The Scapegoats

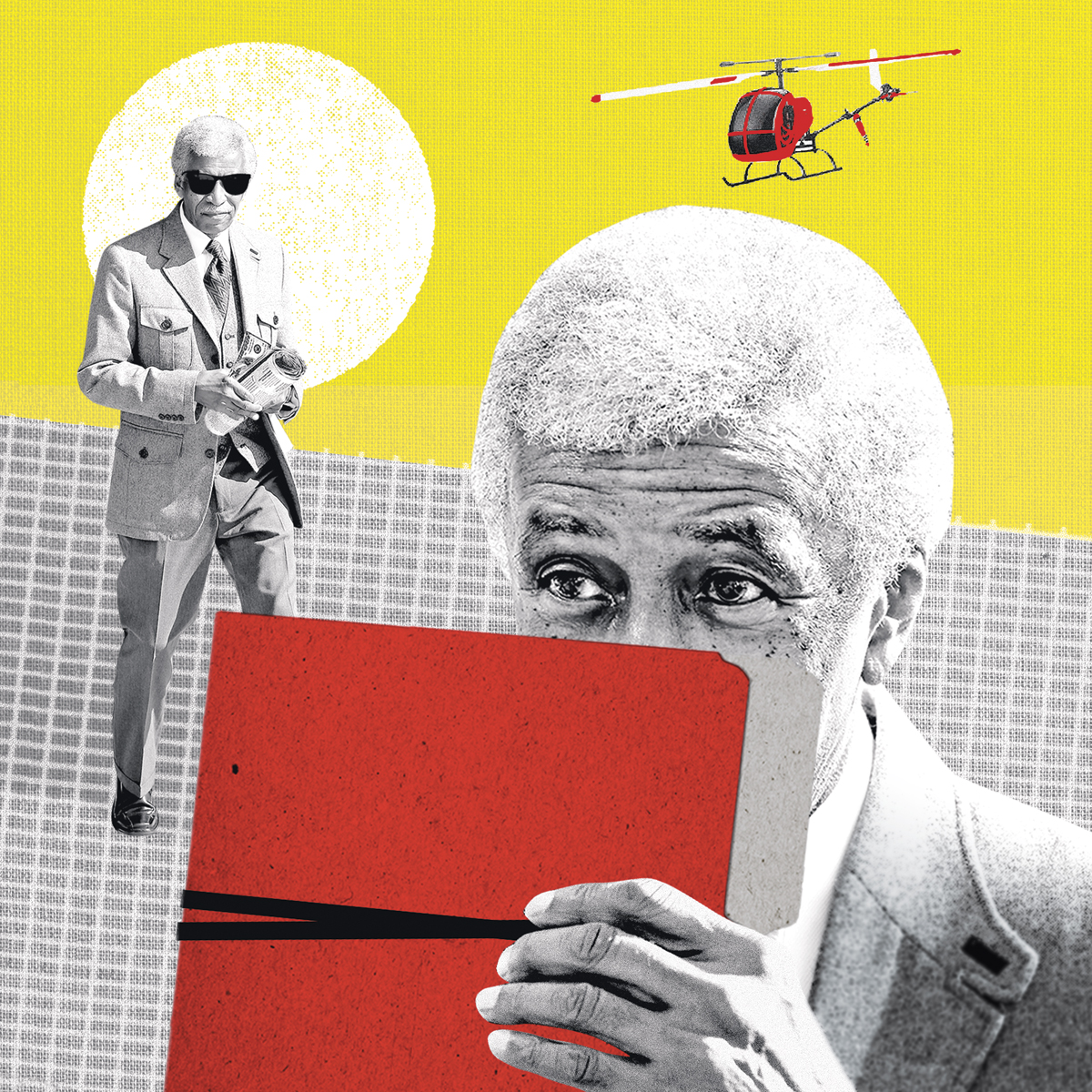

FBI informant Ron Wilburn, lead witness in the cases against Dianne Wilkerson and Chuck Turner. / Illustration by Wes Duvall

THOUGH I DIDN’T SEE HIM at the time, the press photos showed a man dressed for court as he always dresses: in beautiful, ruling-class suits, carrying himself with patrician dignity. Ron Wilburn, even at 71, had a full head of hair, which he cropped close and kept a respectable gray. The hair matched the thin mustache, and the whole coiffed presentation set itself against Wilburn’s rich mocha skin. In that dour federal courtroom, this aging man, a business consultant turned FBI informant, looked not unlike Nelson Mandela.

