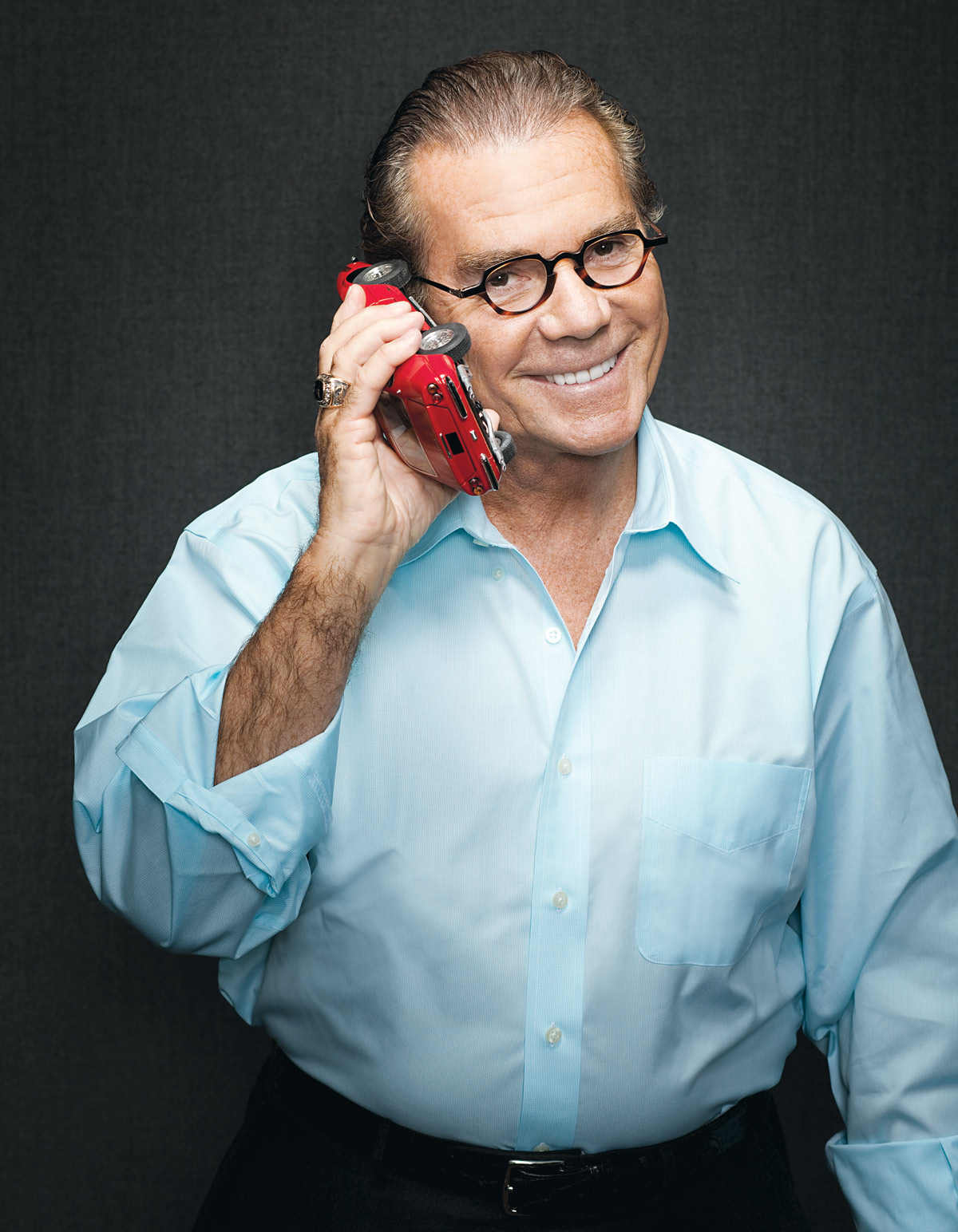

Wheels of Fortune

AT A GATHERING OF BMW DEALERS in South Carolina, Herb Chambers found himself at the same table as a competitor he’d heard was having financial troubles. Chambers has 47 car dealerships these days. Or maybe it’s 46. It’s difficult to keep track because he’s constantly adding to his automotive empire. In all things, Chambers moves quickly when he sees what he wants. He’s been known to close a deal on a new location in half an hour, and now, sitting across the table from his weakened rival, he sensed the chance to close another.

