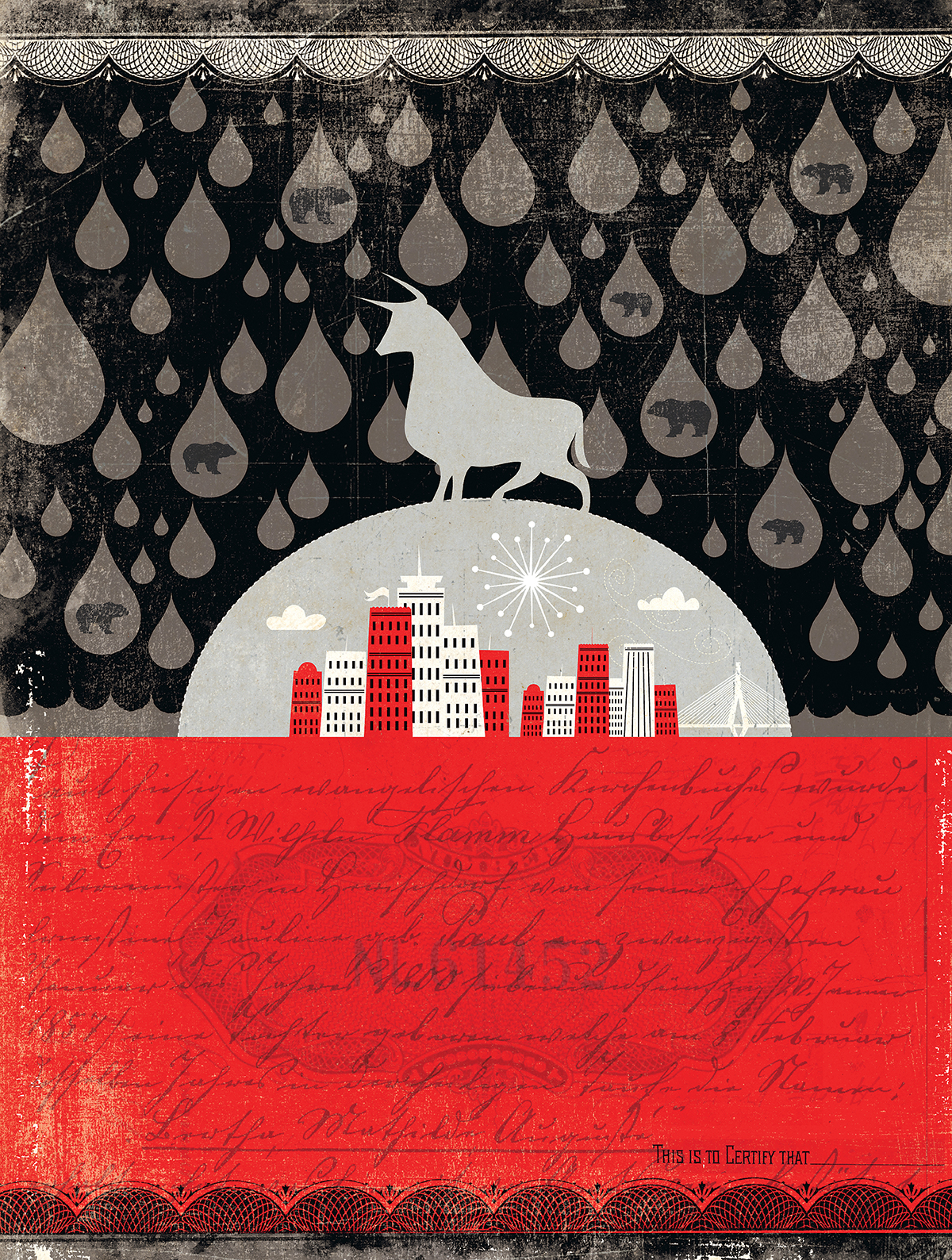

The Once and Future Hub

ILLUSTRATION BY ANDREW BANNECKER

Fidelity fired 1,300 people in November and plans to ax 1,700 more this quarter. Dozens of local car dealerships could go belly-up along with the Big Three. The malls are empty. The “collections” that used to be malls are empty. The state has no money and whatever town you live in has less. Oh, and the last time the U.S. economy hit the skids, back in the early ’90s, Boston recovered with all the speed of an asthmatic banana slug.

