A Rumble in the Granite State

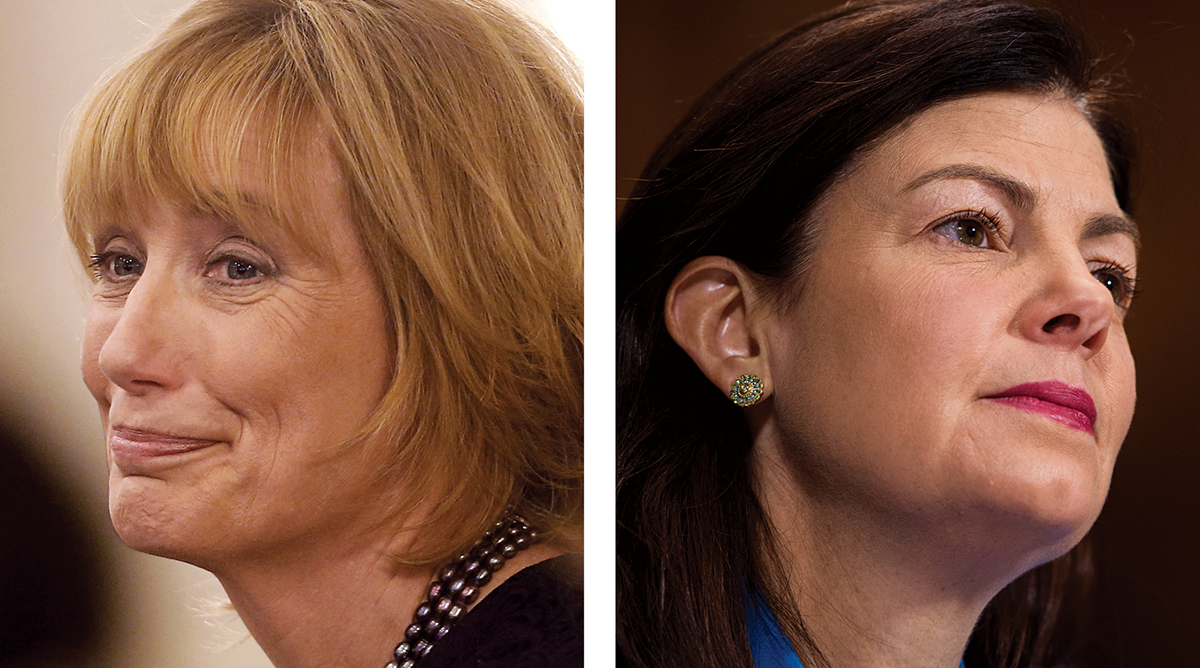

New Hampshire’s Democratic governor, Maggie Hassan (left), and Republican Senator Kelly Ayotte are facing off in one of the country’s most important political races. / Photographs by Jim Cole/AP Images; Bill Clark/AP Images

Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia’s body was barely cold when Republican Senate leader Mitch McConnell, looking like an angry old snapping turtle, stood in front of a bank of television cameras on Capitol Hill and drew a political battle line unprecedented in living memory.

Because Republicans controlled the Senate, McConnell declared roughly an hour after Scalia died, the party could and would categorically reject anyone Democratic President Barack Obama nominated as Scalia’s successor. He swore that the ninth seat on the nation’s highest court—frequently the tiebreaking vote on the most controversial issues of the day—would remain empty for a year awaiting the results of the current presidential circus.

Whether intentional or not, McConnell’s remarkable pronouncement also shone a spotlight on 2016’s undercard fight for control of the U.S. Senate. Sure, the presidential campaign gets top billing. But the party that controls the Senate, everybody was suddenly reminded, can act as either an enabler of or bulwark against the president’s plans: legislation, treaties, and, yes, judicial nominations that will shape our nation’s laws on issues such as abortion, campaign finance, and energy policy for years to come.

That is particularly crucial given that our next president will be, according to polls, one of the two most disliked and distrusted nominees ever put forward by a major political party. If you loathe Hillary Clinton, you desperately want the Senate to stay in Republican hands in case she wins; if you detest Donald Trump, you just as eagerly want Democrats to gain control and stop him.

This brings us to the friendly little state of New Hampshire, where Democratic Governor Maggie Hassan is challenging Republican Senator Kelly Ayotte. There, unlike the lesser-of-two-evils presidential race, voters have the pleasure of choosing between two well-liked, smart, effective public servants in a race that, especially since the Scalia earthquake, has turned into a white-knuckle fight for control of the upper house.

