How Liberal Professors Are Ruining College

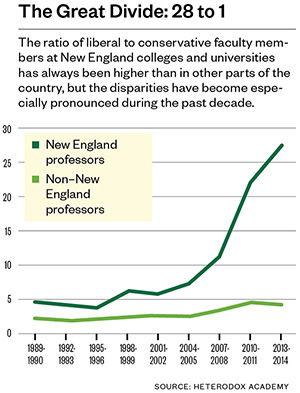

In New England, they outnumber conservatives 28 to 1. Why that’s bad for everyone.

So how did our colleges and universities become such a liberal monoculture—and why is it so pronounced in New England? To this end, Abrams’s research has fueled ample criticisms and theories. Nobel laureate and Times columnist Paul Krugman has argued that professors actually haven’t become more liberal, but rather that the meaning of conservatism has changed and the Fox-ification and now Trump-ification of the Republican Party has pushed highly educated members of the right over to the left. Others contend that it’s solely because conservatives don’t go into academia. There is also the argument that political identities are social constructs that are far too complex and fickle to capture in a simple survey, as well as evidence indicating that the more highly educated a person is, the more liberal he or she tends to be.

Abrams acknowledges that Krugman has a valid point, but says none of these forces is strong enough to explain why the ideological rift in New England widened to the point of 28 to 1. A multitude of factors is at play, Abrams says, including generational displacement. At the college and university level, jobs are rare and don’t turn over as frequently as in many other professions. That means professors from the Silent Generation—those born between 1925 and 1945, who likely cut their teeth as instructors on the campuses of the 1960s—began retiring in large numbers during the early 2000s. In turn, this opened the door to younger, more activist professors, who have since been tenured. It’s no coincidence that the rise of political correctness on campus coincided with the sharp uptick in liberal professors, Abrams says: “It’s all part and parcel.”

On a warm day in the spring of 2014, Michael Bloomberg stood before a crowd of thousands at Harvard and delivered a speech to the school’s 363rd graduating class. Sporting a lavender tie and a light-blue shirt, the Democrat turned Republican turned Independent offered boilerplate platitudes and praise for “America’s most prestigious university.” Several minutes into his remarks, though, he flashed his fangs and began excoriating students, administrators, and professors for fostering a “modern-day form of McCarthyism” that censors speech and muzzles discourse. “Think about the irony,” Bloomberg told his audience. “In the 1950s, the right wing was attempting to repress left-wing ideas. Today, on many college campuses, it is liberals trying to repress conservative ideas, even as conservative faculty members are at risk of becoming an endangered species.”

Bloomberg didn’t single out any specific cases, but one doesn’t have to look very far to find examples that help explain why a man who champions a number of progressive causes—contributing millions to Planned Parenthood and funding research for tighter gun-control policies—used his platform as Harvard’s commencement speaker to shed light on the shifting cultural norms on campus. Earlier in the school year, students at Brown University had protested and compelled administrators to cancel a lecture by New York Police Department Commissioner Ray Kelly, a registered Independent and the architect of a failed stop-and-frisk program that disproportionately targeted minorities. “Discourse facilitated, legitimized, and moneyed by the few in power is not true ‘discourse’ at all,” then-Brown student Doreen St. Félix wrote in the Guardian, defending the protests. Then, at Smith College, the all-female school in Northampton, the International Monetary Fund’s Christine Lagarde—called “one of the most accomplished and powerful women in the world” by the Washington Post—was forced to cancel her commencement speech after faculty and students took offense at certain IMF lending policies. Today’s college progressives “don’t simply think you’re wrong, they think that you’re dangerous,” says Christina Hoff Sommers, a resident scholar at the conservative American Enterprise Institute. “I might agree if they were talking about someone way out on the fringes, but they’re talking about Republicans and Libertarians.”

The examples go on forever, and are not limited to students upset with guest speakers. In one of the more widely cited instances of campus PC culture gone haywire, the Asian American Students Association at Brandeis put up signs meant to teach students about microaggressions against Asians, which included slogans such as “Aren’t you supposed to be good at math?” Another group of Asian-American students took offense, deemed the exhibit itself to be a microaggression, and demanded that it be removed. The student president of the group that put up the posters ultimately apologized in a campus-wide email, expressing sympathy for classmates who felt injured by the exhibit.

