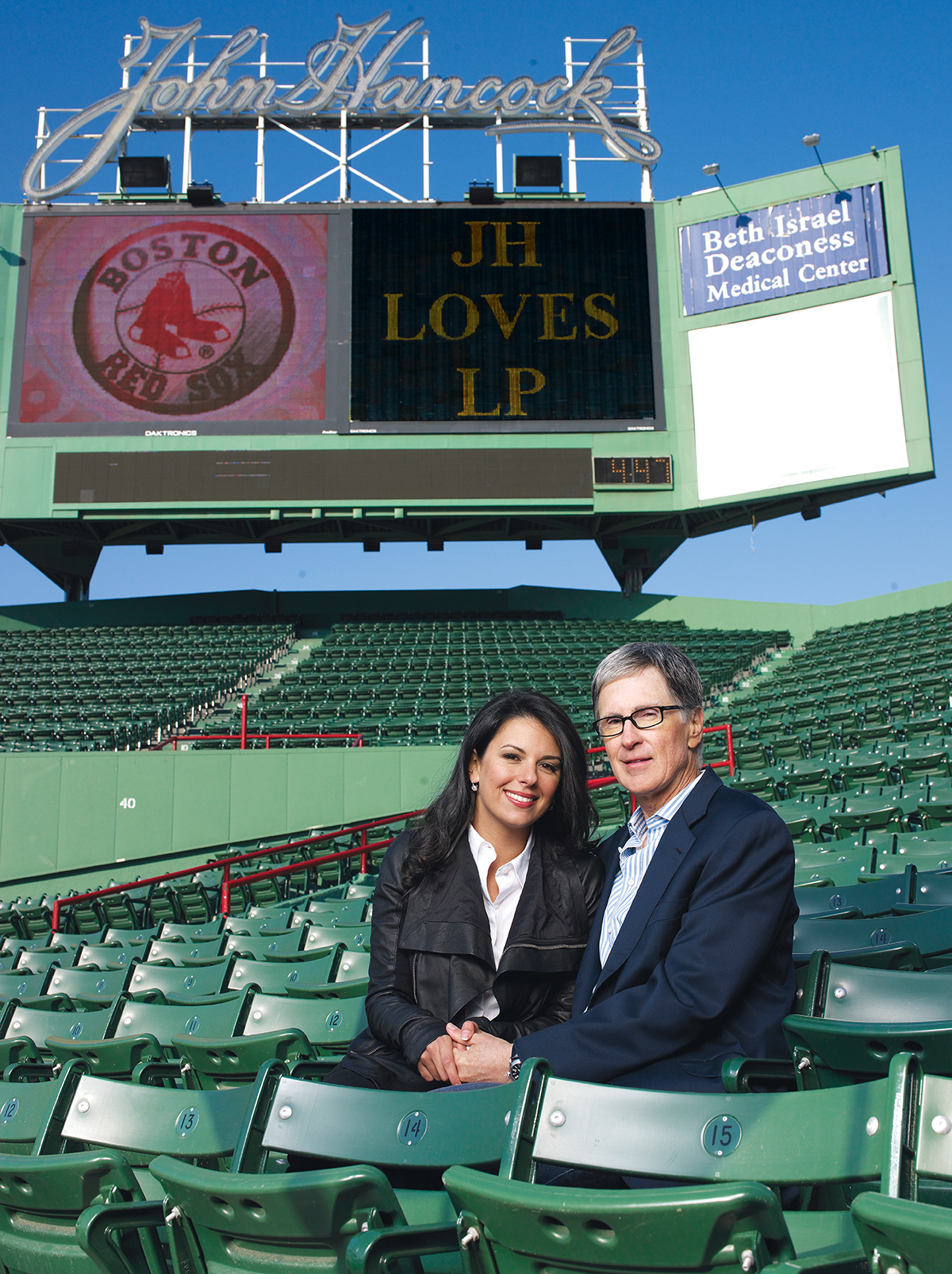

The Owner Takes a Wife

Pizzuti always wanted an outdoor wedding reception under a big white tent. Henry, it just so happens, has access to a suitable venue. (Photograph by David Yellen)

Pizzuti soon left for Europe, and Henry went on with his life. A week after he and Werner watched the Celtics’ championship win over the Lakers from his courtside seats, they hosted a victory bash at Fenway. During the festivities, it began to rain.

That night, Henry e-mailed Pizzuti.

Dear Linda,

A man needs a muse. Well, he doesn’t really. He doesn’t need nearly as much as he generally thinks he does. A man is greedy. Greedy for what he doesn’t think he has and what he thinks he wants.

We probably wouldn’t have wandered far beyond the basic necessities without that pushing us. Progress is one of its most important byproducts.