“I was thinking, I want to buy his store,” Chambers recalls. “I knew they were struggling.” So he offered the guy a ride home to Boston on his corporate jet. “I’m thinking, If I can get him on my plane, I can talk to him. Maybe by the time we land, he might do something.”

“What time is your flight?” he asked the car dealer.

“Oh, 6 o’clock tonight.”

“We have wheels up at 1:15,” Chambers replied. “Come back with me.” The man thought about Chambers’s offer for a while. “No,” he said at last. “I don’t think I better do that.”

Win or lose, Chambers has a fondness for bold action. His collection of dealerships is now the 13th largest in the country. Or it could be 12th. (“I feel like General Custer and he’s Sitting Bull,” says his friend and competitor Jim Carney, who owns the Bernardi Auto Group. “He’s got me surrounded.”) Specific calculations of what Herb Chambers actually owns are problematic, because, when it comes to Herb Chambers, ownership is a fluid concept. Pretty much everything in his possession will eventually be sold, and anything he wants in his possession will eventually be purchased, only to be later sold…a kind of self-perpetuating cycle of buying and selling that, when you factor in his forever-extending empire of outside business interests, makes a precise accounting of his belongings at any particular moment essentially meaningless. (“I don’t know how many companies I have,” he says. “There are probably 65 or 75 different companies — I know that we do 65 or 75 tax returns.”) However you add it up, Chambers has a lot to keep track of. He sells approximately 45,000 automobiles a year — one out of every five in eastern Massachusetts — and services another 40,000. He employs 1,900 people, has $300 million or so worth of inventory sitting on his lots on any given day, and, according to this magazine, had a personal fortune in 2006 of nearly $2 billion. But that was five years ago, and with all his buying and selling since then, who really knows how much he’s worth today?

So yes, there are a lot of important details for Herb Chambers to keep straight. And the one that’s been vexing him lately has to do with the 40,000 apples he gives away every year at his service shops. As a diabetic, he prefers to promote healthful snacking, but the gesture has created an unexpected headache. “What’s driving me crazy,” he says, his voice rising, “is I like the red apples — and at the dealership, you have to polish them — but some of them are still putting out green!” What’s this? The billionaire with 46 or 47 car dealerships is upset because his people put out the wrong color apples? Yes, and so much so that he finally called together some of his top execs to get to the bottom of the situation. “I’m going over this with people in management. So I guess we’re going to go with 80 percent red and 20 percent green. I guess some people like green.”

FIGURING OUT WHAT PEOPLE LIKE and then rushing to provide it to them faster and with better service than they imagined has been the life’s work of Herb Chambers.

He’s the high school dropout who got his start selling photocopier supplies out of his car and over time made himself into one of the wealthiest and most powerful people in New England. And he’s built that incredible success by sweating one tiny, seemingly insignificant detail after another. One of his favorite words is

“perfect,” as in, “I’m not happy unless it’s perfect,” or, “My customers expect it will be perfect.” But nothing ever is, and that can lead to Chambers getting twisted up with anxiety about the slightest problems, about the stuff the other guy doesn’t even know exists.

Like right now. He’s supposed to be giving a tour of the gleaming 120,000-square-foot Lexus store he opened a few years ago in Sharon — the place looks like a chic Vegas hotel, with soaring ceilings, lots of marble and glass, and flat-screen-crowned urinals — but he keeps getting distracted by the slightest sign of clutter or wear. Descending the grand staircase that connects the sales and service floors, he sighs and scoops up a scrap of crumpled paper. In the shop, he frowns at a smidge of grease along the wall. “I try to be as carefree as I can,” he says, “but there is this constant thing that it’s got to be right, it’s got to be perfect. I try to calm myself down when I’m talking to our employees, because otherwise they’re going to think I’m crazy. You know, ‘When is this guy gonna let up?’”

