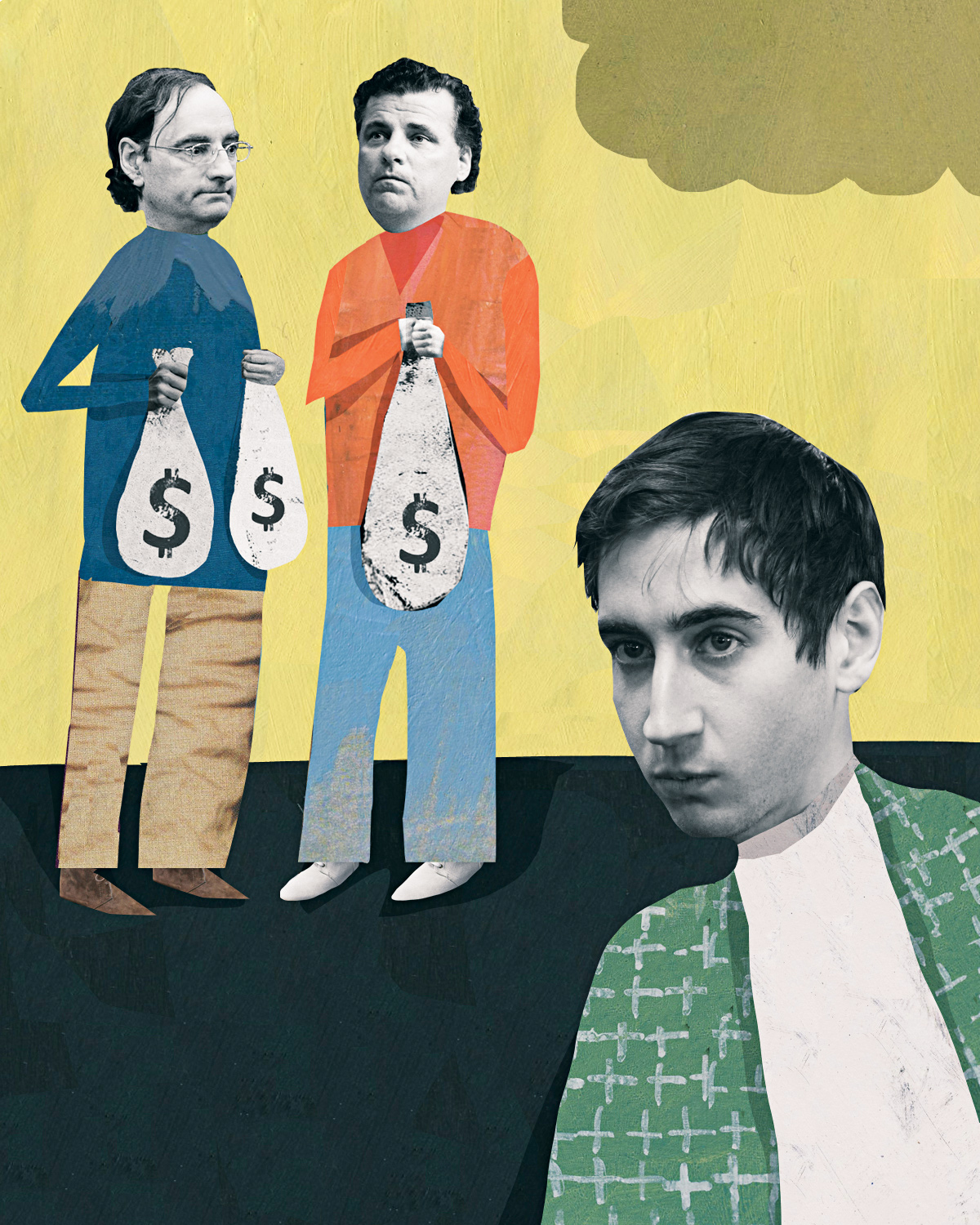

When Crime Doesn’t Pay

Illustration by katherine streeter. photographs by

REUTERS/CJ Gunther/Pool/Landov (Rockefeller); AP Photo/

J. Pat Carter (Weeks); AP Photo/Wendy Maeda (wheeler)

Snooki wrote a book. So did the Situation. Kate, she of plus eight, has done three. Anyone who’s sniffed fame, it seems, is liable to publish these days. That fact apparently weighed heavily on Middlesex Superior Court judge Diane Kottmyer in December, when she sentenced Adam Wheeler, the man who faked his way into Harvard. Kottmyer gave Wheeler 10 years of probation — and prohibited him from profiting from his story.

Fair enough. But why, then, has any mobster who’s ever gotten within 5 feet of Whitey Bulger — Kevin Weeks, Eddie MacKenzie, et cetera — been allowed to cash in with his own tome detailing crimes much more heinous than duping the world’s greatest university?

Restricting a criminal from making money on his story seems like it could violate the First Amendment. And, in fact, the legal reasoning behind Wheeler’s sentence is a bit messy. In a case related to the infamous Son of Sam murders, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1991 that a New York law barring criminals from profiting from their crimes was too broad and therefore unconstitutional. So Massachusetts repealed a similar law on its books. Four years later, though, the state’s Supreme Judicial Court said judges may apply the condition in sentencing, because individual judges dealing with individual cases can be more precise than broadly applied laws are. “Once you’re convicted, there are many types of restrictions that can be imposed on you during your term,” says Jonathan Albano, a First Amendment specialist at Bingham McCutchen.

In the end, it comes down to the judge and the prosecutor. The Middlesex DA typically asks that criminals in all high-profile cases be barred from profiting from their stories, says spokeswoman Cara O’Brien. In Suffolk County the policy is similar, though spokesman Jake Wark says such cases are rare. When the Suffolk DA did request that the prohibition be applied to Clark Rockefeller, the wannabe Brahmin who kidnapped his own daughter, the judge denied it. (Judge Kottmyer didn’t respond to calls for comment about Adam Wheeler.)

As for why judges have let mobsters sell their stories, First Amendment lawyer Harvey Silverglate has a theory: “Maybe the judges make the assumption that they can’t write to save themselves,” he says. “It’s probably a form of intellectual profiling. I’m not kidding. I don’t think it occurs to judges that some of these guys might write books about their careers in crime. Whereas it’s perfectly obvious that this Adam Wheeler character is a candidate to write a book.”

Even if Wheeler were allowed to pump out a memoir, Albano figures the faker extraordinaire would have a bigger problem. “Nobody would believe it, anyway.”