So you will ask, “Why are you writing this?” Because a brief encounter-and-a-half with you gave a cool spin to this little blue planet from my vantage point.

We feted the Celtics tonight and the skies opened. The sun emerged and created a giant rainbow between the city and the park. We were transfixed.

You only saw it if you were in the right place. I was in the right place when I noticed you.I barely know you. I don’t have any illusions about capturing your heart. But the world is brighter, better, lighter and warmer when a man imbues a woman he knows—even tabula rasa—with the attributes I believe reside in you. It’s the small things that ultimately matter. The subtle things.

I am honest. I don’t play games. And I see no reason not to say that I’ve been smitten by you and you’ve done me a great service.

You’ve very innocently made my world brighter, better, lighter and warmer.

So thanks.

No response is necessary because a man doesn’t need nearly as much as he thinks he does.

But Henry waited for her response anyway. When it finally came, it wasn’t quite what he’d hoped for.

A man may not need as much as he thinks he does, but courage and honesty should be acknowledged. I am not so naive as to believe I actually possess the qualities you attribute to me. But thank you.

After earning her master’s at age 26, Pizzuti—determined to avoid the procession into marriage, suburbia, and children—broke up with her then-fiancé and moved to the North End. Living alone and loving it, she was up early every morning to hit the gym or a dance studio for salsa lessons; after long workdays she juggled a full calendar of charity and social commitments. Trying to keep track of her could be exhausting.

In Prague, partway through her trip to Europe, Pizzuti found herself thinking about Henry. He had followed up after her e-mail with, “Just struck me—the similarities to Cyrano. Except the young Adonis is a BlackBerry”; she joked back that thankfully he didn’t have Cyrano’s legendarily big nose. She liked the highbrow banter, and she liked Henry’s willingness to bare his soul. By the time she landed in Boston, she had convinced herself it would be okay to be friends.

But nothing more: When Henry suggested they go on a date, she wrote back, “It would be a fantastically bad idea to go out with you. It would lead to trouble and gossip in a small town.” Turning to self-deprecation, he responded with a list of additional reasons she should refuse, including “My expiration date was about 10 years ago.” Won over, Pizzuti agreed to meet him the following week at the Golden Goose market in the North End, where they would buy supplies for a cooking lesson on his yacht.

Three days before their “friend date,” as Pizzuti dubbed it, Henry met Kane at the 1369 Coffee House in Central Square. (Henry, who’d only recently started drinking coffee, had become an effusive fan of the place—even flying one of its managers to his house in Boca Raton to train his staff on brewing techniques.) Afterward, Henry drove to the North End for dinner with Werner and his daughter, Amanda. He got lost and called Pizzuti for directions. She guided him in, but he was so late that the Werners had left. So he called again: “I’m across the street at Florentine. Come down!” Pizzuti refused, telling him she’d see him in three days as they’d planned, yet 45 minutes later she appeared at the restaurant. They strolled the neighborhood for hours, and at one point Henry tried to take her hand. She had to explain to him that it was too intimate for friends.

When Henry and Pizzuti met the cooking instructor at the Golden Goose, she realized it had been years since Henry had been to a grocery store, and probably decades since he’d cooked. But he seemed thrilled to go along with whatever she wanted to do. On the boat, Henry presented her with custom aprons: for her, “Ms. Pizzazz” (his nickname for her), and for himself, “Fantastically Bad Idea.”

The next night, July 10, they attended Sox pitcher Josh Beckett’s Beckett Bowl fundraiser, making a concerted effort not to be seen together. They followed up with a walk around the Bunker Hill Monument—this time, they held hands—and a late dinner at the Franklin Café, where a waiter told Henry’s manager (Pizzuti was still insisting on a chaperone) that the couple looked madly in love.

A week later, Werner convinced Pizzuti to travel to L.A. to rendezvous with the Circus, who would all be in town while the Sox played the Angels. Werner’s house there sits on a golf course with views of the rolling fairways, which inspired Henry to buy a tent and—mindful of the rules of this evolving “friends that hold hands” relationship—eight sleeping bags for a backyard campout. “John thought it would be romantic,” Werner says. “I told him that was all well and good, but I preferred to sleep in my bed. I offered to make them breakfast in the house the next morning.”

That night, in what Pizzuti regards as quintessential Henry, he had a debate with himself, out loud, about whether he was in love. He concluded that the answer was probably no. She thought, Okay, great, thanks, did I ask if you were? But the next evening, after screening Mamma Mia! at the home of a producer friend of Werner’s, Henry changed his mind. “I must be in love,” he announced, “because there’s no way I would have sat through that movie if Ms. Pizzazz hadn’t been next to me!”

For her part, Pizzuti was learning to take his directness in stride. “If he’s thinking something, he shares it,” she says. “I thought he was a bit nuts. Mostly I just laughed at his declarations.”