Yes, when? At 69, there doesn’t seem to be much left for him to achieve. He’s rich and his legacy is secure. Harvard brings him in to talk shop with the business students. He’s a must-get for Boston charity fundraisers. He has a beautiful girlfriend. He lives on the 12th floor of the Mandarin Oriental, and in a tastefully renovated farmhouse in Connecticut. He takes lunch with Herald publisher and president Pat Purcell and dinner with his friend Herb Lipson, who owns this magazine. (Chambers spends $1 million a month on advertising and, full disclosure, some of it goes to Boston magazine. Then again, some of it goes to just about every media outlet in the region.) “I’m the luckiest person you’re ever going to meet,” he says again and again. “And I’m not kidding.”

But then there’s that other side, the intense competitiveness and drive for perfection that are almost certainly responsible for everything he’s accomplished — but that have probably kept him from fully enjoying the ride. “It’s a curse not to be able to relax,” he says. “It does make you unhappy.”

“I keep telling him, ‘Slow down, it’s time to slow down,’” says Al Abate, his friend of more than 50 years. “He says, ‘You’re right, but I can’t.’”

CHAMBERS MAY NOT EXACTLY be unhappy right now, sitting in the Kiss 108 radio studio, but this interview is going far from perfectly, and the smile on his face is slipping. He’s appearing live on the Matty in the Morning show to promote a TV Diner charity event he’ll be hosting days from now at that Lexus dealership in Sharon. Sitting at a tall desk, Chambers is surrounded by host Matt Siegel, his sidekick Billy Costa, and Jenny Johnson, the producer of TV Diner. As always, he’s well tanned, and he’s wearing a dark suit, a lavender tie, and big radio headphones.

Though Chambers is among friends — he socializes occasionally with Siegel and Costa — the interview has taken on an edge, mostly because Siegel revels in starting trouble. “How’s that yacht of yours?” the host asks him. Chambers, who lives a lifestyle of extreme luxury but can’t stand the thought of coming off as ostentatious, responds with silence. “I know I’m making you uncomfortable,” Siegel says, “and I apologize for it, but I’m so fascinated by it. You’re a self-made man, and that’s the American dream.”

Chambers jumps at the chance to change the subject, launching into the story of how he borrowed $500 from his mother to start the copier business he eventually sold to a Fortune 500 company, then parlayed that windfall into his auto kingdom of today.

“Now he has 47 dealerships, a jet, a yacht, and a helicopter,” Siegel says. The station cuts to a commercial break and everyone moves to a lobby adjacent to the studio. “From selling paper out of your trunk to where you are — that’s an incredible story,” says Costa.

“That’s what I wanted to get at in there,” says Siegel. “It’s not like Ernie Boch Jr., where you were born into it. He did it the easy way.”

“Some days I wish I could do it the easy way,” Chambers replies.

Siegel says it’s hard to believe Chambers could still care one way or the other how many cars he sells.

“Absolutely!” Chambers says, slamming his fist into his palm. “You’ve got to get out there and beat them every day! It’s just like you.”

“No,” Siegel responds. “I need it. You don’t need it. What do you need, another helicopter?”

“Well,” Chambers says, “you want to win.”

Siegel, who likes cars, asks about the collection of automobiles Chambers keeps at his Connecticut home. He has several vintage Ferraris and one of only 65 street-ready McLaren F1s in the world.

“You keep them on a turnstile?” Siegel asks.

“No.”

“Ernie Boch has them on turnstiles.”

