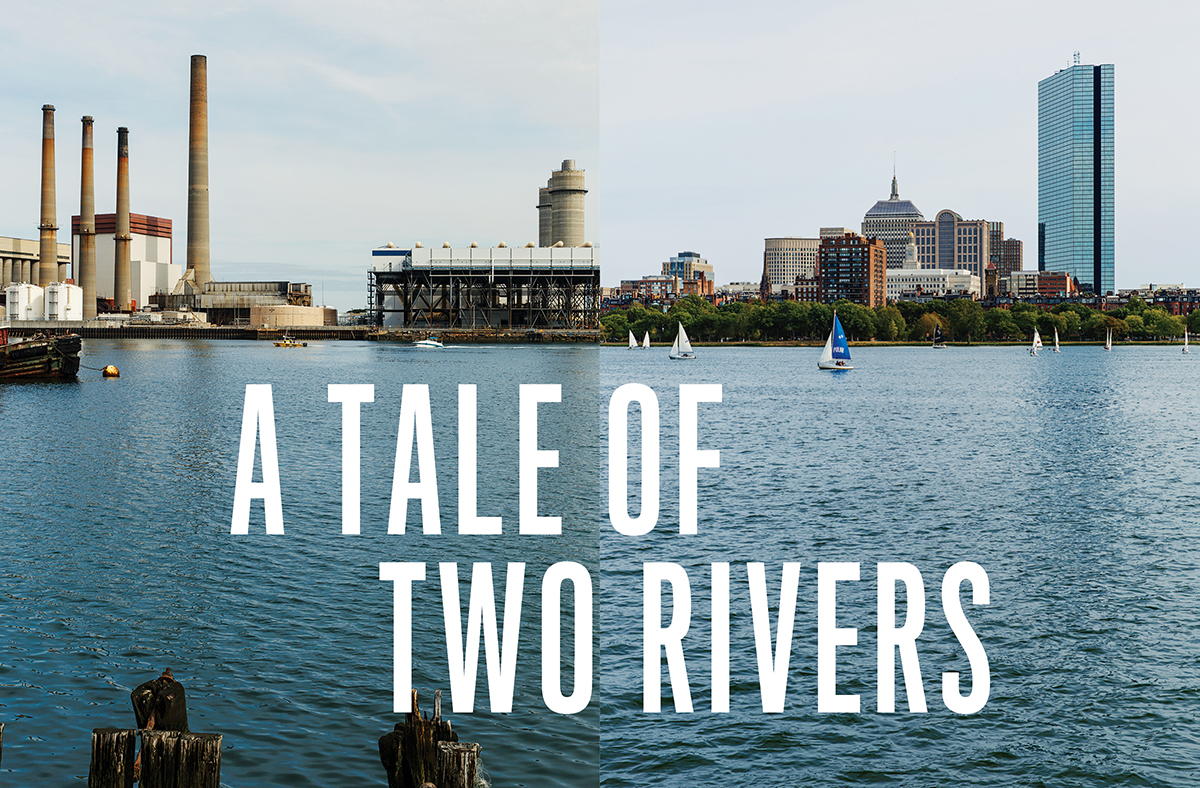

A Tale of Two Rivers

Photographs by Bob O’Connor

The majestic Charles River wasn’t always so majestic. Through the 1980s, anyone who fell into its tea-colored depths was wise to seek medical care and a tetanus shot. Spanning 80 miles from Hopkinton into the lower basin that divides Boston and Cambridge, the Charles ran adjacent to some of our nation’s earliest mills, stockyards, and munitions depots, withstanding centuries of industrial punishment and urbanization. Yet none of that compared with the damage done by antiquated sewer lines and illegal plumbing hookups that funneled billions of gallons of raw sewage into the river. Human excrement, urine, used sanitary napkins, sullied condoms, and anything else that could be flushed down a toilet found its way in there, accompanied by trillions of harmful microscopic bacteria. When the Standells cemented the river into pop culture with the 1966 hit “Dirty Water,” they were actually being quite polite.

Then everything changed. The Environmental Protection Agency spent the 1990s shaming polluters in the press and suing them into submission. The water cleared up quickly, and today the Charles is among the most widely touted environmental rags-to-riches stories in the world. So much so that on a sweltering Tuesday afternoon in July, something extraordinary happened: 278 people jumped into it.

