Over His Dead Body

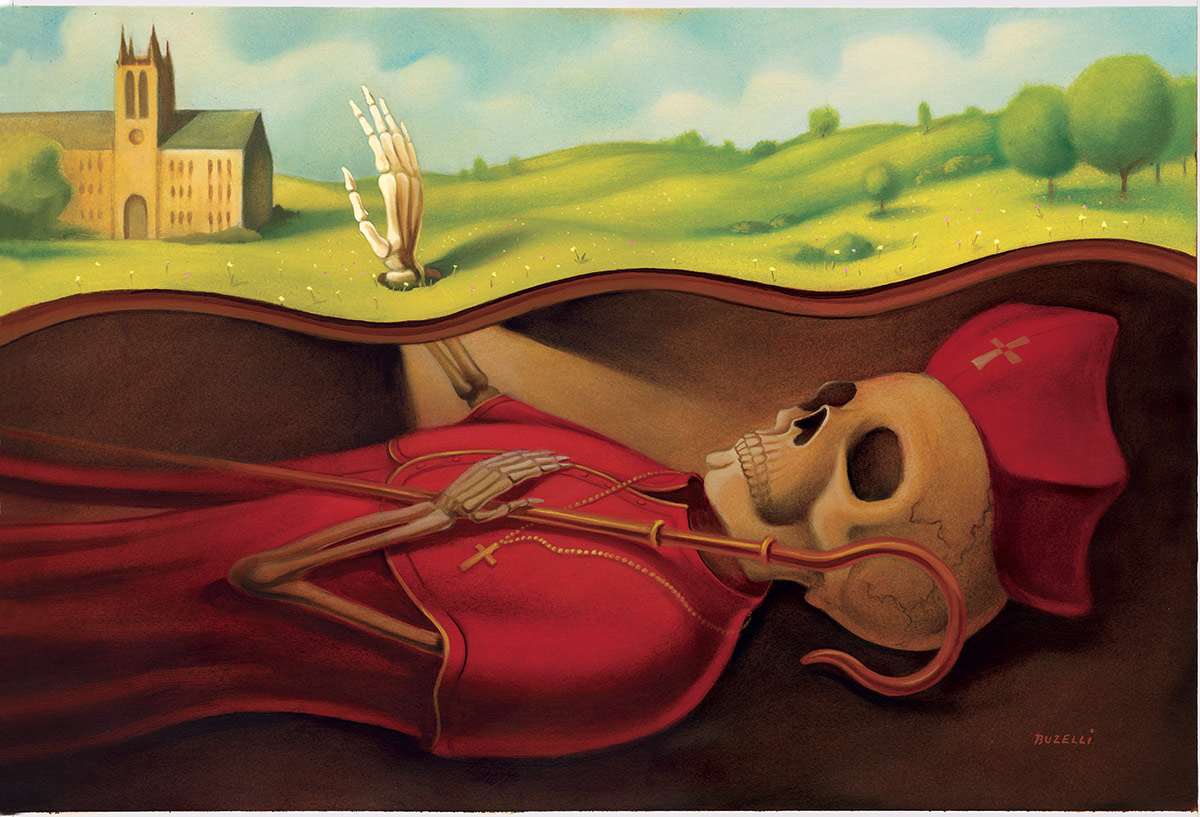

Illustration by Chris Buzelli

Follow Commonwealth Avenue deep into Brighton, past the beer-soaked Boston College student tenements that funnel down to Cleveland Circle, and slow at the verdant, sprawling expanse that opens up after Greycliff Road. Now look to your right, to the 65-acre St. John’s Seminary-Chancery complex that runs north from Commonwealth for half a mile alongside Lake Street’s august Colonials. The seminary’s stone halls sit shrouded in trees near the property’s far edge. But it’s another building—the four-story, 23,000-square-foot cardinal’s mansion—that dominates the landscape.

