Brian Peixoto’s Final Appeal

Brian Peixoto photographed on November 18, 2015, inside MCI-Concord. / Photograph by Dana Smith

Just after dusk on a foggy January night, a black pickup truck screeched into the parking lot outside a Westport fire station. The driver, wearing a white sweatshirt smeared with blood, held a small boy wrapped in a blanket. The child was pale and without a pulse, his brown eyes lolling upward.

Firefighter Brian Legendre, who had grown up near the small fishing town in southeast Massachusetts, recognized the driver from high school and listened to his former classmate, Brian Peixoto, describe finding the three-year-old vomiting and banging his head against the floor of his home, roughly a mile away. Peixoto said he had tried to revive the toddler—named Christopher—by slapping him, shaking him, and throwing cold water on his face. After clearing a handful of throw-up from the boy’s mouth and trying CPR, he rushed to the fire station for help. With him were his girlfriend and the child’s mother, Ami Sneed, along with the boy’s four-year-old sister, Tarisa, who was watching TV with Christopher when he started getting sick. “[Christopher] was throwing up at Brian’s house,” Tarisa would later say, “and he did not want to wake up.”

At first, Legendre and the two other firemen on duty that night wondered if the boy was epileptic as they loaded him into the back of an ambulance and raced toward Saint Anne’s Hospital in Fall River. But that hunch ended the moment they cut away the boy’s blue jeans and T-shirt and saw bruises on Christopher’s chest, arms, head, and forehead, as well as scratches on his head. Treating the fragile patient like a trauma victim, the firemen stabilized Christopher’s spine and briefly pulled the ambulance over in order to snake a breathing tube past the boy’s cracked lips and down his windpipe. Then they called ahead to report the possibility of a suspicious death.

Michael Roussel was the first detective to arrive at the hospital. There are few strangers in Westport or in neighboring Fall River, and Roussel recognized 26-year-old Peixoto from a dive bar called Oasis, where he worked security and Peixoto checked IDs as a bouncer. Peixoto wasn’t Christopher’s father, but for the past couple of months, 20-year-old Sneed and her kids had been spending most nights at his home. While doctors in the emergency room tried every Hail Mary in the medical playbook to revive the unresponsive boy—including jabbing a needle full of adrenaline into the marrow of his leg—Roussel talked with firefighters and medical personnel about Christopher’s bruises.

By then, Peixoto had already taken off. A hospital security guard asked him to go home before Christopher’s father showed up, leaving Sneed to field questions from the cops. Roussel and another detective spoke to Sneed, who was skinny, about 5 feet tall, and had auburn hair that complemented her hazel eyes. The detective wanted to know about the bruises. She told him that she’d noticed a small one on her son’s ear, which she thought came from a bite by his sister, another on his leg, and a third, faded bruise on his forehead, but denied ever seeing significant bruising on Christopher’s head. Not satisfied, the detectives asked flat out why the boy was marked. She had no answer, but added that Peixoto did not have a temper and “would not do this in my presence.”

At 7:02 that night, January 22, 1996—less than an hour after Peixoto had rushed Christopher to the firehouse—doctors declared the boy dead. The emergency chief and his staff persisted with lifesaving efforts longer than normal for only one reason: the patient was three years old. By now, the hospital was lousy with law enforcement from multiple agencies, including Westport Police, Massachusetts State Police, and the Bristol County District Attorney’s Office. Cops, nurses, and doctors filed into the hospital room and hovered over the body of the boy, who died in diapers and a hospital gown, a breathing tube still stuck down his throat.

Police began trying to piece together what happened. Within hours of Christopher dying, they interviewed Peixoto and Sneed at the police station. Peixoto was in one room. Sneed sat in another. A portrait of the couple emerged.

Peixoto had first met Sneed at a pig roast about six months earlier. Florida-born, she was a free spirit who grew up in the area. Peixoto, like many from Fall River, came from a family of cotton-mill workers. He was on the rebound from a relationship that had left him with a daughter named Amber, who was four years old when Christopher died. Neither possessed a criminal record. In addition to taking nursing classes, Sneed worked one day a week making sandwiches at Subway. Peixoto had worked for a company as an unskilled laborer forging precast molds of prison cells. He’d fallen down on the job and injured his neck but hadn’t begun collecting workers’ compensation. To make ends meet, he worked nights at Oasis.

When Sneed couldn’t pay her electric bill that winter, she and her two kids started spending the night at Peixoto’s place, the basement of a house he shared with a friend who had two children of his own. Though his own perch wasn’t that lofty, Peixoto looked down on Sneed’s lifestyle: She was on welfare and as a teenager had two kids out of wedlock. She didn’t even have a driver’s license.

