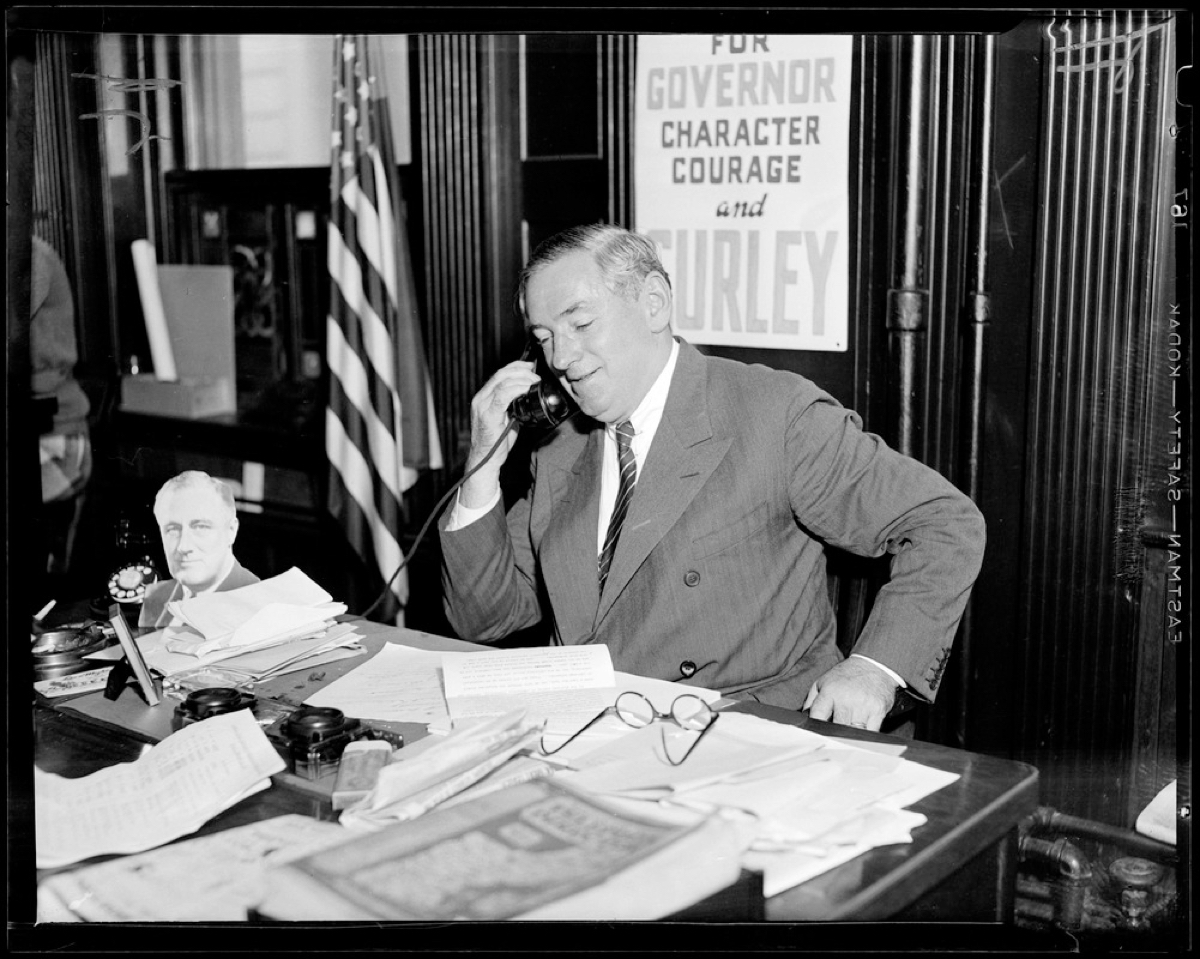

Gov. James Michael Curley Was the Prototype for President Trump

Photo via Jamaica Plain Historical Society/Creative Commons

Today’s Bostonians are likely better acquainted with the Downtown Crossing watering hole that bears his name than James Michael Curley himself. And if they have heard his name, it’s because someone gave context to the oft-parroted fact that an incumbent mayor of Boston has not lost reelection since 1949. It was Curley, fresh off a jail stint for mail fraud.

He was more than a four-term mayor. Curley was a ward heeler, party boss, state representative, a four-term congressman, and, in a strange turn of events, Puerto Rico’s delegate to the 1932 Democratic National Convention. (The newspapers dubbed the proud Irishman “Don Jaime.”) However, it was Curley’s single term as governor of the Commonwealth that proved his most disastrous—and bears striking resemblance to the frenetic, fledgling presidency of Donald Trump.

“When he took office as Governor, he carried with him the highest hopes of Boston and Massachusetts,” the Boston Post wrote. “How he maltreated those hopes is one of the blackest pages in the chronicle of the public life of any man in the history of the Commonwealth.”

Curley set his sights on Beacon Hill in 1934 against the backdrop of the Great Depression. Just as Trump made enemies of the sacred cows of the Republican establishment, Curley kicked off his campaign outside a defunct hotel in the Financial District—sans slow escalator ride—calling the Democratic governor, senator, and state party chairman “the Hitlers of the Massachusetts Democracy” and “three card monte men.”