Now look behind the mansion, where the ground swells, rising to a hilltop that overlooks the complex and, in fact, all of Boston. On that hilltop is a mausoleum, with rusted gates and busted glass doors that open to a Gothic tomb covered in bird dung. Deep under the floor of this shrine, guarded by stone angels and lions, lie the remains of Cardinal William Henry O’Connell. Down there—that’s where this story really begins.

O’Connell was a sizable man, and he ruled the archdiocese from 1906 until his death in 1944 with a domineering personality. He was the first Boston Catholic leader to command the city’s attention, due in no small part to the confluence of his tenure with a huge influx of Irish immigrants. O’Connell was ruthless; he had come to power by directly politicking the Vatican. But the masses loved him. His elevation to cardinal in 1911 spurred weeks of local celebration and breathless coverage in the newspapers, and was seen as confirmation that Boston had at last become one of the world’s great cities. Reporters trailed him constantly, and anything he uttered was news, just because he had said it.

O’Connell was hyperconscious of his image and, accordingly, had a better understanding of the press than his contemporaries did. He seized control of the Pilot, then an independent Catholic newspaper, and turned it into the official archdiocesan organ it remains today. He wasn’t above making up news, either. In 1915, O’Connell published letters collected from his formative years—as men of his stature were wont to do—to predictable fanfare. Some, though, suspected the cardinal had fictionalized his youthful correspondence. That assumption turned out to be true.

Politically, O’Connell held such clout that members of the state legislature referred to him as “Number One.” The mere intimation of his backing, whispered about though never confirmed, was enough to incite a stampede of support that swept Maurice Tobin past James Michael Curley in the 1937 mayor’s race. O’Connell plainly enjoyed the spotlight, and refused to share it. When both he and Governor Curtis Guild were invited to one reception, he bluntly told the event’s organizers, “You must choose between the governor and me.” The governor was promptly uninvited.

Such a man could not live in anything but opulence. Even before he was made cardinal, O’Connell had his allies raising funds to move him out of the archbishop’s cramped apartment at the Cathedral of the Holy Cross in the South End, where streetcars rumbled and vandals lurked, and into a house in the Back Bay, then one on Fisher Hill in Brookline, before finally withdrawing in 1927 to Brighton and the dignified environs of St. John’s Seminary. The church constructed the Commonwealth Avenue mansion for him, and O’Connell brought along the archdiocese’s administrative offices, which were housed in facilities built in a grand Renaissance Revival style that evoked Vatican architecture. O’Connell’s own little Rome.

His new home did more than assuage his ego. It was, above all, a message to Boston’s Brahmin elite. The city’s teeming Catholic masses were to be respected, now that they—or at least their leader—could live as well as their Protestant counterparts. “The Puritan has passed,” O’Connell spat during one sermon. “The Catholic remains.”

Control of the property also allowed O’Connell to settle an old score. St. John’s, you see, was being run by the Sulpicians, a French priestly order, when O’Connell began direct oversight of the complex. His grudge against the order went back to his own days as a young seminarian at St. Charles’s College in Maryland, where he had spent two miserable years chafing under the Sulpicians’ discipline before the order ultimately declared him unfit for the priesthood. After returning to Boston and enrolling at BC, O’Connell never forgot that snub. He was quick to use his position as archbishop to evict the order from the seminary.

In 1928, O’Connell built the shrine atop the chancery grounds. Although he consecrated it to the Virgin Mary, he intended it more as a memorial to himself, and made plans to be buried there—a riddance to the archdiocese’s tradition of interring archbishops in the Cathedral of the Holy Cross, a final resting place not nearly regal enough to hold him. And so it is today: the cardinal’s eternal gaze fixed on the seminary he remade in his own image, overlooking the city he ruled for 38 years.

In a way, it’s a city where even now O’Connell holds a lot of sway. Because while he lies there, forgotten by most of us, a tempest is swirling over his remains, one with more than $1 billion in big plans, and the fate of a neighborhood, riding on its outcome.

