Toy Story

photograph by Jarrod Mccabe

Mixed-media artist Richard Whitten inhabits a unique reality, one in which dreams transcend from dark corners of the mind and emerge in vivid color on 3-D panels like windows to another realm. “You have this transition from our world into the imaginary space,” he says of his paintings and mechanical sculpture, which will be on display at the Dedee Shattuck Gallery, in Westport, come September. Calling to mind vintage Tivoli game boards, Whitten’s work acts as a peephole into a labyrinth of possibilities, “like Alice in Wonderland reaching her arm through trying to get into the garden,” he says.

Whitten’s use of perspective beckons viewers to gaze as if through a keyhole into a physically perplexing space: winding staircases to nowhere, and grand, curving corridors. His pieces—which feature architectural details hailing from the Baroque and Rococo periods as much as from the Island of Misfit Toys—culminate a lifelong exploration of implied motion and animate objects. As a teenager, Whitten crafted model airplanes from balsa wood, mylar, and wire—a hobby that he says also led to his recent experimentation with toy-sculpture construction. “I’m buying a whole lot of weird things all the time now,” he says: Nylon washers and bearings, fly-tying materials, fishing weights, snippets of tin, spools, gears, and escapements from old clocks all show up repurposed in his mechanical sculpture. “I actually don’t want people to recognize the materials,” he says. “I don’t want them to say, ‘Oh, look! He’s turned a spool into a pig.’ They’re not supposed to look folksy.”

Whitten, a graduate of Yale and UC Davis, brings his haunting painted visions to life in a spacious Rhode Island studio of his own design (he even crafted an adjustable counterweighted easel, modeled after Renaissance altarpieces, that spans the back wall), situated behind his majestic late-19th-century Arts & Crafts–style house. The carefully curated interior of the home, decked out with intricate dark moldings and a curious collection of antiques, is a fitting place to display and conceptualize his artwork. A drawing room in a second-level turret overlooking the front yard, for instance, does double duty as a home for Whitten’s collection of vintage ice-fishing lures. “I stopped collecting them when they started selling for hundreds of dollars on eBay,” he says.

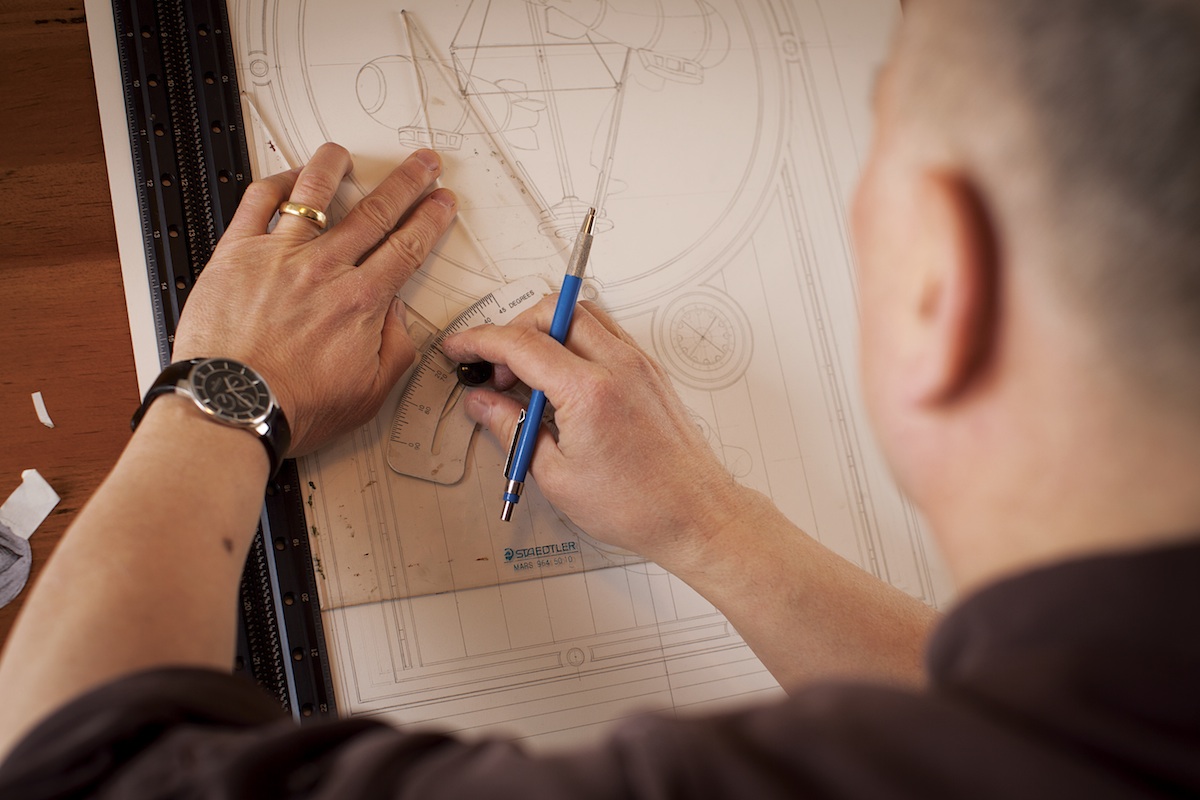

Strange yet compelling objects like these inspire Whitten’s inventive work. He allows ideas to gestate for several years as they develop from initial thoughts into sketches rendered in the scores of notebooks he stocks full of intricate doodlings. The shape for the cat-and-mouse paddles seen in Thaumatrope, Cacchia, and others, for example, was born from a small mirror Whitten saw while visiting the Estruscan Museum, in Italy. “Every once in a while you go back through your notebook and say, ‘That’s an interesting idea—what can I do with that?’ Then you need another sort of quiet period to work it out,” he says. The next phase is drafting, which is followed by building the panel out of birch ply and maple.

Whitten chooses the paints he uses as carefully as he decorates his home. While he says he’ll use “whatever has the best pigment,” he often finds himself returning to Old Holland, Williamsburg, and Vasari Classic Artists’ paint, which is made by hand in small batches in New York. Most paintings take about two months to complete before a museum-quality varnish is applied.

Whitten views his finished work as both a semblance of life and an object of desire just out of grasp. “Many are about the passage of time at different speeds,” he says, “while others are about an instant in time as opposed to a timeless moment.”

photograph by Jarrod Mccabe

The painting Funambuliste.

PHOTOGRAPHS BY JARROD MCCABE

Whitten keeps a variety of paint on hand at all times; the artist poses in his Rhode Island studio; vibrant toy balls appear in almost all of Whitten’s paintings.

photograph by Jarrod Mccabe

Large completed works are stored in the studio loft when not on display at a gallery.

PHOTOGRAPHS BY JARROD MCCABE

A mechanical sculpture in the spirit of the painting Funambuliste. Whitten often mixes his own pigments using fine handmade oil paints.

photograph by Jarrod Mccabe

Many of the forms in Whitten’s sun-filled drawing studio show up in his work.

photograph by Jarrod Mccabe

Whitten frequently returns to the same shapes or objects—here, he sketches the blimps from his painting Augenblick, a German word for “moment.”