Wilburn had already brought down powerful people. Months earlier, the conversations he’d recorded had led to state Senator Dianne Wilkerson pleading guilty to eight counts of attempted extortion. And now, on a late-autumn day inside the John Joseph Moakley courthouse, he was testifying about corruption again, speaking against Boston’s incestuous and rigged political system — and how he’d bribed City Councilor Chuck Turner with $1,000 to help him get a liquor license from the city.

Wilburn’s testimony would make headlines. Not only because he revealed that the FBI had paid him for the conversations he’d recorded with Wilkerson and Turner, but also because of how much animosity he held for the FBI handlers Wilburn felt had knowingly pierced the anonymity protecting him, and then discarded him when he was most vulnerable. Wilburn said on the stand that without him, there would not have been a case.

Wilburn made a curious witness, always answering more than the question asked of him, giving contentious, rambling responses: At one point, he shouted at the U.S. attorney, who was putatively on his side. When his time was done, Wilburn left the stand, angry. Was there something more he wanted to say?

Two nights after he’d testified, I went to Wilburn’s home. He lives in a large apartment complex outside the city. I waited at the door, and waited, and was about to ring again when Wilburn appeared. He wore a T-shirt. He looked at me with suspicion.

I told him I thought there was a lot he’d left unsaid: about his experience, about a broken political system, about a culture of corruption and to what extent it had taken over Beacon Hill and City Hall. It seemed that from where Ron Wilburn stood, that sort of corruption didn’t begin — or end — with two politicians from minority neighborhoods.

“No, no,” he said with a laugh.

Last month, Dianne Wilkerson was sentenced for accepting more than $23,000 in bribes. This month, Chuck Turner will be sentenced for taking a $1,000 bribe. And by next month, we’ll likely forget about the whole thing. Yet the Turner and Wilkerson cases shined a light on a part of the city notable for its brutally political cover-my-ass-first-and-screw-you-second trysts. But for all the questions those cases answered, there was so much that remained concealed. Convicting two politicians may provide a sense of civic satisfaction, that bad deeds inevitably result in punishment. But as a review of court transcripts, case documents, and numerous interviews makes clear, it did nothing to address the larger issues Ron Wilburn first brought to the FBI.

BEFORE THE TURNER TRIAL, Wilburn talked a lot about how cooperating with the FBI was a public duty, a means to better the community. He saw himself as a black man of some standing. Over the years, he had owned his own consulting business, been a principal at WHDH, and trained managers for Omni Hotels.

In the early 1990s he befriended a young Dominican man named Manny Soto. Wilburn liked Soto not only because Soto had entrepreneurial drive, but also because Soto allowed him to carry out his duty as a self-styled civil rights leader. “In these times, in this city, when it feels like we’re moving backward as far as affirmative action and everything else,” he told the Boston Globe in 1996, “I think it’s the responsibility of established African-Americans like myself to nurture talent….”

As time passed, Wilburn helped Soto get a line of credit, open a used-car lot in Jamaica Plain, and deal with the licensing and paperwork associated with starting a business. The two remained close, and in 2000 they opened a nightclub together: Mirage at Estelle’s. Soto was listed as the manager, and Wilburn appeared as a low-ranking director. Wilburn preferred this diminished role. “Ron connects people. That’s what he does,” says James Dilday, a liquor-license lawyer who once represented Wilburn. “He’s a behind-the-scenes guy.”

