Love the Kennedys and Nobody Gets Hurt

On January 17, the New York Times ran a story about The Kennedys, the eight-part miniseries that the History Channel had mysteriously decided not to air — after spending a reported $15 million on its production. The Times had been running articles on the miniseries for a year, detailing — and to a significant degree, stoking — the controversy swirling around the project. But as I read reporter Dave Itzkoff’s story “Dramatizing Camelot,” I began to suspect that it had very little to do with The Kennedys and quite a lot to do with the Kennedys.

The History Channel, Itzkoff reported, had spiked the drama “after an unsuccessful yearlong effort to bring the miniseries in line with the historical record.” Unnamed sources described The Kennedys as inaccurate and sordid. Soon the show would be painted as a right-wing hatchet job — co-created, as it was, by Joel Surnow, one of Hollywood’s most prominent conservatives. (There’s not a lot of competition.) Surnow is buddies with Rush Limbaugh, Roger Ailes, and Ann Coulter, and his most famous work, the long-running drama 24, depicted torture as an effective antiterrorism tool. Now, according to an emerging narrative, his new show was out to take down America’s most iconic liberal family.

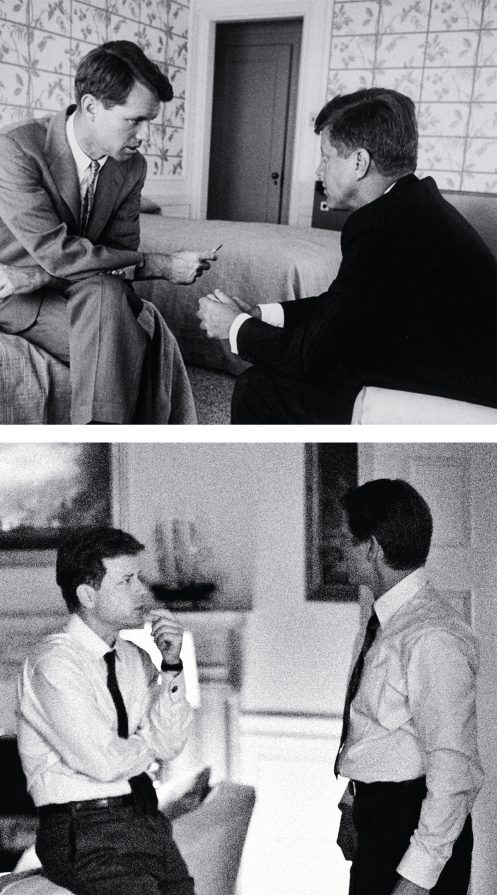

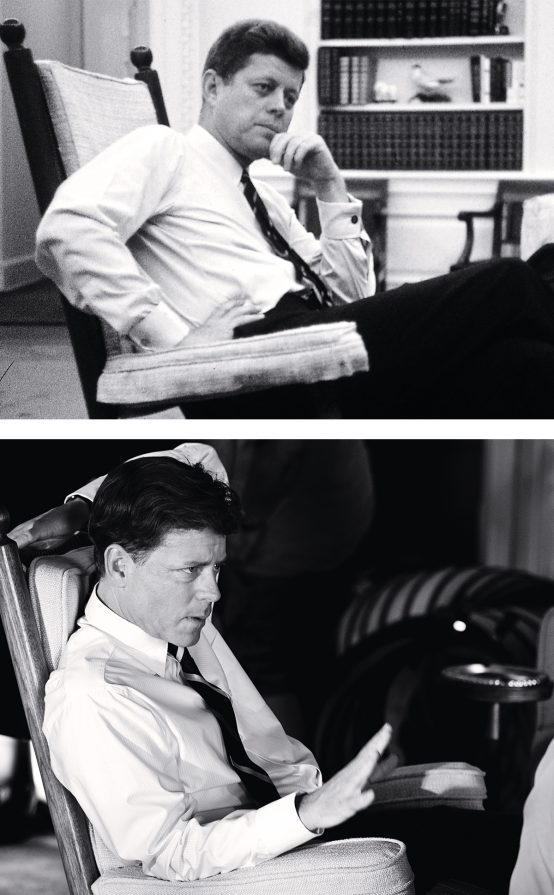

A few weeks later, I managed to get an advance copy of The Kennedys, and what I watched was no conservative hit job. Yes, the miniseries presented patriarch Joseph Kennedy, the main character, as massively ambitious, philandering, a bit corrupt, and a Hitler sympathizer — but it also detailed his deep devotion to his sons, and the almost unbearable pain he suffered from the tragedies that befell them. It wasn’t a flattering portrayal, but it was certainly a defensible one. Add in the depiction of JFK as a man whose idealism was blended with more base desires, and what you had were characters that seemed influenced more by Oprah Winfrey than Rush Limbaugh.

