The Once and Future Hub

ILLUSTRATION BY ANDREW BANNECKER

6. Because much of what goes on in that new building will doubtless be aided by the National Institutes of Health, which for 14 straight years has sent more cash to Boston than to any other city.

Massachusetts’ total haul has habitually led that of all states, save California (though per capita we get roughly four times more). Between 2005 and 2007, the NIH plowed over $6.7 billion into the commonwealth, more than five times what the average state received, and more than one-tenth of all the money doled out nationwide.

Sure, there’s concern that NIH dollars will disappear as the economy worsens. But that didn’t happen during the last downturn, in 2000—funding increased that year and in the years following, and that with a conservative president in the White House. Even more auspicious: As a candidate, Obama pledged to double the agency’s funding over the next 10 years. Anything he does to even come close to that goal will help not only Boston’s medical industry (which includes the top five NIH-funded hospitals), but also our universities. Last year MIT alone received just under $200 million in NIH money, which was more than 26 entire states reeled in.

There’s another local sector fortified by the NIH’s pipeline. Some 450 biotechs are located in Massachusetts, and last year 69 of them received a total of almost $86 billion from the NIH. That free money helped account for $5 billion of the industry’s payroll. For scientists and medical innovators interested in working at top-flight universities and hospitals while having the opportunity to spin their research into startups, the proven flow of NIH backing to local institutions makes Boston exceptionally attractive.

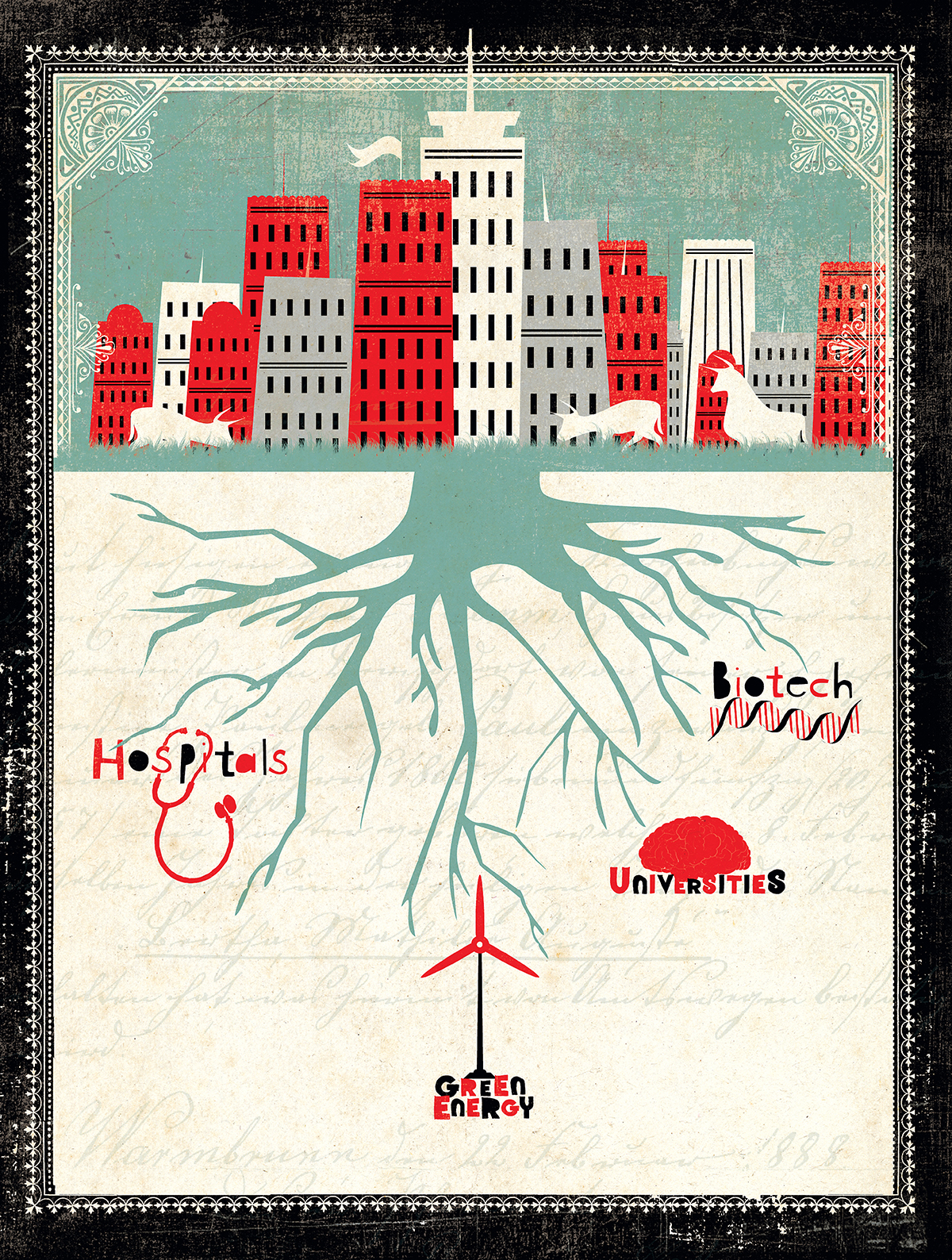

7. Because the links among our universities, hospitals, and the aforementioned startups have created what’s often referred to as a “biotech ecosystem.”