But neither Soto nor Wilburn seemed to have any idea what they were doing running a club. “They mismanaged their fucking money,” says someone close to the men. Some vendors were paid infrequently, and when they were, it was often in cash, this associate says. Wilburn at one point tried raising the club’s profile by saying Red Sox pitcher Pedro Martinez would soon invest $400,000 to become a co-owner, says another person with knowledge of the situation. Martinez never got involved.

But Dianne Wilkerson did. Wilburn approached the state senator from Roxbury in 2004, just before the Democratic National Convention came to Boston, asking for a favor. He thought the convention could bring in a lot of money for the club. Problem was, the electric company had shut off Mirage’s lights. Soto hadn’t paid the bill in four or five months, Wilburn would later testify, and the club owed between $12,000 and $19,000 in back payments. So Wilburn reached a deal with Wilkerson: For a few hundred dollars, he testified, she would talk to NSTAR and get the electricity back on.

In the end, though, Mirage’s money woes were the least of its problems. There were stabbings, drug use, sex in public. A staff member once beat up a customer. The community around the club came to despise it. By 2005, after endless 911 calls and visits by the cops, the Boston Licensing Board had had enough. It placed Mirage at Estelle’s on six months’ probation. In February 2006 the club filed for bankruptcy. In 2007 Soto pleaded guilty to dealing cocaine.

Despite all the problems with Mirage, however, Wilburn wanted to expand his empire. In 2004, a year before Mirage’s probation, he went to Wilkerson and — as he later testified — bribed her with at least $1,000 to help him open another nightclub. By early 2007, that plan had come together. He had a new business partner, and a name for the club: Dejavu. He then went before the Boston Licensing Board, which grants liquor licenses in the city.

IN MASSACHUSETTS, STATE LAW mandates the number of liquor licenses a city or town may issue. In most places, that number is tied to population. But not in Boston. This quirk in the law owes itself to the election of Mayor John “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald in 1906. It bothered the Yankee establishment that an Irish guy had been chosen to lead Boston. Surely the city would descend into drunken orgiastic excess. So the state decided to cap the number of liquor licenses that could be granted in the city. A century later, that cap still exists. Today there are 1,031 liquor licenses in Boston.

This limited supply creates a pentup demand, which results in licenses selling for a great deal — in some neighborhoods, north of $350,000. To get one, a restaurateur needs not only money but also connections: Businesses must be approved by the local neighborhood association and local elected officials.

The role these officials play in granting a liquor license cannot be overstated. In most cities, it’s a mere commercial transaction. But here, entire state committees and boards are given to the handling of liquor and its licenses — which practically invites corruption. After Wilburn approached Wilkerson, for instance, she ultimately helped draft a law granting more liquor licenses in the city of Boston.

But there are also the subtler, more insidious conflicts. Consider outgoing state Treasurer Timothy Cahill. Among his duties is heading the state’s Alcoholic Beverages Control Commission, which regulates restaurants and bars and issues the actual liquor licenses after local boards have granted them. So it’s a little concerning that the successful law firm in Boston that handles liquor licenses on behalf of restaurateurs — McDermott, Quilty & Miller — held fundraisers for Cahill that were attended by representatives from the very restaurants and bars that Cahill was tasked with regulating. All of this, the grubby give and take of the political process, is perfectly legal, of course. And David Kibbe, a spokesman for the treasurer’s office, likes to remind us all of that. He argues that political donations don’t influence Cahill’s decisions, because “the treasurer appoints three commissioners to hear the [ABCC’s] cases and is not involved [with the process].”

Cahill is hardly the only one with a potential conflict. Boston city councilors are supposed to recommend restaurants, bars, and nightclubs for their neighborhoods. Since 2008 McDermott, Quilty & Miller has donated money to at least eight of the thirteen Boston city councilors. And since 2001 Stephen Miller, a partner in the firm, has given more than $50,000 to local politicians. The relationship between the firm and the council members is so cozy that the head of fundraising for outgoing City Council President Mike Ross is a McDermott, Quilty & Miller lawyer named Joe Hanley. By e-mail, Ross says his relationship with Hanley is friendly and that Hanley “has been the chairman of my campaign for several years, which I notified the City Clerk of as required by law. It has always been my policy to evaluate any licensing requests on their merits, not by the law firm which represents them. I have supported some, and opposed others, of the requests the firm has propounded.”