In the interrogation room, Peixoto wasn’t doing himself any favors. He told detectives about a Ricki Lake episode on unwed mothers they’d been watching earlier that day and a derogatory remark he’d made during the show that upset Sneed and sent her into a tantrum, packing her clothes into a garbage bag before Peixoto apologized and she decided to stay. It wasn’t long until they both heard Tarisa cry for help. Sneed, who heard a loud bang coming from downstairs and thought the television had fallen off its stand, followed Peixoto down to the basement. Though she couldn’t initially see Christopher because Peixoto was hunched over him, she heard Peixoto say that Christopher was throwing up and banging his head on the floor. When Peixoto lifted Christopher, Sneed told police, her son spit up, rolled his eyes back into his head, uttered the word “Mommy,” and gasped for air. Peixoto thought about calling an ambulance, but knew it would be quicker to drive. They arrived at the firehouse minutes later.

As Sneed’s interview neared an end, police noticed her starting to cast suspicion on Peixoto for the first time. Peixoto had told police that Christopher sometimes wet his pants, blurting out, “I would be pissed off at Christopher for wetting himself but I didn’t want him dead.” Sneed would later tell the cops that Peixoto got angry when Christopher wet himself, and said he scolded her for not disciplining her son enough. When detectives asked who had the opportunity to harm Christopher, Sneed answered, “He’s the one who had to have done it. I haven’t touched him.”

Police arrived at Peixoto’s home just before 2 o’clock that morning, taking photos and bagging up a pillow and a towel from what was fast becoming a murder scene. Investigators learned that Christopher had fallen down some steps and broken his collar bone roughly a week and a half before his death, but that detail seemed minor compared with other information that was streaming in. Besides the slew of bruises on Christopher’s head, doctors found less obvious damage on the boy’s body, such as bloodied lips and the bite mark. Saint Anne’s emergency doctor John Arcuri, who mentioned that Christopher’s diaper had been soiled, told police he believed the injuries were sustained from abuse. Sneed’s mother, Janet, said she suspected Peixoto of beating her grandson and that Christopher once told her Peixoto had smacked him. By the morning after Christopher’s death, evidence of a crime was already coming together.

The man responsible for determining the cause of death was James Weiner. Real-life medical examiners’ work conditions are starkly different from the pristine morgue labs shown on television. Weiner’s office in Pocasset, occupying the basement of an abandoned Cape Cod mental hospital slated for demolition, was cursed with a lack of drainage and a corroding septic tank. Rather than simply let each body’s “effluent”—that is, liquid waste—seep down a drain in the floor, medical examiners there had to collect the liquid in 5-gallon buckets and pump it back into the cadaver at the end of every postmortem.

During Christopher’s autopsy, at which his body was examined both on the Cape and in Boston to accommodate a forensic dentist, eight cops gathered around Weiner’s exam table waiting for answers. Over the course of two days, Weiner discovered injuries that had gone unnoticed at the hospital: Christopher’s penis and scrotum were badly bruised and there were “at least eight separate impacts” to his head. The doctor also noted that Christopher’s skull was fractured and found extensive bleeding beneath the boy’s scalp. The doctor was certain, he told police, that the fracture was the cause of death, explaining that “either a blunt object struck the head or the head struck a blunt object.” There was no way, Weiner concluded, for Christopher to inflict that much damage on himself short of “falling out of a tree limb and landing on his head from a 10-foot height.” He ruled it a homicide, declaring that a blow to the head had likely killed Christopher within minutes. “The onset of symptoms would be immediate,” Weiner told detectives, “and the victim would be at the very least unconscious and unable to function in a normal manner.”

To police, a motive was beginning to appear. Peixoto and Sneed had gotten into a fight over the Ricki Lake show, and then Peixoto flew into a rage after Christopher wet his pants. As prosecutors later suggested, this led Peixoto to smash the boy’s fragile skull against the basement floor eight times. Christopher’s death was now a murder case.

On January 24, the afternoon that the autopsy was completed, investigators called Sneed in for another interview. This time, important parts of her story suddenly began to change. In her new story, Peixoto went downstairs alone when they heard Tarisa scream for help, and she stayed upstairs for three long minutes before going down to check on Christopher. From the top of the stairs, she told police, she heard about five loud bangs that “sounded like someone punching a wall or something.” Investigators then asked Sneed how, in her opinion, Peixoto had injured her son. It “had to be the wall,” she replied.

The motive was still thin, but detectives had what they needed. At 8:15 p.m. that night—49 hours after Christopher had been declared dead—state and local police arrested Peixoto on a charge of first-degree murder.