Brandeis, among the 35 most competitive universities in the country, was founded in 1948 and named for the first Jewish Supreme Court justice, Louis Brandeis—a man deemed by his successor as “a militant crusader for social justice.” Since the university’s founding, social justice has remained at the heart of its educational mission and a pillar of the curriculum. Like many universities, though, it has struggled in recent years to accommodate the heightened sensitivities of students without infringing on personal freedoms. Brandeis is not without conservative students, but those on the right are admittedly fearful of sharing their views.

At the start of the fall semester, the Brandeis Hoot, one of two campus papers, asked 509 students a series of questions: How do you identify politically? How comfortable are you sharing your political views on campus? And why are you hesitant to share, if applicable? Of the 13 percent of respondents who identified as conservative, three-quarters said that they chose not to express their political views on campus. Some feared verbal attacks from classmates; others didn’t want to be harshly judged by professors. “Politics is something I don’t talk about with many people at all because of the ramifications,” says Mark Gimelstein, a senior at Brandeis and president of Brandeis Conservatives. A small campus group, it drew a handful of attendees to the weekly meetings I sat in on throughout October. None supported Trump; one student present was a liberal who kept showing up because he enjoyed the conversation; and several other members leaned more libertarian than conservative.

Gimelstein describes himself as a “conservatarian,” someone who favors small government and fiscally conservative policies. When it comes to social issues such as gay marriage, he says, the federal government should stay out of them. As for the alt-right, he says, “I think my last name gives it away—Gimelstein wouldn’t be welcomed.” To be openly conservative on campus, many members of the conservative club agree, requires thick skin. “People mock us,” Gimelstein told me, claiming that roughly half the students who approached his club’s table during a sign-up event scoffed at the notion that Brandeis even had a club for conservatives.

Gimelstein speaks highly of the quality of education he’s received, but says there is an undeniable liberal slant among his professors that has ranged over the years from annoying to detrimental. “My intro to microeconomics course, I won’t name the professor, but he literally yelled that he hated Republicans in class,” Gimelstein says. Though it was intended to be more humorous than mean-spirited, it had a chilling effect. “While all my classmates were laughing along, I wasn’t laughing,” he says. “It was kind of insulting and it made it harder to have a productive conversation.”

Michael Musto, a Brandeis senior who is a double major in politics and history, has seen similar events play out in class. When the influential conservative Phyllis Schlafly died this past September, Musto recalls, one of his professors quipped, “There’s a special place in hell for people like her.” A month later, when Tom Hayden, a co-author of the Port Huron Statement and founder of the Students for a Democratic Society, died, the same professor eulogized Hayden’s contributions to the left. “The average student who is just trying to study gets the impression of, ‘Oh man, those evil right-wingers,’” says Musto, who identifies as a Libertarian. Frustrating as it is for him, Musto keeps a low profile for fear of being that guy in the eyes of the person who will be grading his papers. Like other Brandeis conservatives, he says, “I never really speak up.”

Brandeis president Ronald Liebowitz, who previously served as the president of Middlebury College, in Vermont, is troubled by the notion that conservative students are reluctant to express their views in the classroom. During his 30-plus-year career in higher education, he has heard concerns of liberal bias play out time and again. At both Middlebury and Brandeis, parents and alumni have told him that they wanted to see more ideological balance among the faculty; some suggested going so far as to impose an ideological litmus test during the hiring process to ensure a greater diversity of viewpoints. Liebowitz isn’t keen on the idea. “I think what we have to do instead,” he says, “is ensure that the classroom does not become politicized.” As for Musto’s and Gimelstein’s stories about professors poking fun at Republicans, Liebowitz says these comments don’t rise to the level of suggesting an adversarial environment for conservatives at his university. “I would think that Brandeis students, Middlebury students—smart students—would have the mettle, the ability to question this or push back a little,” he says.

Many people argue that a professor’s bias, to the right or the left, does not affect the quality of instruction or mean that students are receiving a one-sided education. But as Musto and Gimelstein point out, that’s giving little credit to students who are trying to learn in an atmosphere where to be liberal is to be in on the joke, and to be conservative is to be the punch line.