State law limits political donations to $200 a year for a lobbyist and $500 for a citizen. Larry DiCara, a former Boston City Council member and a longtime liquor-license lawyer, says, “Anybody who thinks some $500 check will get you anything doesn’t understand politics.” Maybe. But keep in mind that what got Chuck Turner in trouble with the feds was accepting a bribe of just $1,000.

IF NOTHING ELSE, Ron Wilburn sure understood the role of politics in getting liquor licenses. And yet it was only when he first presented his floor plan for Dejavu in January 2007 that he appreciated the true influence of the Boston Licensing Board. That three-member body ultimately decides who gets a liquor license in town. And because restaurants make their money off of booze, the BLB also decides, in theory if not in practice, which restaurant opens where, which in turn establishes the makeup of a neighborhood.

When he went before the BLB, Wilburn listened as the BLB board members and their normally acerbic chairman, Dan Pokaski, spoke jovially with lawyers from McDermott, Quilty & Miller. But when it was Wilburn’s turn, there was a shift in tone. Wilburn would later say that he felt the board was racist — merry with the white lawyers but chastising the black entrepreneur. And it is worth noting that of the 20 new liquor licenses granted weeks before Wilburn’s hearings with the BLB, none of them ultimately went to establishments in minority neighborhoods.

But a recording of those hearings offers a different take. Yes, Dan Pokaski was terse in his conversations with Wilburn, but he also told Wilburn he wanted to see a place in that Roxbury neighborhood succeed. The problem was Wilburn’s floor plan, which seemed to outline a nightclub — fewer tables, more open space — and not the “supper club” he had proposed. At the end of one hearing Pokaski said, “We love development of this area…. [But] it’s going to be my recommendation to the board that we postpone this until we get a further clarification of the business plan and a more detailed picture of what the floor plan is going to be.”

Today even James Dilday, the lawyer who assisted Wilburn with Dejavu, says racism wasn’t a factor in the BLB hearings. “That’s a fair assessment,” he told me.

WILBURN’S DISAPPOINTMENT with the liquor board seemed to spur him into action. In February 2007, one month after his first hearing before the board, he began meeting with the FBI. By May 2007, according to subsequent testimony from the bureau’s agents, Wilburn had signed an agreement to be a cooperating witness, to rat out Dianne Wilkerson and whoever else might be corrupt. The agreement paid Wilburn, in total, $29,099.

Wilburn portrays his cooperation as the last and most significant act of his civic-minded career. But he also needed the money. His Social Security benefits and an annuity he had barely covered basic expenses. And his new nightclub, Dejavu, couldn’t get off the ground. So Wilburn seems to have used what he had — information on Wilkerson, whom he claims had already taken three bribes from him — to wrangle what eventually became a $3,000-a-month stipend out of the FBI, which would keep him going until he could find his next gig.

In 2007 Wilburn recorded Wilkerson taking five bribes from him, ranging from $500 to $3,000, in exchange for her help with a liquor license for his proposed club. Among Wilburn’s damning evidence was the now infamous photo of Wilkerson stuffing cash into her bra just steps from the State House.

Wilburn didn’t seek out Chuck Turner until Wilkerson suggested it to him at some point in July. Turner was an activist who relished representing Boston’s poorest neighborhood. He didn’t have the political juice to deliver a liquor license, but if the issue were framed properly, Turner could raise a stink, start a protest. And that’s how Wilburn approached him: Why couldn’t he, a black businessman, get a liquor license? Why was it that none of the previous year’s 20 liquor licenses went to establishments south of Massachusetts Avenue? In his first meeting with Turner, Wilburn intimated that Wilkerson thought it might be helpful for Turner to set up a City Council hearing to examine the issue. Turner said he’d look into it.

