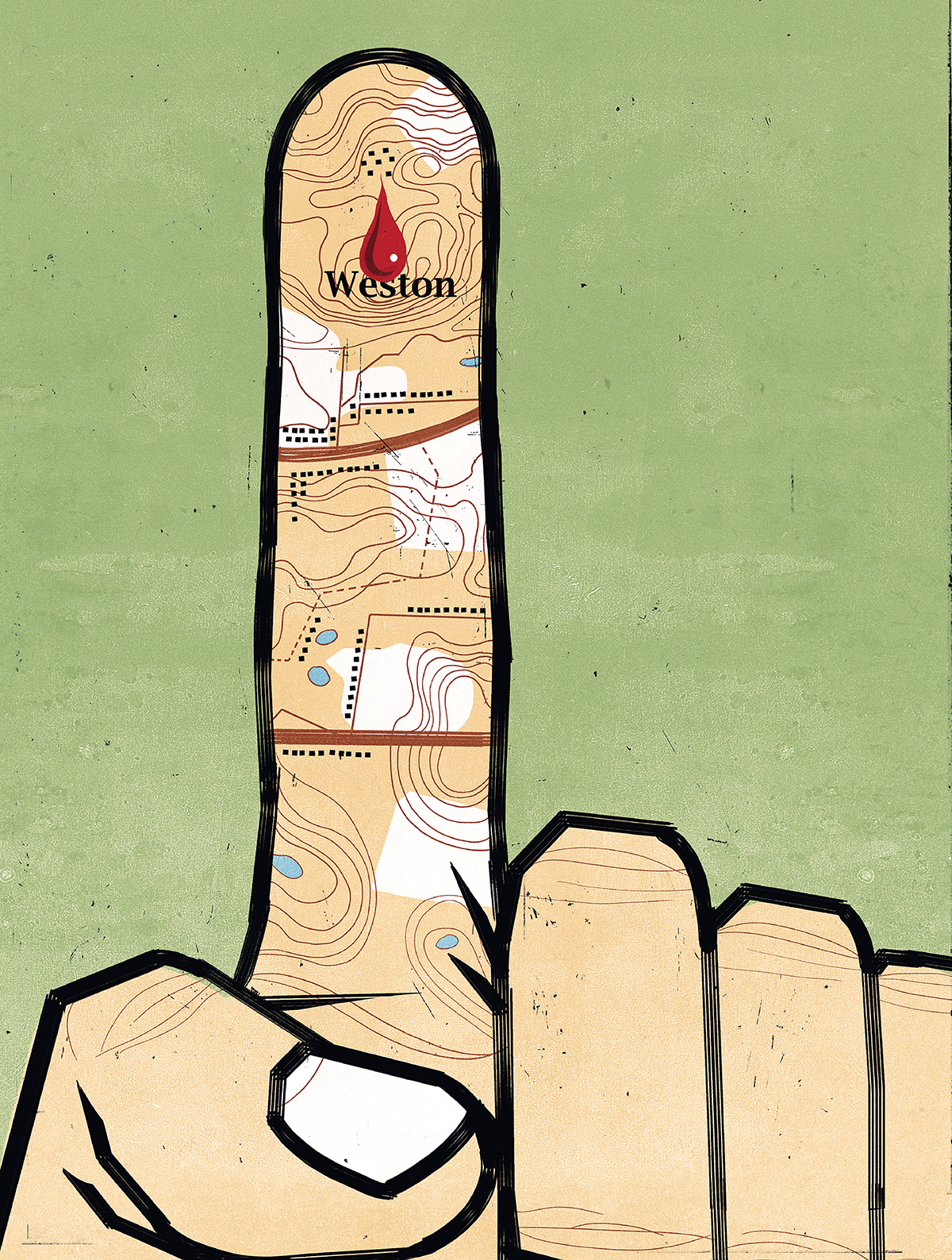

A Diabetes Outbreak in Boston’s Suburbs

Illustration by Shout

The call comes at 3 a.m. Shannon Allen rolls over in her bed at the Four Seasons in Los Angeles and grabs her cell phone. “Ray,” a sleepy Shannon says, “it’s 3 in the morning.” She knows the game tomorrow will be perhaps the biggest of his life. He’s the most focused, disciplined man she’s ever met: He should be sleeping.

“I’m praying,” Ray Allen says, calling from the team’s hotel, the Beverly Wilshire.

“Ray, you’re ready. You’ve worked your whole life for this moment. You’re prepared….”

“No,” Ray cuts her off. “I’m praying for Walker. He just doesn’t seem right.”

