Ben Mezrich: Based on a True Story

Photograph by Guido Vitti

In the movie, the professor will be played by Kevin Spacey. Ben Mezrich is thrilled with this, and with everything else about 21, the forthcoming cinematic adaptation of the book that made him a star. He can’t wait to show off the new paperback cover that will be rolled out in conjunction with the film’s release. There’s a mockup of it splayed out on his coffee table, right next to a case of promotional casino chips stamped with the 21 logo.

The author sits in his lavish Back Bay apartment, arms spread across the back of his couch. Behind him, just past the balcony, is a spectacular view of Cambridge and the Charles. Six years have passed since the release of Bringing Down the House: The Inside Story of Six MIT Students Who Took Vegas for Millions. The book spent more than a year on the New York Times bestseller lists, and there are now more than 1.5 million copies in print in 12 languages. It’s the work Mezrich is known for, the force behind the wave of success he continues to ride today. And with this month’s release of the big-screen version (which also stars Laurence Fishburne and Kate Bosworth), Mezrich figures he can look forward to all kinds of new book sales. And attention.

As well as his book has done, the 39-year-old has become even better known for his embrace of the fast life. At a recent launch party for his latest tome, Rigged: The True Story of an Ivy League Kid Who Changed the World of Oil, from Wall Street to Dubai, the ambiance was fitting: dark, but not too dark—as though the light dimmer was set on “mood.” Music thumped through the speakers, and women with cleavage on full display pressed against men working hard to look casual. Mezrich was dressed up, as always, in his image of a bestselling author: frosted spiky hair; white dress shirt with a few buttons undone, allowing chest hair to peek out and say hello; collar resting atop a blue smoking jacket; designer jeans; white shoes that could have come straight from Tom Wolfe’s closet. The event had been scheduled for a smaller venue, but was moved to 33 on Stanhope Street, his publicist bubbles, “because of overwhelming response.” It seems everyone wants to be around Mezrich these days.

Indeed, Mezrich’s world couldn’t be more different from what it was before BDH. One day he was in Boston, a middling novelist wondering whether his first attempt at nonfiction would sell; the next he was on the Today show, telling America all about his incredible yarn. And that was just the start. He found himself attending bashes at the Playboy Mansion. He got to ring the bell at the Mercantile Exchange in Manhattan, was invited to host World Series of Blackjack for the Game Show Network, and did a few episodes of a show on Court TV. Mezrich used to joke that while most writers want a Pulitzer, he simply wanted to be named to People‘s sexiest list. Then, after BDH came out, he was.

Half a decade later, the momentum has barely slowed. Ben Sherman, the clothing company, now sends him boxes of free shirts, pants, and shoes, adopting him as a walking billboard. Maybach, the luxury car line, recently brought him down for a party in Miami. His standard fee for speaking engagements has grown to $20,000. Mezrich, in other words, has created for himself an existence every bit as unbelievable as the stories he writes.

“We love being in the Ben Mezrich business,” says Spacey, who is developing two other Mezrich books into movies. Mezrich loves it, too. “I have this crazy lifestyle,” he says. “I mean, every week there’s something I’m invited to. It’s pretty cool.”

It’s rare, what Mezrich is doing. A few decades ago, the cultural landscape included plenty of celebrity authors—Capote, Mailer, Wolfe, oversize personalities celebrated as much for their personal excess as their literary excellence. No longer. As books have been choked off in favor of digital cable and the Internet, the fame once afforded authors has shifted to reality TV stars and whichever attention-starved, coked-up anorexic manages to leak her sex tape.

“My heroes, like Hemingway, he was a personality as much as a great writer,” Mezrich says. “The goal for me is to be an entertainer and a personality—Hunter S. Thompson, minus the drugs and the guns and the suicide. He was what he wrote. To some extent, I am what I write, too. I write about kids living this high life, and I do it, too.”

Mezrich has written three books since Bringing Down the House was released in 2002, and, just like BDH, each of them features smart young people who do amazing things, beat long odds, make obscene money. Invariably, his protagonists face a daunting challenge—usually in the form of seedy, unscrupulous foes who try to orchestrate the heroes’ demise, leaving them to determine how far into the muck they’re willing to wade. The stories can all be distilled down to the trademark “Mezrich marketing sentence,” a line on the cover that quickly summarizes the drama awaiting inside. For Busting Vegas, it was “the MIT whiz kid who brought the casinos to their knees.” For Ugly Americans, “the true story of the Ivy League cowboys who raided the Asian markets for millions.” They are the hooks that reel in twentysomething hustlers—his most eager readers.