On August 3 Wilburn got a call from Turner at home. Turner said he’d like to meet Wilburn in his district office. Wilburn took that to mean that he might be open to a bribe. So he called the FBI, which gave him $1,000 in cash and two recorders. Then Wilburn headed out to Turner’s district office in Roxbury.

If Turner knew the bribe was coming, he certainly didn’t give Wilburn any preferential treatment. When Wilburn got to the office, he had to wait. The woman in front of him talked about “educational issues,” he would later testify. A man waiting in line behind Wilburn wanted to build shrines to kids who had been killed in Roxbury. In all, Wilburn waited for nearly 40 minutes.

When Wilburn’s turn came, he took a seat opposite Turner and talked about how grateful he was for Turner’s support. Moments later, with money buried in his palm, Wilburn reached for Turner’s hand, shook it, passed along the money, and said Turner should take his wife out for a nice dinner. Wilburn said there was more gratitude where that came from.

What’s revealing — when it comes to how business really gets done in this town — is that the bribe to Turner wasn’t necessary. Dianne Wilkerson, by that point, had helped put Wilburn in touch with Stephen Miller, of McDermott, Quilty & Miller, to assist with the license. Wilkerson was also holding up legislation that included pay raises for the Boston Licensing Board, and she kept holding it up until she had assurances from the board that Ron Wilburn would get his liquor license. Once that happened, the three-member board received a 42 percent pay raise; Pokaski’s pay alone jumped from $60,000 to $85,000 a year. The board was so quick to approve Wilburn’s liquor license — the public debate lasted mere seconds — that it overlooked the fact that Wilburn no longer even had an address for his club. “I have never heard of that happening,” says a longtime lawyer who specializes in liquor licenses. “Whenever I’ve done an application, you have to provide an address and…a floor plan.” Pokaski retired in June of last year and, despite repeated attempts, could not be reached for comment. The acting board chairman, Michael Connolly, as well as Stephen Miller, say Wilburn had claimed when the liquor license was granted to him that he hoped to have a lease for his club at the address 15 Melnea Cass Boulevard, which at one point was listed as the proposed site. Connolly adds that “it’s very uncommon” but probably not unprecedented for the Boston Licensing Board to grant a liquor license without an address.

But the irony in all this is that Wilburn didn’t need to bribe Wilkerson, either. As far back as January 2007 — before Wilburn ever met with the FBI — the Boston Licensing Board told Wilburn that all he needed to do was change his club’s floor plan from a nightclub to a more traditional restaurant, and the license was his. In the end, that’s what Stephen Miller had Wilburn do, and that’s what the board approved. “It was pretty easy,” Miller says. “It was actually one of the easier [approvals] we’ve had.”

THE FBI EVENTUALLY DUMPED WILBURN. Agent Scott Robbins testified that by the end of 2007, the bureau wanted to widen the scope of the investigation. To do that it needed undercover agents, not helpful civilians.

It’s tough to tell what’s become of this widened investigation. Robbins testified that a third public official had been under investigation for quite some time, but no one has yet been arrested or indicted. It may very well be that the FBI couldn’t get its man (or woman). But it’s also worth noting that Wilkerson’s arrest on October 28, 2008, occurred during — and that Turner’s indictment soon followed — the trial and conviction of former Boston FBI agent John Connolly. Connolly, of course, was a gangster with a badge, leaking information to the infamous Whitey Bulger, who then used that information to kill a potential witness. At the very least, it was fortuitous timing for the FBI that a splashy public corruption case just happened to be competing for media attention with the trial of a former rogue agent.

WHEN I TRACKED DOWN WILBURN after his testimony, he told me only that he would call me. And, sure enough, after Turner was convicted, I did get that call. “I am a man of my word,” Wilburn said. But he made it clear that he wouldn’t discuss anything. He was only working with writers who would pay him for the privilege. I laughed.

“My pro bono days are over,” he said.

With additional reporting by Jason Schwartz