controlling and penny-pinching. But Kraft quickly made enough money in the stock market to get into the packaging business himself. His big break came in 1971, when he won a contract with a Canadian brown-paper mill. That was the start of International Forest Products.

Kraft was on his way to getting rich, buying Jacob’s company and, eventually, the Patriots.

The Patriots became an obsession. Kraft had been a fan since the team’s inception in 1960. Their first year in Foxboro, in 1971, Robert bought season tickets, which triggered a fight with Myra because she thought football was barbaric and besides, they couldn’t afford season tickets. But he was determined to share with his sons a slice of life he’d missed as a boy; on Sunday mornings, he’d leave them notes under their pillows dismissing them early from Hebrew school so they could attend Patriots games. It was a long time before Myra found that out.

Twenty-three years later, Kraft bought the team, one of the worst-run in the NFL, saving it from moving to St. Louis. He’d had his heart broken back in 1953, when the Boston Braves left town, and he wouldn’t let that happen again, even if it cost $172 million, then a record for any American sports franchise. Which at the time triggered another fight with Myra. “The summer house better be in my name,” she warned Robert, not entirely kidding.

Now, as owner, he would remind himself of just what he’d done for Boston fans by wandering outside Gillette Stadium on every football Sunday, chatting up the faithful. He was one of them, he’d tell them—he used to hold season tickets up in section 217.

Overlooking the crowds, Kraft’s box at Gillette would take on the rarified air that comes with supreme success—Jon Bon Jovi and Mark Wahlberg and fashion mogul Tommy Hilfiger and other stars regularly appeared at games alongside the owner. Myra, meanwhile, became the team mother, cooking chicken soup for some players during the Jewish holidays. Which would become part of the Patriot Way.