While swimming is not permitted, the Charles River Conservancy had organized the well-publicized dip to show how safe the water has become, and it is urging the city to build a permanent swimming dock near the Museum of Science. As the Boston area experiences its own renaissance, we are in love with the Charles like never before. “I’ve lived on this river or near this river for 20 years, and being in it just makes you feel differently,” said Ed Lyons, a 44-year-old computer programmer, as he dried off near the bike racks. “The river defines the city.”

What about our other famous river, though, the Mystic? Would Lyons take a swim in that? “Uh, no,” he says, followed by a hearty laugh. “I hear there are a lot of cars at the bottom.”

Less than a week after TV news crews captured families splashing around in the Charles, the Mystic River has its own moment in the spotlight when dozens of out-of-towners pile into a bus at PORT Park, in Chelsea. Industrial eyesores loom in every direction. To the right of a basketball court is a 50-foot-tall mountain of salt that will be used to melt snow on the roads this winter. To the left is a commercial dock set against a backdrop of oil tanks. Across the street sits the brick-and-mortar headquarters of Boston Hides & Furs, once deemed a public nuisance by the Chelsea Board of Health and ordered by the feds to pay nearly $1 million to settle allegations of overworking and underpaying its employees. This might seem like an odd spot for a bunch of tourists to kick off a bus tour, but it makes perfect sense if you’re part of a disaster-preparedness conference organized by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

Compared with the Charles, the main body of the Mystic is not very long, running 7 miles. Its northernmost tip, marked by two freshwater lakes, is pristine, with a shoreline dotted by mansions and the Tufts University Boathouse. As you head downstream, the river juts out into half a dozen polluted tributaries, including Winn Brook, in Belmont, which earned an F in water quality last year from the Environmental Protection Agency, and Mill Brook, in Arlington, which earned a D. The scenery along the shore deteriorates in the lower basin as you head past Everett and into Chelsea. Here the Mystic defines the city’s southern border and branches off into two heavily trafficked industrial inlets: Island End River and Chelsea Creek.

“Along the Chelsea Creek we store 70 to 80 percent of the region’s heating fuel and 100 percent of the jet fuel that’s used at Logan International Airport,” says our tour guide, Roseann Bongiovanni, who’s talking over the PA system and pointing out the bus window. As a kid growing up in Chelsea, she says, there were no parks along the shores and the Mystic was just an afterthought, an invisible private-sector workhorse cordoned off by fences and security gates. She didn’t even know her hometown had a waterfront.

Unlike the Charles, a pleasure garden for Cambridge and the Back Bay, the lower Mystic is a playground for polluters. Over the past two decades, episodes have included a 15,000-gallon diesel oil spill from an ExxonMobil terminal; MassPort’s proposal to bury contaminated soil at the bottom of Chelsea Creek; Global Partners’ plan to store carcinogenic asphalt along the shore; and a proposal by Cape Wind’s parent company to put a diesel power plant near an elementary school. “I see a lot of raised eyebrows,” Bongiovanni says, smirking at the skeptics on the bus. “You think this is crazy? This shit is crazy. I kid you not, this happened.”

In light of the Charles River’s remarkable makeover, the persistent onslaught of industrial pollution and development here seems cruelly lopsided. The most heavily industrialized parts of the Mystic are within eyeshot of our beloved Boston Harbor and right in the backyard of some of the city’s trendiest neighborhoods. Eight of the most environmentally overburdened communities in the state are located along the Mystic River Watershed. These places, including Everett and Chelsea, tend to lag far behind their counterparts along the Charles in terms of household income and tend to have higher rates of cardiovascular disease and asthma.

Technically speaking, Everett, Chelsea, and East Boston are classified as “environmental justice communities” and should be afforded special safeguards to counter the decades-long laissez-faire approach to pollution in these working-class areas. Yet to those who’ve been paying attention, it looks like the regulators and legislators who control the Mystic’s fate have thrown in the towel. “Over the years there has been a great deal of attention by officials at the highest level of government toward addressing pollution problems along the Charles,” says Brad Campbell, president of the Conservation Law Foundation. “You haven’t seen any such action along the Mystic.”

How is it that two of the country’s most historical rivers, located just miles from each other, forged such drastically different legacies? On a superficial level, the Charles is the river that Matt Damon crosses on the Red Line to visit his Harvard sweetheart, while the Mystic is where Sean Penn ruthlessly murders an innocent Tim Robbins. But it’s far more than Tinseltown depictions—the rivers’ divergent paths highlight Boston’s deepest, longest-running divides.