Democrats need to gain five seats to ensure a majority in the Senate. Their most likely gains, experts on all sides agree, are in Illinois, Wisconsin, and Florida. The next two possibilities, the states that will decide whether it’s Trump or Clinton who gets to choose the crucial ninth Supreme Court justice, are Ohio and New Hampshire.

The Senate races in both states are in a dead heat, and political experts predict the Ayotte-Hassan showdown will stay that way. “I don’t expect [the race] to leave the margin of error” in polls, says Jennifer Duffy, senior editor of the Cook Political Report.

Everybody in politics knows that a mere few thousand votes in the Granite State—maybe a few hundred, or even a dozen—could profoundly change the course of American society. So tens of millions of dollars are flowing in—much of it from Massachusetts or raised by Bay State power brokers including Elizabeth Warren—to target the 750,000 or so voters expected to cast ballots in November. Already a marquee matchup expected to break records for outside spending, the race has exploded into a nuclear political showdown as attack ads from special interest groups drown out the candidates’ own messages and records. In a political season dominated by two widely disliked presidential candidates, New Hampshire’s Senate contest is rapidly getting dragged down by national forces beyond anyone’s control—forcing Hassan and Ayotte to define themselves not by who they are and what they stand for, but by the political distance they can keep from the next president of the United States.

Hassan has found plenty of reasons to visit Boston of late. In April she attended at least four private fundraisers and also delivered UMass Boston’s annual Robert C. Wood Lecture of Public and Urban Affairs. Though largely forgotten today, Wood was a major Boston figure. A leading urbanist at MIT, he spent four years helping President Lyndon Johnson launch the Department of Housing and Urban Development, served as superintendent of Boston Public Schools under Mayor Kevin White, and seriously considered running for governor and senator. He was also Maggie Hassan’s father.

Born in Boston and raised in Lincoln, Hassan attended Brown University when her father was running the Boston schools. She graduated from Northeastern University School of Law in the early 1980s while her parents were living in the South End. “Her father set an example of public service, and both of us thought it was very important to do things that are good for the community,” says Margaret Wood, Hassan’s mother, who now lives in Cambridge. “That’s what we expected in life, and she grew up expecting that.”

Despite her high-profile father, Hassan is hardly the elitist some Republicans try to paint her as. Her father grew up in Florida and was never wealthy. Hassan went to public schools in Lincoln and also in Washington, DC, where her father worked with President Johnson while the city was dealing with desegregation. Later in life, she married a teacher who worked his way up to become principal of the tony Phillips Exeter Academy, and had two children, Meg, 23, and Ben, 27, who suffers from cerebral palsy. Ben now appears with his mother in campaign commercials; she cites his disorder as one of the reasons she got into politics.

When it comes to Ayotte, her common-woman touch is a real part of her appeal; she lives humbly in Washington and returns to New Hampshire on most weekends. “I’ve had to drop her off to get a gallon of milk on the way home from DC,” says Simon Thomson, a former Ayotte staffer. “She hasn’t lost touch.”

Born and raised in Nashua, Ayotte went out of state for college and law school but returned to forge a career in public and private law. She married a pilot in the Air National Guard who flew combat missions in Iraq, and eventually worked her way up to state attorney general, an appointed office in New Hampshire, in 2004—the same year Hassan won her first election to the state Senate. Six years later, Ayotte ran for office for the first time and became a U.S. senator. She rapidly earned her stripes on Capitol Hill and became a frequent guest on the Sunday network talk shows—in part because of her abilities, in part because she’s a rare Republican female officeholder, and in part because of New Hampshire’s first-in-the-nation presidential primary.

Because of her prominence within the Republican Party, it’s easy to forget how new Ayotte is to the political game. In the middle of our phone conversation, Ayotte suddenly, and quite self-deprecatingly, cut me off to apologize for not agreeing to an interview for my 2014 feature about her in this magazine. “Bear in mind, I was attorney general, but this is my first elected office,” she said, explaining why her staff had shielded her from me back then. “Your first term in elected office, you learn a lot.”

It’s hardly what you expect to hear from someone who was on everybody’s short list for Republican vice president in 2012.

Hassan sometimes displays a similarly endearing attitude behind her political façade. Talking about Ben, or about her father as she did at UMass, she occasionally drops her rather robotic campaign rhetoric (comparisons to Martha Coakley are unfortunate but not inaccurate) and becomes the warm, relatable person that people who know her say she is.

Nevertheless, neither candidate is an oratorical wonder, to put it mildly. They are not flashy, in dress or demeanor. They are both professional, both lawyerly: hardworking, careful, thorough, and thoughtful. And now, facing each other from atop the state’s political pyramid, they are forced to all but abandon their natural tendencies and distance themselves from their unpopular parties and presidential candidates.