But as a wise man once said: Don’t have a cow, man. If history tells us anything, it’s that a recovery will come. And when it does—be it in a month, a year, or a decade—Boston will be out in front. Says Ed Glaeser, Harvard economist and director of the school’s Rappaport Institute for Greater Boston, “I certainly expect our economy to come back, and come roaring back.”

So put on your rose-colored glasses and look past the current hardships. Boston is positioned for an economic dominance unseen since our 19th-century merchant fleet (yes, you have to go back that far) ruled the high seas. Here are 14 big reasons why.

1. Because we’ve learned from our past missteps.

Whereas the local economy used to lean all too heavily on our mutual-fund giants and a few large, vulnerable corporations, it now rests on a diversified group of industries drawing their strength from Boston’s greatest asset, its collective brain power. “Last time, we led the charge down the toilet,” says Wellesley College economist Karl Case, recalling the early-’90s collapses of Digital, Wang, and Bank of New England. Boston’s real estate market imploded, too, and for much of 1991 the area’s unemployment rate ran a full point higher than the national average. “Having lived through it once before, we didn’t get the excesses again,” Case says. While the financial world’s demise cripples New York, costing that city an estimated 225,000 jobs over the next two years, the damage here will be a lot less severe.

2. Because the policies of a new president, sworn in on the 20th of this month, will usher in a new epoch for America—and profits for Boston.

3. Because, for instance, Barack Obama has promised near-universal healthcare.

And since Massachusetts is the only place this side of Canada already providing it, we stand to benefit from such a push. Obama’s proposed National Health Insurance Exchange, which would create a market that allows people who don’t have employer-sponsored health insurance to buy their own, “is very much modeled on the idea of the [Massachusetts Health] Connector,” says Katherine Swartz, Harvard professor of health policy and economics. Studying Massachusetts, she adds, will help the Obama administration determine what the minimum offering of services should be, and who should be eligible for them. “Clearly, they’re going to learn a lot from the types of issues the Connector board had to struggle with.”

4. Because, even more important, a vibrant culture of healthcare entrepreneurship has sprung up here in response to the challenges of universal coverage, and Obama’s agenda could mean big business for those firms.

One such startup is Cambridge-based Sermo, which has developed a networking website that allows doctors to log on anonymously and compare notes on new drugs and treatments. The company makes money by selling access to interested non-physician parties (pharmaceutical concerns, potential investors, etc.), and with 500,000 doctors already members and 10 of the world’s top 12 pharmaceutical companies as paying customers, its future looks bright. Even in these tough times, Sermo officials say they’re hiring away, “actively increasing” their current 90-person staff.

The bosses at American Well are also in hiring mode. The three-year-old Boston firm, which provides patients with M.D. consultations via webcam, has doubled its workforce every year since its inception. As more Americans gain health insurance and appointments for primary-care physicians become consequently even harder to schedule, American Well should do quite well. Not that it’s hurting right now: It recently struck a reimbursement deal with Hawaii’s largest health insurer. Say aloha to 610,000 new customers.

5. Because these startups and others like them are the byproducts of the universities and teaching hospitals that, despite the recent gloomy headlines, remain the engines of our local economy.

Start with the schools. Sure, budgets have been slashed; even MIT and Harvard are looking to cut $50 million and $105 million in annual spending, respectively. But the universities’ principal output—brains—makes for a highly adaptable infrastructure. In places like Michigan and Ohio, after any bailout they’ll still need to literally rebuild their economic landscapes, since too many jobs will be lost for good. By contrast, there will always be demand for top minds and the institutions that school them. “We employ close to 100,000 people, and we aren’t going to relocate out of state,” notes Richard Doherty, president of the Association of Independent Colleges and Universities in Massachusetts. All told, the universities pad out the state’s bottom line to the tune of $27 billion. Yes, Harvard has lost $8 billion this fiscal year from its endowment, but it’s still got $29 billion in the kitty. You can’t say that for Lehman Brothers.

Similarly, our medical complexes remain fundamentally strong. Brigham and Women’s and Mass General are perennial top-10 finishers in U.S. News and World Report‘s hospital rankings. Taken together, the city’s teaching hospitals and affiliated med schools provide 110,000 jobs and $24 billion a year for our local economy. Like the universities, they aren’t going anywhere. Actually, they’re getting bigger: Despite everything, Mass General is still on track to spend $686 million on the state’s most expensive hospital expansion, set to open in 2011.