Let’s return briefly to our tour. Across the street and a block to the west of the seminary grounds sits Boston College. The school wants to expand. It believes it has to expand. So when Archbishop Seán O’Malley was hard up for cash a few years ago and looking to dump land to remain solvent, BC introduced itself as a willing buyer.

Two problems with this transaction. Number one: When BC bought the archdiocese’s land, it bought what’s left of O’Connell, too. His family doesn’t want to see its “Uncle Cardinal” moved, and points to the cardinal’s will as proof that he didn’t want to go anywhere. Problem number two: the fuming Lake Street residents.

Lake Street, remember, slopes down the western edge of the former archdiocesan land. Its homeowners long ago grew used to the quiet the archdiocese kept. They don’t want loud, drunk college kids moving in. It hurts property values, and just imagine it in the winter: students looking from their shiny new dorms through the bare trees and into the living rooms—or bedrooms!—of the grownups across the street.

As it happens, one of these angry neighbors is Secretary of State William Galvin, who lives at number 46. He’s opposed as a private citizen to BC’s expansion plans. Worse for the school, Galvin’s professional obligations include ensuring that the state’s historical sites (read: the seminary) stay historical.

One way—a myopic way—to gauge what we have here is as another town-gown real estate spat, like Harvard bulldozing all of Allston. But really, here in this corner of Brighton is a battle royal among the most important forces in town: the Catholic Church’s interests; the government’s maneuverings; academia’s pretensions; property owners’ rights; and history’s long, long reach and relevance. It’s a fight that could take place in no other city—and fights like those, of course, tend to be the juiciest kind.

O’Connell’s elevation to cardinal set a powerful precedent. Each of the four Boston archbishops who’ve succeeded him has been named one as well. Thanks to O’Connell, the position has become Boston Catholics’ birthright, and he ensured that it would remain highly potent for his successors.

“It wasn’t just about being the leader of one of the churches in the area,” says O’Connell’s biographer, Boston College historian James O’Toole. “He made the archbishop a public figure comparable to the mayor or the governor.” Cardinal Richard Cushing’s advocacy on behalf of the working class and the Kennedy dynasty, Cardinal Humberto Medeiros’s public management of the busing crisis, and Cardinal Bernard Law’s political activism on abortion, the death penalty, and Cuba—they all followed the model established by O’Connell.

There are darker parallels, too. O’Connell presided over a system of archdiocesan rule that valued prestige and personality politics above everything else while ignoring the sexual misconduct of its underlings. Two of O’Connell’s closest aides, both of whom lived with him in the cardinal’s residence, were married at the same time that they were serving as ordained priests. One, his nephew James O’Connell, kept a wife in New York and was believed by O’Connell’s enemies in the clergy to be embezzling archdiocesan funds to pay for this arrangement. The second, Father David Toomey, edited the Pilot and served as the cardinal’s personal chaplain. His secret marriage to a Manhattan woman, done under an assumed name, was part of a bigger double life: When the Manhattan wife visited Boston, she found Toomey having an affair with a Cambridge girlfriend. Toomey and James O’Connell were also known for hosting bacchanal dinners for favored clergymen. A dissident priest reported that one such affair featured indecent menu cards and “enough liquors to float a battleship.” O’Connell’s enemies frantically lobbied church leadership in Rome to have the cardinal removed from power in Boston and transferred to an obscure ceremonial post, but the Vatican was unswayed.

This imperviousness to the rule of man, 50 years after O’Connell’s death, also informed Cardinal Bernard Law’s reign, of course. But 21st-century society hit back, and the cardinal’s complicity in the sex abuse scandal invited the massive lawsuits that nearly bankrupted the archdiocese. As it scrambled for ways to settle its mounting debts, Law’s replacement, Archbishop Seán O’Malley, had little choice but to sell the church’s land. Hence, the St. John’s complex’s going to Boston College: first a 43-acre parcel for $99 million in 2004; then a 4-acre sliver for $8 million in 2006; and finally the remaining 18 acres for $65 million in 2007. The institutional rule O’Connell pioneered had eviscerated the institution he built—and, with that last sale, all of his beloved land.