The story about a suspected baby killer along the South Coast spread like wildfire. “Westport tot was killed over wet pants,” the Boston Herald blared on its front page. “Mom: I heard banging,” read another newspaper’s headline. The tabloid television show Hard Copy sent a film crew to cover the crime. The media zeroed in on the Ricki Lake show about unwed mothers, and how a small-town bouncer beat his girlfriend’s son to death after watching the segment that mirrored her lifestyle. Renee Dupuis, a Bristol County assistant district attorney who had successfully prosecuted priest James Porter—one of the first clergymen in Massachusetts sentenced to prison for sexual abuse—was in charge of the case against Peixoto. “When the child messed his pants,” she said during Peixoto’s arraignment, “he just lost it.”

Having no experience with lawyers or the criminal justice system, Peixoto decided to take what the state gave him: a public defender who spent most of his time representing drug dealers. He wore a loud green suit jacket, Peixoto recalled, and laced his sentences with profanity. During pretrial motions, the defense attorney mistakenly included details of unrelated cases he’d worked on. Not one to mince words, Peixoto called him a “fast-talking, slick, used-car-salesman type of lawyer.” After nearly a year of fruitless efforts to meet in person and prepare a defense, Peixoto finally sat down with his attorney four days before trial. Dupuis was willing to drop the charge down to second-degree murder, the lawyer excitedly reported, meaning Peixoto could likely walk away with a sentence short enough to see his young daughter graduate from high school. Peixoto started crying. “I’m not pleading guilty to something I didn’t do,” he said. When his attorney responded, “I guess I can whip up a defense for you by Monday,” Peixoto recalled, he fired the man on the spot. The attorney did not respond to requests for comment.

Peixoto’s family searched for a new lawyer, ultimately retaining Raymond Veary, an amateur actor who moonlighted at the local playhouse, where his roles included George from Of Mice and Men. A prosecutor for more than two decades, Veary had recently converted to criminal defense. With 60 days to prepare for trial, Veary thought Peixoto’s prospects looked bleak. “As the evidence currently stands,” he wrote Peixoto’s family in a letter seeking $25,000 before the trial began, “the child died as a result of multiple trauma, most likely the result of a single beating. Based upon this evidence, the most likely explanation lies with Brian, regrettably.”

Dupuis, in the meantime, had secured a new medical expert to testify alongside Weiner. It was a familiar name among criminal attorneys: “Just received this from the prosecutor,” Veary stated in a fax a week before the trial. “They’re bringing in Dr. Newberger.”