It works more or less like this: You start with an idea, incubated and nourished in one of the universities or hospitals. Angel investors provide seed money to get the venture off the ground. For the ensuing rounds of fundraising, other area venture capitalists pitch in, offering not just cash but coaching that’s informed by a deep understanding of both early-stage development and the local terrain. As the fledgling biotech staffs up, it can turn back to the universities for talent to fill the jobs it’s creating. As it needs business services, it can look to the many technology-support companies to help with everything from animal experiments to producing the proteins needed for lab work. The hospitals right next door can be accessed for human trials. Finally, while it takes its products to market, the biotech can tap the city’s large pool of lawyers who specialize in licensing and commercial deals for new drugs. All the organizations within the ecosystem interact with and need one another, which means one can’t just be yanked from this habitat and expected to perform as well.

Jeff Elton, a senior VP in Novartis’s Cambridge office, notes that the ecosystem has spawned a flurry of new medical drugs, as well as a few successful companies you may have heard of: Genzyme, which enjoyed a $480 million profit last year, is one; Biogen Idec, which boasted a $638 million margin, is another. That performance “is something that a lot of regions just can’t replicate,” Elton says.

8. Because the people who inhabit this ecosystem aren’t panicking.

Oh really, you say. Didn’t the investment bank Rodman & Renshaw just publish a report warning that 113 biotechs nationwide (a fair share of them in Boston, to be sure) have less than a year’s cash on hand and are in danger of going under? Yes, that’s a serious concern (and my, how well read you are!). There’s no doubt that some area biotechs will fold if the economy stays this scary. So many local jobs have already been cut that the tech website Xconomy keeps a deathwatch tally.

But none of this seemed to greatly trouble the businesspeople and biotechies at a recent MIT cocktail reception for alumni entrepreneurs. The function was held at the Stata Center, on a day when the Dow plunged 400 points. As the assembled entrepreneurs sipped wine, snacked on bacon-wrapped scallops, and made the networking rounds, no one threatened to jump out of the building’s famous herky-jerky windows. They all knew Boston’s hold on biotech is safe. Says Elton, who was among the minglers, “Here we have enough activity going on that even if one venture fails, the talent stays. We preserve not just our intellectual assets but our human assets, too, and that’s important as you’re going through a recession.”

9. Because retrenchment could help shore up Boston’s standing as one of the world’s top biotech centers.

According to Christoph Westphal, CEO of Sirtris (his fourth biotech), the loss of VC funds will “probably be more of a problem for the secondary biotech centers, like Raleigh-Durham, Atlanta…six months ago every little place was saying, ‘We want to be a biotech hub.’ I think there’s probably [going to be] this concentration of more and more money in Boston.”

Highland Capital partner Bob Davis adds, “When you find a challenging time and you hunker down, you hunker down in familiar territory where you know where all the tunnels and foxholes are.”

10. Because its ecosystem makes biotech different from the leading local industries preceding it.

Until recently, biotechs used initial public offerings to fund their midstage research. (It can be 10 to 15 years before a biotech startup thinks about profits.) But with that option shut off by volatile markets, companies at that stage of development have increasingly been forced to rely on big pharmaceutical companies like GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer to come in with the money they need.

National behemoths buying out our local flagships may make Bostonians fidgety. After all, Manulife turned John Hancock into a Canadian, Gillette’s run by a bunch of gomers in Ohio, and the thing that used to be Shawmut/BayBank/Bank of Boston/BankBoston/Fleet Boston now sits deep in the vast belly of Bank of America in North Carolina. But Westphal, whose firm was acquired by Glaxo last spring for $720 million, says the life sciences are a whole other animal. His new parent company threw him a three-year, $200 million budget and has since more or less left him alone. “What’s really interesting is what these big [pharmaceutical] companies want…is literally, expressly, an access to this ecosystem,” he says.

A final example, for fans of symbolism: On December 3, the same day the news broke that the venerable company State Street would slash up to 1,800 jobs, a South Korean life-sciences firm called Oscotec announced the opening of a new Cambridge office. Like everyone else in biotech, the South Koreans saw what was going on here, and wanted in.