As painful as it was for the faithful, the Catholic Church’s sex abuse scandal was a godsend for Boston College. Before it, BC was landlocked and unable to grow, hemmed in on three sides by wealthy residential neighborhoods and on the fourth by the Chestnut Hill Reservoir. Now, suddenly, the school had more land than it knew what to do with. Well, that’s not exactly true. It did know what to do with it: build, and then build some more.

BC has a lot riding on its new parcel. Nothing less than “the future of Boston College” lies north of Commonwealth Avenue, says one prominent alum, who didn’t want to be seen as speaking for the school administration. The school was so anxious to grasp that future that it offered a significant premium for the archdiocesan plot—nearly $70 million above assessed value, or more than $1 million more per acre. According to a source with knowledge of the deal, BC hurried to complete the 2004 sale agreement, and the archdiocese, desperate to pay off victims of the abuse scandal, was just as eager to close. Both sides knew O’Connell’s remains could potentially be trouble, but they entered into the arrangement anyway, attaching a stipulation to the sales contract saying that the archdiocese, as the former owner of O’Connell’s body, would assist in arranging for its removal from BC’s new land at some unspecified time in the future.

The archdiocese has tried to live up to its end of that agreement, to no avail: Since it no longer owns the land, it has no jurisdiction over its contents or inhabitants, which means it can’t tell O’Connell’s family what to do with his remains. Technically, BC isn’t similarly restrained, but on a practical level, exhuming O’Connell presents its own problems. “BC, the owner, has not informed us, the family, about the reason why they would want him removed,” says O’Connell’s great-nephew, Edward Kirk. “We didn’t see any real reason why he couldn’t stay where he is.” Even if the family did support a bid to take a jackhammer to Uncle Cardinal’s mausoleum, a probate judge would still have to find a compelling reason why BC couldn’t live with the cardinal’s bones up on the hill. BC hasn’t articulated that to anybody yet. The college likes to think much more big-picture.

The competitive nature of modern-day academia mandates that schools grow or die. In a letter announcing his school’s first purchase of archdiocesan property, BC president Father William P. Leahy wrote, “To have an expanded future, you need a place on which to build it.” His local peers certainly share that outlook. Boston University is overhauling its residential, athletics, and recreational buildings, spurred in part by envy over Northeastern’s $15 million fitness complex, the Marino Center. Suffolk University has a proposed million square feet of residential and academic development in its pipeline. And then there’s Harvard’s Allston master plan, which envisions the transformation of an entire neighborhood.

Competitive pressures dictate that Boston College respond in kind. But BC doesn’t want to just keep up: A strategic plan completed in December 2007 reveals the school’s dreams of “becoming the leader in liberal arts education among American universities.” Not a leader. The. Then there’s the rapidly evolving, increasingly interdisciplinary nature of science research, which demands that colleges invest heavily in new facilities to remain in contention for grant money. BC has already upgraded athletically, jumping from the Big East to the Atlantic Coast Conference in 2005, chasing the prestige—and huge television revenues—enjoyed by the nation’s athletic powerhouses. And to vie for athletes with the likes of Florida State, Miami, North Carolina, and Duke, you need new gyms, new dorms, new playing fields.

Not that you would get a sense of these boundless aspirations from BC’s public statements about its real estate dealings. When the college bought its first 43 acres from the archdiocese in 2004, BC officials painted themselves as their neighbors’ allies, saying the purchase would protect that part of Brighton from overdevelopment. Press reports spoke in broad strokes about the school using its new land for green space, parking lots, and back-office administration. Says one person who has dealt with the college for years, “They talked about kids playing Frisbee.”