Chambers’s look goes serious. He has a complicated relationship with Boch. Not with the man, actually — he doesn’t know him well — but with the idea of the man. Though Boch, with only a handful of dealerships, poses no danger to Chambers’s bottom line, he’s the only dealer in New England who rivals his name recognition. Chambers would never admit it, but this fact may bother him. There’s also the way Boch has taken the stereotype of the flashy car salesman and cranked it up to 11, like a guitarist in his rock band, Ernie and the Automatics, maxing out the volume for an extended solo. Boch can come across as a kind of nouveau-riche buffoon, and you get the feeling that Chambers, a fellow big-spending, high-profile car dealer, worries his image takes a hit by association. Finally, there’s Boch’s deceased father, Ernie Boch Sr., a legendary car salesman. Long before Chambers conquered automobiles, he used to sell copiers to Boch Sr. “When I got my first dealership,” Chambers recalls, “someone talked to him and said, ‘What do you think about this Herb Chambers coming into the car business? You think he’s going to be a threat to you?’ He said, ‘No, never. He knows nothing about the car business and he’ll invest 100 million bucks, he’ll lose it all, and walk away.’ I have great respect for him, but he didn’t have very much for me. He thought that I was just a guy with some money.” Standing in the radio station, you can almost see Chambers formulating a response to Siegel: I could put my cars on turnstiles if I chose to. I just choose not to.

Before he can say anything, though, Siegel slaps him on the shoulder. “I’m just kidding!” he barks. “You always fall for that.”

HERB CHAMBERS GREW UP dreaming big. When he was a toddler, a photographer for the old Boston American captured him at the beach, scooping up water with a metal can. The photo caption described him “bailing out the ocean.” Chambers still has the clipping. “Typical Dorchester kid,” he says, laughing. “Conventional plastic pail and shovel? I had a paint can.”

Chambers was born in a two-family Dorchester home owned by his maternal grandmother. His father was a commercial artist, and his mother was a homemaker. “My father was very easygoing,” he says, “and my mother was the taskmaster.” When Chambers hit his teens, the taskmaster started charging him rent, $15 a week. His brother and two sisters got the same deal.

To pay the rent, Chambers lied his way into a job at Stop & Shop when he was 13. (You were supposed to be 16.) He collected the shopping carts in the parking lot. Far from drudgery, it was fun. “It was almost a game with me, to see how few carriages I could have sitting out in the parking lot,” he says. The ultimate goal: “no carriages out there that somebody didn’t have their hands on.”

He excelled at the supermarket, earning a series of promotions and raises. School, however, was a different matter. He ended up dropping out during his senior year. It was 1959, he was 17 years old, and he needed something to do. So he joined the Navy.

While serving in the Florida Keys, his job was to supervise the cleaning of fighter jets. The guys working for him were generally lazy and uninspired. But Chambers was intrigued by the challenge of motivating his shiftless charges. “I couldn’t control their pay, but I could control when they showed up and when they left,” he says. He worked out a contest in which the two hardest workers got extra time off. Soon everyone was hustling. “So it was fun; it was a game,” he says. “It was a puzzle.”

In 1963 Chambers got out of the Navy and moved back in with his parents, working for a couple of months at a rough-and-tumble bar in the South End his mother had inherited from a deceased brother. The place was dingy, the mirrors so discolored from cigarette smoke that the barflies could scarcely see themselves. Chambers, though, was undaunted. “I was going to take this bar and turn it into Mistral.”

Before he got the chance, however, he was out of a job. One Sunday after he’d been at the bar for two months, he got a call from his mother.

“Yes, Mother?” he said.

“Don’t you ‘yes, Mother’ me,” she snapped. “You’re fired.”

“Fired? For what?”

“You were supposed to open the bar today,” she said, insisting that his name was on the schedule. He tried to explain that it was his father — also named Herb — who’d failed to show up, but his mother wasn’t interested.

“Don’t you give me any of this crap,” she said. “You’re fired, that’s it.”

Chambers tells the story with a laugh, but it’s clear the memory pains him. “She was so tough,” he says. “I was so crushed by this that I went home and I basically had just Navy clothes and three or four pairs of jeans. I threw it all into a bag and brought it to my sister’s house in Braintree.”