I was starting to get the feeling that the story in the Times had actually been part of a smear campaign, something planted by anonymous sources who didn’t want the show to ever see the light of day. And that felt like a story I knew firsthand.

A little more than 10 years ago, I decided to write a book about John F. Kennedy Jr., my boss at the political magazine George. I admired John, and wanted to write something that would reflect that. But within weeks, sleazy, false, and untraceable rumors started popping up in mainstream media outlets, while behind-closed-door efforts were launched to sabotage a book that hadn’t even been written. Within months, both my career and my reputation were in tatters.

I’ve never talked much about that time in my life; it’s a hard story to tell, and I don’t like to discuss it. But reading about the miniseries made me think that the time had come. I wanted to know: What happened to The Kennedys, and was it the same thing that had happened to me?

For most of its existence before the past year, the History Channel was a pretty sober place. Part of the Arts & Entertainment Television Networks, which is jointly owned by NBC Universal, the Hearst Corporation, and the Disney/ABC Television Group, History was known for serious, well-made documentaries, most of which seemed to focus on wars and Adolf Hitler. The network likes to boast about the numerous awards its programming has won, and, in fact, pretty much the only controversy in its 16 years of existence involved the 2003 documentary The Guilty Men, which suggested that Lyndon Johnson was involved in John. F. Kennedy’s assassination, provoking outrage from, among others, Lady Bird Johnson. In response, History commissioned an impressive panel of historians, which ultimately concluded that the documentary was indefensible. The channel offered a public mea culpa — a letter of apology to Lady Bird, a ban on subsequent showings, and a commitment to strengthen its review procedures.

For the most part, though, History was an oasis of earnestness in the increasingly anything-goes cable landscape. But for the past several years, a team of executives led by CEO Abbe Raven and president Nancy Dubuc have been remaking the network, adding more aggressive programming such as Ax Men, about macho loggers, and Pawn Stars, which is like Antiques Roadshow meets Jersey Shore. History just notched its best February ever, and among men ages 25 to 54, a group beloved by advertisers, it was the top-ranked cable channel.

A Sample of Controversial Scenes from The Kennedys

The Kennedys was to be another watershed in History’s evolution: the network’s first scripted drama. Despite the conspiracy theories that would later arise, it came about in a typical TV way: History vice president Dirk Hoogstra asked Jonathan Koch, president of Asylum Entertainment, if he was interested in developing a miniseries and suggested the Kennedys as a topic. (Like war, the family generates big numbers.) Koch pitched the idea to Joel Surnow, with whom he’d worked on other projects. Surnow liked the idea and called his friend Stephen Kronish, a liberal who admired Jack and Bobby Kennedy.