“Plenty of people had been told by BC since 2004 that the college wouldn’t build dorms on the archdiocesan land,” says Michael Pahre, who lives up the street from the seminary. Two months after that property sale went through, the mayor’s task force on BC expansion sent the school a letter saying the neighborhood would oppose any dorms in Brighton, and for three years BC honored that sentiment. But in early 2007, in a move O’Connell himself surely would have appreciated, college officials suddenly decided to drop 600 undergraduate beds in the middle of the property. The old bait and switch was in play.

“They sprang it on us,” recalls Alex Selvig, a Lake Street resident whose opposition to BC’s expansion prompted an unsuccessful run for city council last year. “It horrified people.” One of those people, in public comments reflecting a broader hysteria, said that if BC followed through on its new construction agenda, “our lives will turn into a living hell.” Others accused the college of being an “insensitive and arrogant” institution, of seeking to “systematically destroy our neighborhood.” Another panned the college administration as “gold-plated idiots.” At an April meeting between the college and Brighton residents, one woman compared BC to “a giant ogre stepping on things.”

The name-calling has gone both ways. BC spokesman Jack Dunn has said some of the school’s Brighton opponents are “ardent obstructionists.” He has also said, “Everyone wants to see college students live on campus, unless they happen to live close to campus.” (Dunn declined to comment for this story, and another BC official did not return phone calls.)

In December, the college filed master planning paperwork with the city of Boston. The documents foretell a $1.6 billion spending spree that goes well beyond creating a place for students to play Frisbee. The 65-acre parcel of former archdiocesan land would see a 76,000-square-foot fine arts facility, three undergraduate dormitories (now totaling only 500 beds, a magnanimous gesture by BC), townhouses for theology graduate students, renovated archdiocesan buildings for academic and office use, a 500-car parking garage, and a 2,000-seat baseball and softball complex attached to a 100,000-square-foot field house. Using the seminary land for dorms and playing fields would then allow BC to build a 285,000-square-foot university center, some smaller undergrad dorms, and a 200,000-square-foot athletic and recreation center across the street, on the main Chestnut Hill campus. That would be 1.9 million square feet under construction—just in the 10 years the official planning document covers.

Because here’s the thing: Boston College still thirsts for more. For the past three years, for example, it has tried to grab away from the state a 4-acre slice of land called Beer Can Hill. And if the school visits untold disaster upon the entire metro area in the process? That’s merely the cost of doing business.

As the name implies, Beer Can Hill is a small mount—specifically, a 32-foot-high heavy rock ledge—that BC students frequently litter with alcoholic detritus. Controlled by the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (MWRA), it’s sandwiched between the Chestnut Hill Reservoir and BC’s lower campus. The hill also sits atop a critical juncture in the subterranean system that pipes drinking water into Boston. According to a source close to the talks between Boston College and the MWRA, the school has said it wants to level the hill and use it for nothing more than soccer fields. A bit cavalier, considering that if Beer Can Hill collapsed, some 2 million people would lose water for days, if not weeks, says one MWRA source.

BC knew that it would face opposition to its plans, so it hired an engineering team that told the MWRA’s engineers, “We could do it safely.” When the agency’s board disagreed, the college brought in some political muscle: Jack Brennan, a lobbyist, former state senator, and close ally of ex–Senate President (and BC alum) William Bulger. Brennan’s 2007 filings with the state show him performing work on BC’s master plan and other unspecified “property issues.” He’s also made campaign donations to the elected officials whose districts abut the college: state Senator Steven Tolman and state Representatives Michael Moran, Kevin Honan, and Frank Smizik. But those efforts notwithstanding, his firm’s lobbying of the MWRA board on BC’s behalf—”It was some heavy stuff,” the MWRA source says—didn’t work. Last November, the board passed a resolution condemning the proposed plans, citing the potentially dire consequences of any damage to the water lines.

Still, no one thinks that setback will really stop BC. Asked whether the college is still interested in buying Beer Can Hill, Moran replies, “I haven’t asked, but I don’t have to ask that question to get an answer. They were interested in it 30 years ago, and they’ll still want it 30 years in the future.”