CHAMBERS ALWAYS keeps one residence or another in Boston. He’s lived at the Mandarin since it opened in the fall of 2008, and before that he was in a 9,000-square-foot single-family townhouse in the Back Bay. But for the past 32 years, home for Chambers has been his farmhouse in Old Lyme, Connecticut, near the confluence of the Connecticut River and Long Island Sound. That’s where we’re heading now as we cut south in his sleek black helicopter, moving at 140 knots, 1,500 feet above the ground. It’s a spectacular late-autumn morning and the sun is shining magnificently, breathing a few dying moments of brilliance into foliage that, at season’s end, has gone mostly dull. It’s a breathtaking sight, the kind Chambers experiences all the time. This is his regular commute, lifting off from the helipad atop his Mercedes dealership in Somerville and touching down 38 minutes later right outside his front door in Connecticut.

As the helicopter passes through the area of Foxwoods casino, Chambers mentions that he’s an investor in a nightspot there called Shrine, one of three projects by the restaurateur Ed Kane that he’s put money into. Backing Kane is a rare instance of Chambers joining someone else’s deal. Most of his net worth is tied up in his car companies, though he is “very heavily invested in the market. I don’t choose stocks on my own. I have Goldman Sachs and I have Bank of America and they make those decisions for me.” So why work with Kane? “I know him personally,” Chambers says, “and I know his character.” Kane, like so many of the people Chambers is drawn to, is a self-made man. He started with little, worked as a bartender, attended Harvard, and eventually hit it big. Chambers spends most of his time with family — he has a son from a marriage that ended in divorce after 13 years — and a small circle of very close acquaintances, most of them up-by-the-bootstrappers like himself.

As we near Chambers’s house, a wide stretch of river comes into view. “It’s a great boating area,” he says. “It’s really one of the main reasons I stay here.” Chambers is passionate about boats. In addition to an array of personal crafts, he owns a 188-foot yacht, Excellence III, that summers in the Mediterranean, winters in the Caribbean, and is chartered to some of the richest people in the world. The boat — which will be sold once its successor is completed in October — charters for $500,000 a week.

We begin circling down and the helicopter comes to rest on a helipad in front of the garage where Chambers’s vintage cars are kept. We hop out and Chambers, in white cargo pants, a linen shirt, and suede loafers with no socks, leads the way up to his house. Outside stands a rust-colored statue of Richard Nixon holding his head in his right hand and flashing a peace sign with his left.

Like the place at the Mandarin, the farmhouse’s décor is casually elegant. It’s very high-end, yet there is nothing flashy about it. As we walk through the house, though, Chambers stops at something that looks like an anomaly — a painting he commissioned a few years ago depicting a group of attractive young people frolicking on Shell Beach in Saint Barts. After the artist sent his initial sketch, Chambers told his secretary to inform him that “their boobs are too small” and should be made bigger.

We complete the tour of the house and walk down Chambers’s vast front yard of rolling green, past his two life-size fiberglass Clydesdale horses and through a fence that leads to the parking lot of a marina he owns at the end of the property. Out on the dock bobs a gorgeous 44-foot Rivarama, a sporty Italian boat Chambers bought during a recent trip to Europe. The Rivarama was shipped to Connecticut six weeks ago, and today it’s going to be put into storage for the winter.

We jump onto the boat, and Chambers takes the wheel. He eases out into the Connecticut River and guns the engines once we enter Long Island Sound a few minutes later. The boat surges forward, leaving behind it an enormous wake. Half an hour later, we enter a marina in Westbrook, Connecticut, and Chambers expertly positions the Rivarama alongside the dock. We step off the boat and are met by a man named Paul, who captains Chambers’s personal yacht.

Paul drives us to another part of the marina, where the 83-foot yacht has been put away for the season in a heated hangar that seems only inches longer than the boat itself. We walk around and climb a ladder that brings us to the rear deck. The yacht is spotless, but Chambers is focused on the gleaming wood that lines the stern. Paul says he’s just finished polishing the area. “I was noticing there’s a bare spot on the varnish,” Chambers says, frustrated. “I was wondering where that came from.”

AFTER GETTING FIRED by his mother, Chambers was suddenly in need of a job. So he picked up the Globe and found an ad for a copy-machine repairman. Though he didn’t know what the machines did, he managed to talk his way into the position. The pay was $75 a week, plus commission on any service contracts he could sell.