Walker, their 17-month-old son, hadn’t been his usual wild-man self since they touched down in Los Angeles five days ago, on June 9. On June 10, Ray and the Celtics lost to the Los Angeles Lakers in Game 3 of the NBA Finals, giving L.A. their first win in the series. On the bus ride back to the hotel, Walker vomited all over Shannon’s No. 20 jersey. He spent the next few days lolling about, listless and lethargic, wanting only to eat and sleep. Juice, Momma, he said over and over. He had never asked his momma for juice before; Shannon thought he must be dehydrated, maybe jet-lagged. But nearly a full week later, Walker wasn’t feeling any better, and Ray, on his visit to the hotel earlier that evening, had been concerned. So concerned that he couldn’t sleep. So concerned that he prayed. So concerned that he calls Shannon now and wakes her up. “Please keep a close eye on him,” he says before hanging up. “I’m worried.”

Walker sleeps through the conversation in the bed next to Shannon. Soon she herself drifts off. But at dawn, Shannon wakes to Walker throwing up all over the sheets. She phones the hotel’s on-call pediatrician. Take him to Cedars-Sinai and have them run blood work, the doctor tells her. Just to be safe.

The hospital’s pediatric physician does not think drawing blood is necessary. Walker probably has a little bug, she says. But Shannon insists. Twenty minutes after leaving the room with the vial, the doctor returns, tears in her eyes, her face wan. She tells Shannon that her son has type 1 diabetes. A normal blood sugar count is between 80 and 120; his is 639. Walker’s pancreas is not functioning. His blood is full of ketones—the acid residue that develops when a body burns fat instead of sugar in a desperate bid for energy. If Walker doesn’t get insulin soon, he will die.

Shannon calls Ray. He’s in a cab on the way to the Staples Center for Game 5—the final game, if Boston wins. He wonders whether he should forget about basketball tonight. “Tell me what to do,” he begs Shannon. She tells him to play the game. But that night Ray’s mind is elsewhere. He scores 16 points on 4-of-13 shooting, and the Celtics lose. He leaves the arena immediately afterward.

Coach Doc Rivers issues a vague statement to the media about Allen attending to a sick child. When the team boards a Boston-bound plane Monday morning to prepare for Game 6 on Tuesday night, Allen stays behind. It doesn’t take long for rumors to circulate through the blogosphere and the sports bars of Boston: Allen might miss the contest. He spends all of Monday at Cedars-Sinai with his wife and son.

Walker is by this point in stable condition. But the Allens listen to doctors and nurses and nutritionists explain how the boy’s life—and theirs—will never be the same. Walker will need daily shots of insulin. Mealtimes will become an exercise in vigilance.

Ray and Shannon hire a private nurse, who flies with the Allens overnight on the Celtics’ plane back to Boston. Further tests are scheduled at Children’s Hospital. But first, Ray Allen must play Game 6. That night, as part of his pregame ritual, he palms the parquet floor before trotting onto the court. He points to his family sitting courtside: Shannon and Walker, now joined by oldest son Walter Ray Allen III and daughter Tierra.

Allen scores 26 points, and the Celtics bring home their 17th NBA title, their first in 22 years. Allen’s family rushes the court. Confetti rains down and Ray reaches for Walker, hoisting the little boy in his arms.

Two days later, when Allen announces to the press that his son has diabetes but is doing well, newspapers and TV stations run a photo from that championship night—of Allen holding Walker and raising his thumb in triumph. It seems to tell the whole story.

But it doesn’t. Ann Marie Kreft, a mother in Weston, sees the Walker Allen piece on the news. A few weeks later she finds out the Allens live just over the town line, in Wellesley. For Kreft, Walker Allen has just added to the mystery she is desperately trying to solve.

Celtics star Ray Allen and his son, Walker, one of seven MetroWest children recently diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in a two-mile radius. (Photograph by Tim Llewellyn)

No one knows for sure what causes type 1 diabetes. It is partly genetic (sufferers have predispositions to autoimmune diseases in general), but the condition itself is also triggered by one or more environmental agents. After Ann Marie Kreft’s son, Gus, age seven, was diagnosed a year and a half ago, she dedicated herself to finding out why, exactly, her son developed the disease—and why, exactly, so many other kids living nearby had it, too. The state does not keep a registry of diabetic children, so Kreft, with the help of other concerned parents, started compiling her own. What she found is that something unsettling is going on in the suburbs of Boston. And though it has taken a while, she is no longer the only one who sees trouble in the data she’s collected.

In the medical community, there’s a general sense that diabetes diagnoses are increasing everywhere, with the Centers for Disease Control estimating that one out of every 4,166 children under the age of 20 can now expect to develop the disease. What’s happening in Massachusetts is alarming, but for a slightly different reason: Children are being diagnosed within weeks or months of one another, some of them living within a close geographic range. According to Kreft’s figures, seven have been diagnosed within a two-mile radius encompassing Weston and Wellesley. There have been five new diagnoses in just 10 months in Concord. Five children have been diagnosed on one 30-house street in Plymouth. A Boston University journalism professor, Elizabeth Mehren, recently e-mailed Kreft about her son, who was diagnosed within six months of another kid from the same Hingham street; a third child on the street had also been diagnosed around that same time, as had one on the street perpendicular. Suburban moms from Walpole to Marshfield, Westford to Belmont, tell Kreft that they are worried about their child, their neighborhood, their town.