If BC only understands brute force, which seems to be the case, its Brighton neighbors are lucky to have an ally in William Galvin. Along with living on Lake Street for decades, he is a BC alum, and in general not a man you want mad at you. In a career built on high-stakes conflicts, he’s taken on much bigger game than Boston College (Putnam Investments, Merrill Lynch, and the entire hedge fund sector, to name three—and that’s just in the past five years). And in the case against his alma mater, he doesn’t like what he sees.

In February, Galvin sent a letter of protest to the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA). Taking pains to remind the BRA that he was writing as a concerned resident and not a public official, Galvin blasted BC’s proposed expansion. He condemned the college’s long-standing “encroaching presence” in Brighton, not to mention this particular “dramatic incursion into the existing residential community” for having “the potential to destroy the quality of life of the nontransient residents.” BC’s construction plans, Galvin wrote, would represent “a dramatic change of use” for the land, one that “overwhelms and ultimately destroys the residential neighborhoods.”

While Galvin the private citizen opposes BC’s plans on personal grounds, an office that he oversees, the Massachusetts Historical Commission, could very publicly make the school miserable. If, that is, someone atop the historical commission were so inclined. (Ever shrewd, Galvin declined to comment for this story.)

What the commission has already done is issue a five-page letter decrying BC’s plans and warning that new construction—especially dorms—would ruin the surrounding historic neighborhood, implying, in effect, that BC couldn’t do more harm if it were to torch all of Lake Street. Most notably, however, it raised the cause of one Cardinal O’Connell, whose remains lie uncomfortably close to the planned parking garage’s footprint.

In 1928, a year after moving to the seminary, O’Connell allegedly oversaw the disinterment of at least one Sulpician priest who’d been buried on the grounds. The “allegedly” is key—since if it didn’t actually happen, then there are Sulpician bodies still stuffed into unmarked graves on BC’s new land. Sulpician bodies stuffed into unmarked graves would fall under the historical commission’s purview. And that would make BC’s new buildings harder to build. James O’Toole, O’Connell’s biographer, says there’s “a strong oral tradition among the Boston clergy” that more than one Sulpician was buried on the site, though he’s “virtually certain” that none remain today. The archdiocese doesn’t have history on its side, though: In 2006, construction workers in Roxbury

discovered the corpses of 600 unidentified people on the grounds of a demolished church.

Galvin—or his office’s—interest in these unmarked graves, however legitimate, could do more than wreak havoc on BC’s construction schedule. It could stop it entirely. The college will likely try to tap some form of public funds in its quest to build out the chancery grounds, and if it does, that will give the historical commission a) statutory oversight, and b) standing in court. This means Galvin can reserve the right to sue BC, something no one, in particular his enraged neighbors, has been able to do. Strategically, he’d have good reason to. He and everyone else know BC doesn’t need another drawn-out court battle: A dozen years ago, BC fought with the city of Newton over a student center the school wanted to build. In 2003, BC finally won a favorable ruling from the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, but by then it had abandoned the project. The lesson: You don’t need to beat Boston College. You just need to outlast it.

Boston College was also looking to expand a century ago. The school, then in the South End, was confined to a single city block, and as the surrounding neighborhood gained population, that density cut off any future growth for BC. So, in 1907, with encour

agement and aid from Cardinal O’Connell (an 1881 BC graduate), it packed up and moved to what was then farmland in Chestnut Hill. Today, of course, the school is accused of carrying the same imperial air that brought it west and made O’Connell famous. The difference is that this time BC doesn’t have the cardinal on its side. By conscripting his bones into the fight, Galvin’s historic commission may have at last found the lever that can thwart the school.

O’Connell, we can safely guess, would like that ending. Because while bad for BC, it would also mean that, from his perch high atop that hill, looking down on us all, the cardinal still runs this town.