The other repairmen would have six or seven service calls backed up, but Chambers, in his early twenties, was determined he’d never be a single call behind. “I never took breaks,” he says. “There was a place that used to sell hot dogs for a buck down on Broad Street. I’d run and get a hot dog down the street with my toolbox, heading to fix the next copy machine.”

It didn’t take long for him to realize, though, that the real money was in the service contracts. He was surprised to discover how effective he was at selling the insurance plans. Soon he was covering two territories, and the service contracts were rolling in. The suits back at the home office in Illinois started asking his boss about the kid who’d sold more contracts than anyone in the country. Was he a sales guy? No, Chambers’s boss told them, a repairman.

Chambers was quickly transferred to the sales team. Now his job was to sell copier supplies, primarily paper and toner. That sounded easy enough, but there was one thing standing between him and all the money he hoped to earn: He was painfully shy. It was no big deal to sell contracts to people who’d already given him a natural opening — they’d invited him in to fix a copy machine — but the notion of cold-calling strangers was excruciating. So he signed up for a Dale Carnegie course to learn how to speak to people when he was nervous.

It wasn’t long before his training was put to the test. One day Chambers was making cold calls in the Garment District. He entered a building on Kneeland Street and walked up a set of stairs to an office where, behind a pane of glass, an old woman was answering the phones. “Hi,” he said. “I want to talk to somebody about supplies for the copier machine.”

“No, no,” the woman said. “We’re not interested.”

Chambers kept up with the sales pitch. Suddenly, he heard a howl from a man in an unseen office: “We don’t want any!” Chambers quickly left.

A month later he returned to the office, climbed the stairs, and tried again. He asked the old woman if he could leave her samples. Again, a man yelled, “We don’t want any!”

“Can you come out here for a second?” Chambers called out. “I want to show you something.”

At that, the man came roaring out of his office, stormed over to Chambers, and proceeded to kick his briefcase down the flight of stairs. “Now get out of here,” he screamed, “and don’t come back!”

“It was one of the low moments of my life,” Chambers recalls. “Somebody doing that to me, treating me like dirt.” But as he began picking up the papers that had scattered from his tumbling briefcase, he realized what he had to do. “This is a moment I have to win,” he said to himself. “You don’t give in.” He marched back up the stairs and asked to see the man again. Amazed by the kid’s moxie, the guy placed a big order — and offered Chambers a job. He declined.

Chambers was making plenty of money as it was. He sold more in a day than anyone else was doing in a week. So when his supervisor resigned, Chambers was promoted to the position. He’d been a salesman for a month.

Al Abate recalls being dumbfounded the first time he visited his old buddy from the Dorchester streets. “The secretary referred me to his personal secretary,” Abate says. “He had this fancy office and big desk. I told him, ‘This is unbelievable.’”

“I’m quitting,” Chambers said.

“What? You’re quitting? You’re crazy!”

“If I can do it for them, I can do it for myself.”

Chambers gave his notice, intent on starting his own company. But a non-compete clause meant he’d have to work at least 100 miles from Boston. So he formed a company called A-Copy America and opened for business next to a barber shop in Hartford. Abate, who’d gone down with him to scout locations, told him he was crazy. Chambers didn’t care. “He just believed in himself,” Abate says.

The strategy was simple: Find a tall building, take the elevator to the top floor, and work your way down, office after office. “And after I had hit all those offices downtown, then I would hit the florist shops, I’d go to car dealers and places like that.”

Chambers likes to say he’s the luckiest person he’s ever met. If that’s true, one important bit of fortune for him was the timing of his entry into the copier game. Not long after the launch of A-Copy came the introduction of affordable copy machines that businesses could buy rather than lease from the manufacturer. Soon Chambers was hawking copy machines along with copy supplies.

He started selling Minolta copiers in the early ’70s and before long was the world’s largest Minolta dealer. Then he became the largest Canon dealer. Sharp and Ricoh were big brands for him, too. At its height, Chambers says, A-Copy employed 1,400 people in 36 offices.