Mezrich’s friend John D’Agostino met one of them once in Miami. The South Beach nightclub promoter went crazy when he learned that D’Agostino knew Mezrich. The guy had read all of Mezrich’s books. “This is a perfect example of a guy who loves Ben Mezrich,” D’Agostino says. “Young kid. He grew up with kind of a bad life. Was not well educated, but really ambitious. He had, like, four businesses going. And Ben is like his freakin’ prophet. He basically models his life after the characters Ben writes about.”

There’s a blueprint for both what Mezrich writes and how he writes it. He locks himself in his apartment (actually, his other apartment—he has two units in the same high-rise, one of which serves as his office) and hammers out a book in two or three months. It’s a dizzying pace. But that’s how he did it with BDH, and he’s taken care to follow the recipe with his subsequent tales.

“I’m not looking to use big words,” Mezrich admits. “I write for people who if they weren’t reading my book, they wouldn’t be reading another book. They would be watching TV. I’m not competing with other books. I’m competing with the Red Sox.” Mezrich works hard to build the excitement early in his plots, before attention spans wane. He gets right to it in Rigged, explaining in the first few pages the main character’s involvement with the shady world of the New York Mercantile Exchange: “If Wall Street was the financial equivalent of Vegas, the Merc was Atlantic City—on crack.”

Not exactly Hemingway. But then, that’s not exactly the point.

During his college years at Harvard, and even for a long time after, Mezrich was a touch quiet and socially awkward. He had a haircut that his wife, Tonya, describes as a “Lego piece,” a helmetlike ‘do that looked like it could be removed all at once. He also had a “go-to” shirt—an off-white number with stripes and stitched designs that looked like crop circles—that popped up in pretty much every photo he was in for about five years. Mezrich is not a terribly big guy—really, very average and nondescript—and when he went out to a bar, he was perfectly happy to hide in the background. One night, he saw a beautiful girl across the bar, but he was too nervous to approach her. He sent a friend over instead. That’s how Mezrich met Tonya.

“He was a total geek,” D’Agostino says. “He had this huge TV with a PlayStation. He was really into sci-fi. He was really nice and quirky. He was writing about nanotech, and his room was like a fucking hurricane hit it. There were nanotechnology books everywhere.”