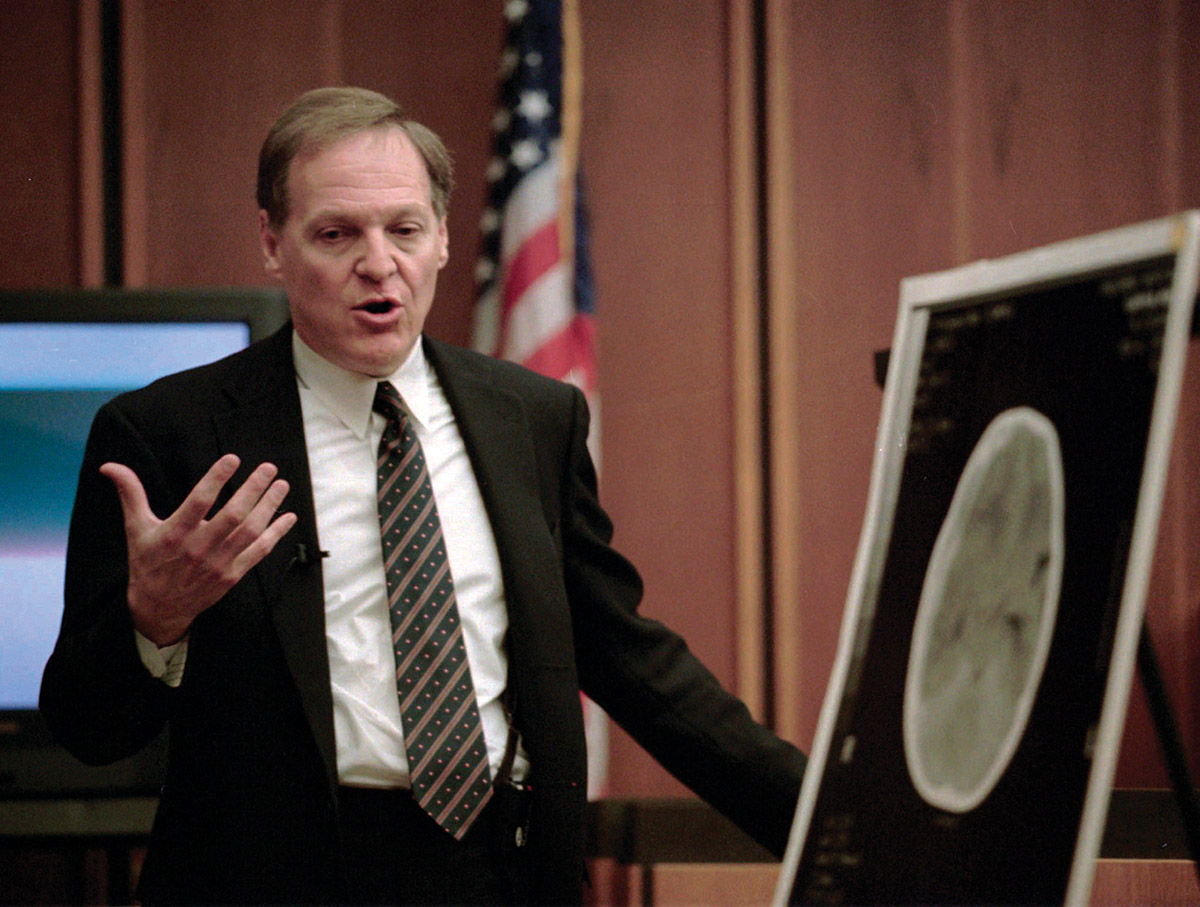

Eli Newberger testified during Peixoto’s trial as well as the notorious Louise Woodward “shaken baby” trial. / Photograph by Boston Globe/Getty Images

The trial began in March 1997. Eli Newberger, a child-abuse expert, was the state’s third witness called during the weeklong trial. Educated at Yale, he was a senior staffer at Boston Children’s Hospital, earning a side income reviewing medical records and testifying as an expert. From the witness stand, Newberger studied exhibit number 47 and told the jury why the “huge area of bruising” on Christopher’s shaved head above his right ear showed that the boy had been struck multiple times. “The kinds of impacts would not be, for example, the kinds of impacts that you see from a child falling down,” he explained. Instead, the impact would require “the application of a force comparable to what you would get if you were to fall from a second-story window onto concrete.”

Based on the color of Christopher’s bruises, Newberger testified, all but a few of the contusions were fresh signs of abuse inflicted at the time of death. This aligned with his opinion that Christopher’s attacker was brutal and intended “as much suffering be endured by the victim as possible.” The injuries to Christopher’s penis, Newberger testified, included apparent pinch marks often seen in cases where adults grow frustrated with young children for whom toilet training has become a problem. It was the state’s case encapsulated—that Peixoto, already angered over his Ricki Lake argument with Sneed, flew into a violent rage when he discovered Christopher had wet his pants and beat him to death while Sneed was upstairs. Dupuis called the marks on Christopher’s penis the most important evidence in the case, telling jurors, “[Peixoto] left his mark on that baby like the Z from Zorro.”

Sneed, by then pregnant with her third child by another man, testified tearfully for the prosecution. When asked why her account of what happened had continued to evolve, she said, “I didn’t lie, I just didn’t tell them everything.” Peixoto took the stand and was asked who had harmed Christopher, if not him. He could only answer, “I don’t know.”

Veary’s defense wandered. He mentioned that Christopher’s fall down the stairs and the broken collar bone troubled him, and that he was puzzled about how such a brutal attack could take place without a single cry from the victim. He’d hired an independent medical expert to review the evidence in search of “alternative explanations,” and that expert found flaws in the opinions against Peixoto. But Veary never called the expert to testify, and didn’t fight the medical conclusions made by the prosecution’s experts. Veary also suggested Christopher’s death had been an accident, or that perhaps Tarisa or the roommate’s dogs had somehow been involved, before finally acknowledging the only other possible perpetrator: “I ask that you consider [Sneed].” Veary, now a Massachusetts Superior Court judge, declined to comment for this article.

During her closing remarks, Dupuis boiled her case down to a simple question: Who had the strength to beat this child to death—little Ami Sneed, or a “five-nine 185 bouncer”? With no substantial physical evidence besides the boy’s corpse, Peixoto’s conviction rested on the testimony of the medical experts who were certain that Christopher’s injuries had killed him immediately. “And in the classic whodunit,” Dupuis said, “it’s either got to be his mother or the defendant.”

It took the jury just 93 minutes to return a guilty verdict. Then Judge Charles Hely sentenced Peixoto to prison for the term of his natural life. “I just want to say thank you,” Sneed told the courtroom, “to everyone that put all their time and effort into helping solve this, and charge Brian with the charge that he deserves.”