In 1983 Chambers sold A-Copy to the Alco Standard Corporation for a reported $80 million. He spent two years working for the publicly traded conglomerate, but he hated it. There was no passion, no competitive zeal, no urgency to win. So one day after spending half an hour in a Connecticut Cadillac dealership, he walked out with more than a car. He’d decided to buy the entire dealership.

CHAMBERS IS BEHIND THE wheel of what just may be the hottest car on the road today, a black Bentley GT Supersport that goes for around $240,000. “You know what’s great about it, too?” he says. “It’s not flashy.” (He’s right, by the way. If it’s possible for a quarter-million-dollar sports car to be understated, this is the one.)

We pull out of his Somerville Mercedes dealership and onto McGrath Highway, setting off for Beacon Hill. Chambers is attending an event tonight to raise money for the preservation of mounted patrols in the Public Garden. He frequently walks the park in the morning, and has been hearing that budget cuts might mean the end of the patrols. “I can’t even imagine — somebody should get involved and maybe people can contribute money to keep those horses here,” he’d told his girlfriend, Melissa Lees, who then suggested that he might be just the man. “That’s on Sunday,” he says. “On Monday, I’m going through my mail, and I open up an envelope and there is a picture of a horse.” It was an invitation to the fundraiser.

The event is being held in the Parkman House, which overlooks the Common and is the mayor’s official reception hall. It’s an older crowd, about 50 people dressed formally and mingling across two adjoining rooms with high ceilings, hardwood floors, elegant rugs, and a bar.

Everyone knows Chambers. He smiles graciously, offering self-deprecating jokes and easy conversation. It’s hard to believe his shyness once led him to take a Dale Carnegie course. He explains later that he decided as a young man, “I am going to become somebody I’m really not. I have to be confident and carefree and just happy-go-lucky, and that’s what I’m gonna be, an actor. And I’ve done it for so long that I’ve become that person.”

Standing by the bar, Chambers spots someone he knows. “Hi, Tom!” he bellows.

“I’m Tom Kershaw,” the man says. “I own the Hampshire House, Cheers….”

“I know who you are!” Chambers says heartily.

“But more importantly,” Kershaw says, “I’m a customer. I just ordered one of the golden Mercedes.”

“Did you really? I hope you bought it from me.”

“That’s what I’m talking about!” Kershaw says. Kershaw’s wife, Janet, leans in. “I just saw Ernie Boch,” she says with a grin. “I thought that was kind of funny.”

Boch is standing against a wall about 15 feet away, fiddling with his cell phone and looking uncomfortable. Though everyone else is in suits and ties, he’s dressed for one of his band’s gigs, with long hair and a goatee, a black coat, black sneakers, and a thin black sweater over a black shirt. There’s no real reason why he and Chambers should say hello, but everyone in the room seems to be watching. Chambers keeps chatting with his small group and Boch turns away to say something to someone near him. The moment passes and the two men do not speak.

“Maybe he didn’t see me, you know?” Chambers says as we walk back to the Bentley. “I mean, I was talking to somebody and my plan was to go over and say hello to him and next thing, I think he was gone.”

Later that night, we meet a number of Chambers’s employees for dinner at Strega Waterfront. Denise Devoe, a corporate controller who’s been with Chambers for nearly 20 years, brings up the time a decade ago that the big publicly traded companies began approaching Chambers about buying him out. He had 10 or so stores, had all the money he could ever need and, at the time, was nearing his sixties. Rumors were rampant that he was going to sell.

“So anyways,” Devoe says, “he has a big meeting with all the managers, and he goes, ‘I’m not selling because I’m not going to do Burger King next.’ So that’s why he’s still selling cars. I’ll never forget that.”

Chambers says he never seriously considered selling for a minute, but the attention was flattering because it validated his success. “I always thought I was a one-trick pony,” he says. “Being able to do what I did in the copier business and to be able to replicate that is hard to do.”

Then again, Chambers seems to have a gift for willing what he wants into existence, like deciding that the mounted patrols in the Public Garden should be saved and then, the very next day, hearing from the fundraisers. “It sounds spooky,” he says. “What happens is, I always have these moments when I think about something and the next day it happens. It just happens to me again and again.”