Like Trump, he rode to office swaddled in scandal. The Boston Finance Commission was fast uncovering various cases of graft during Curley’s time as mayor. As governor, he would have the power to cripple the watchdog body and avert a serious investigation by stacking it full of cronies. For his own sake, he needed to run for governor.

The giant floral arrangement Curley received after his January 3, 1935 inauguration was still fresh by the time he began hacking away at the state’s organs of oversight. The cold celerity of Curley’s housecleaning bears resemblance to Trump’s swift and unceremonious dismissal of acting Attorney General Sally Yates, who refused to defend his controversial Muslim travel ban.

Former Gov. Alvan T. Fuller, no friend of Curley’s, told the Worcester Telegram that his vocabulary was “too limited to describe the depths of infamy to which the affairs of Massachusetts have sunk.”

Like Trump, Curley enjoyed a close relationship with his daughter, Mary. And just as Ivanka Trump’s husband Jared Kushner has consolidated power inside the White House as a senior adviser, Mary’s husband Edward Donnelly (like Kushner, a Harvard alum) used his proximity to the Guv for personal benefit.

The CEO of a major Boston outdoor advertising agency, Donnelly “was the state’s billboard king,” wrote author Jack Beatty in The Rascal King: The Life And Times Of James Michael Curley. It was hardly a coincidence when, as Mr. and Mrs. Donnelly enjoyed their honeymoon, Gov. Curley filed a bill before the legislature that wrenched authority away from cities and towns to veto the placement of billboards and delegated it to a state advertising czar, appointed by the commissioner of public works—a Curley appointee.

By year’s end, a Donnelly electric sign stood in front of the State House.

Curley with his daughter Mary. Photo via Jamaica Plain Historical Society/Creative Commons

“There is only one political party in the Commonwealth at the present time—and that’s the Governor,” Curley notoriously declared. But halfway into his two-year term, Curley sat in the desk chair gifted to him by Benito Mussolini and watched as down-ballot candidates across Massachusetts got walloped. A mayoral candidate in Worcester, for example, suffered a dramatic upset thanks in no small part to the hulking eyesore of a Donnelly billboard in town.

“The fight to terminate misrule in Massachusetts has just begun. I shall continue it unceasingly until the people have retired this man who would outdo Hitler in private life,” said Boston Mayor Frederick Mansfield.

Trump has made the return of long-departed manufacturing jobs a top priority, and through no shortage of theatrics—his pre-inauguration publicity stunts with Carrier, his Twitter shaming of companies like Toyota and Ford—has conjured the appearance of making progress to this end. But just as Carrier plans to use the millions in taxpayer subsidies it received to further automate the plant Trump claimed to save, and more companies recycle their old news of U.S. job creation to placate the president, Curley’s crusade for “work and wages” was, as the saying goes, all sizzle and no steak.

Curley boasted on the campaign trail that his relationship with President Franklin D. Roosevelt would help him secure federal grants and New Deal projects for the Bay State. Unbeknownst to voters, FDR’s capos couldn’t stand him, and routinely ignored his requests.

“Times without number the Governor has descended on the President, accompanied by his glittering staff with fanfare of trumpets, demanding money for some whimsical purpose which intrigued his fancy at that moment,” Fitchburg Mayor Robert E. Greenwood told the Globe in August 1936, “and no matter how much or how little—and mostly how little—success he might have had, he immediately gave statements to the newspapers regarding nonexistent promises of fabulous amounts.”

With his second and final year in office came more vicious diktats—chief among them, a proposal to require all state judges aged 70 and older to appear before psychiatric professionals, elected officials, and Curley himself to test for signs of senility. If they couldn’t pass muster, they would be forced to retire. Such contempt for the judiciary comes naturally for autocrats.

SEE YOU IN COURT, THE SECURITY OF OUR NATION IS AT STAKE!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) February 9, 2017

“Please will the people of Massachusetts read Sinclair Lewis’ It Can’t Happen Here. It can happen—it is happening,” the Holyoke Transcript pleaded. The 1935 novel, which details a authoritarian fascist’s rise to power in the United States, sold out following Trump’s victory, and remains the 20th most-purchased book on Amazon.

The mental exhaustion induced by the Trump administration’s dizzying flurry of outrages can claim a forebear in the exasperated disbelief that observers of Curley’s reign held for the farrago of “things that made the government of Massachusetts ludicrous part of the time, shocking most of the time, and tawdry all of the time,” the Herald noted. It only ceased once he unsuccessfully sought a Senate seat in 1936, losing to Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. For Trump, there is no higher office.

To be sure, the comparison between “The Donald” and “The Curley” isn’t a wholly perfect one. Brought up in penury, Curley was a self-made man, irrespective of the legality of the means with which he obtained that new wealth, and a career politician. He was an autodidact who delighted in the classics and loved to quote Shakespeare, while Trump, per reports, prefers Morning Joe to Macbeth.

And while the two men differ on their attitudes about immigration, both used the issue to their political advantage. Curley curried great favor among Boston’s immigrants, who, time after time, carried him to office. Inversely, Trump exploited xenophobic anxieties to successfully court the white, working-class voter.

Yet Trump, who rushed to the golf course just two weeks into his presidency, would be wise to avoid the example set by Curley, who used state troopers for his caddies.