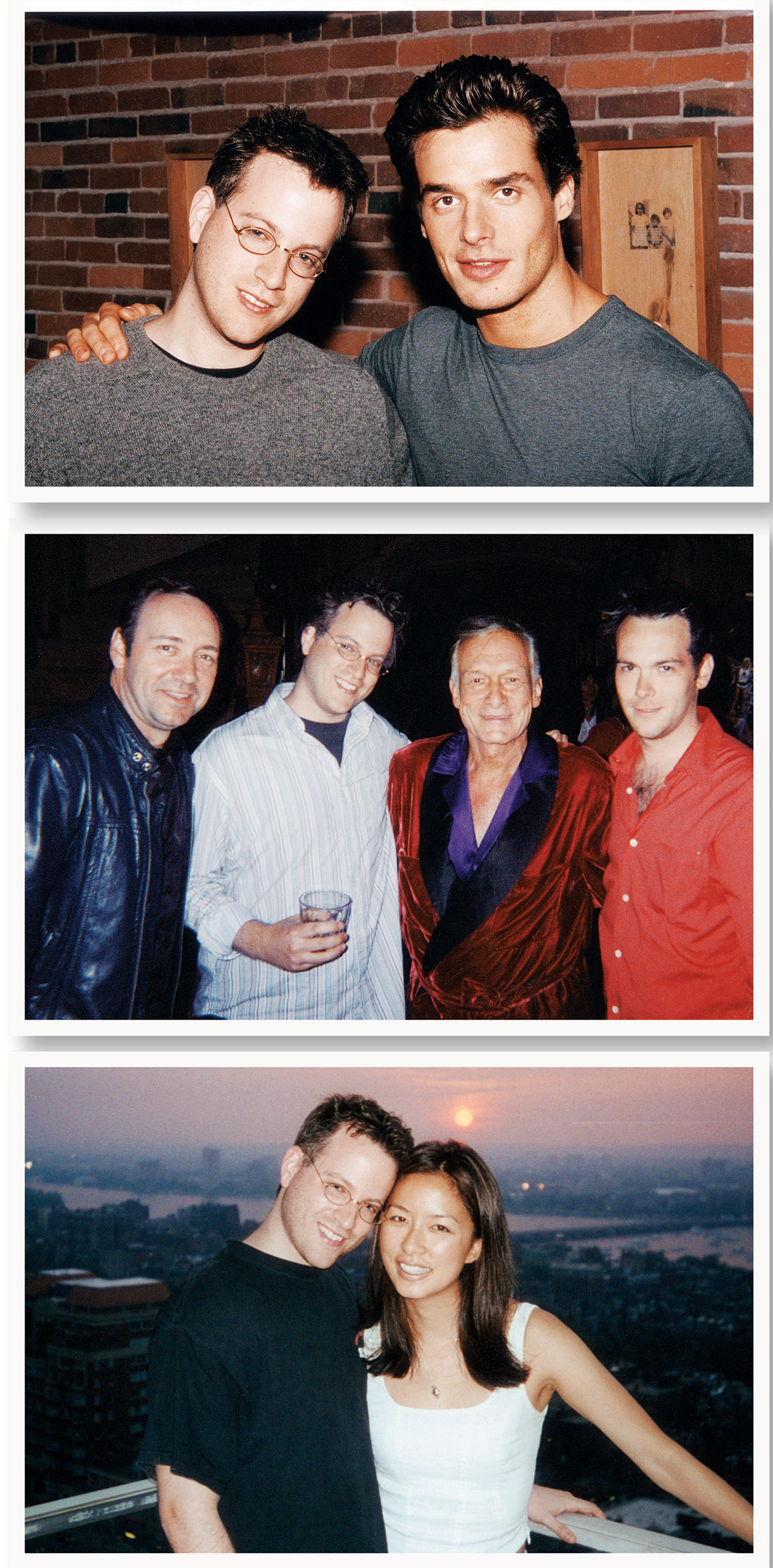

Mezrich in a signature pose with, from top, Antonio Sabato Jr.; Kevin Spacey, Hugh Hefner, and Spacey’s business partner, Dana Brunetti; and wife Tonya.

Mezrich had done some writing for The X-Files after college, but mostly he was scribbling novels. The first few were never published. Mainly because they weren’t good. “They were crap,” Mezrich corrects. “I sent them out—reject, reject, reject. I got about 190 rejection slips. I still have them.”

At the time, he was doing some of his writing under a pen name that wasn’t much better than his prose: Holden Scott, a mash-up of the Catcher in the Rye protagonist and the Great Gatsby author. Luckily for Mezrich, while he was developing his career, his parents were willing to offer some support. His mother, Molli, had always thought her son would become an author, remembering how, when he was six or seven and growing up in Princeton, New Jersey, he would sit on the stoop outside a relative’s house and occupy himself with a pencil and paper. “He’s been a storyteller for a long time,” she says.

His dad, Reuben, agreed to send money to cover the bills. But he wanted Mezrich to find solid work. Paying work. “I was worried that this guy would be living in a cardboard box,” he says, recalling his son’s unpublished works. “To be honest, his earlier books weren’t so hot.”

Still, Mezrich kept knocking them out, rushing water against the dam. Maybe as he did so, he got better. Maybe it was luck. Whatever the cause, he finally managed to get his first novel published in 1996. It was a thriller called Threshold that somehow wove together a mad scientist, the mapping of the human genome, and the unexpected death of the secretary of defense. Next would come the novel Reaper, which was turned into the TV movie Fatal Error, starring Antonio Sabato Jr. and Robert Wagner. “It still airs on the Sci Fi Channel,” Mezrich says. “It’s really a piece of shit.”

Four more novels followed over the next two years. They sold well enough that his parents no longer had to prop him up, but not so well that anyone knew who he was. The night that he worked up the nerve to speak to Tonya, she asked what he did for a living. He said he was an author. She assumed he was lying.