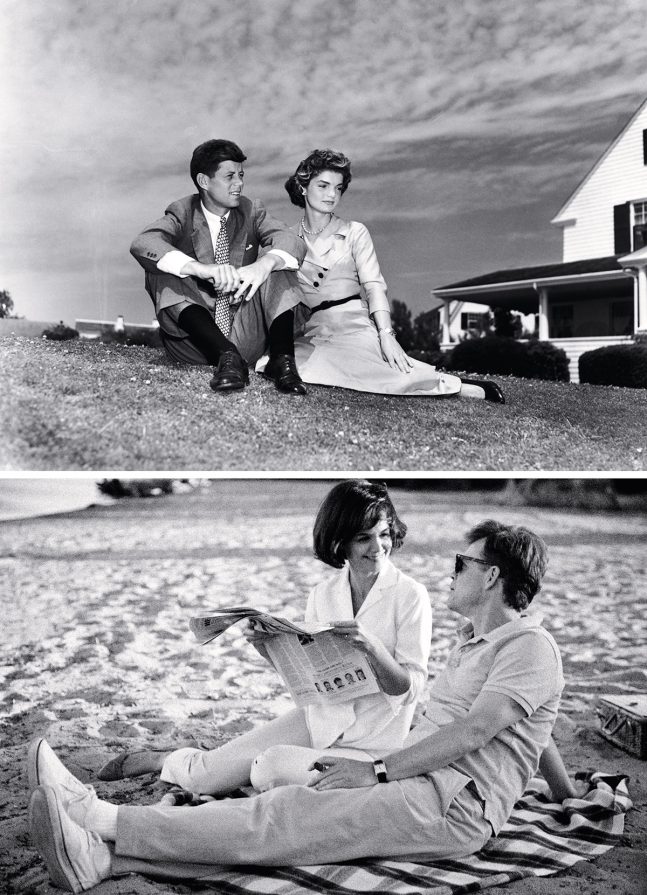

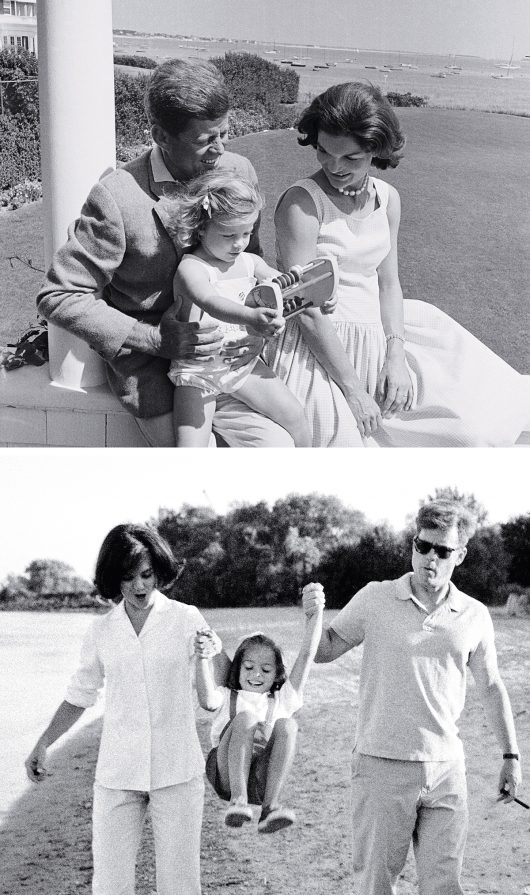

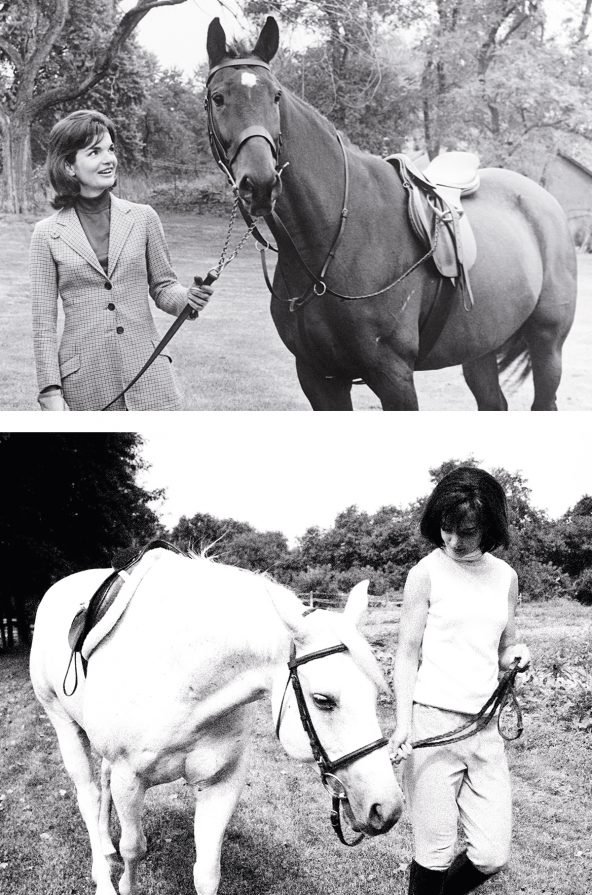

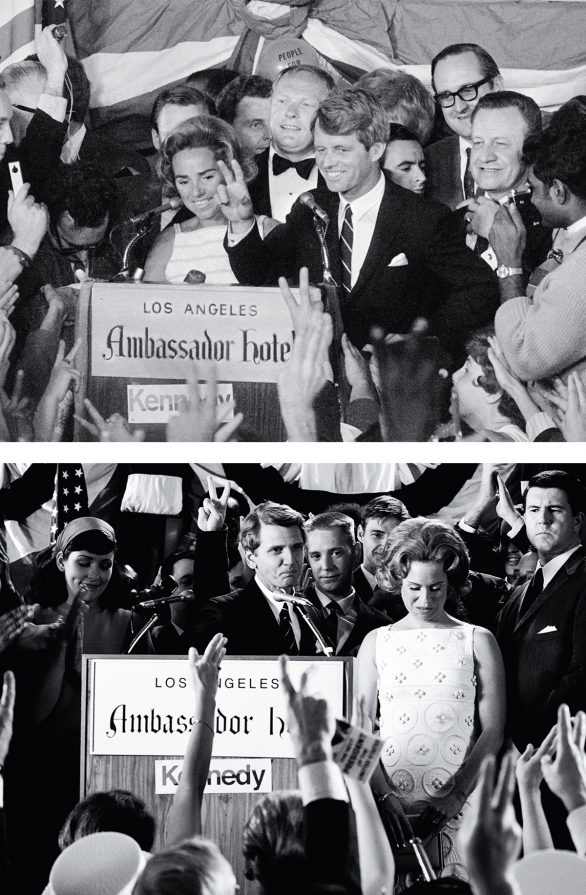

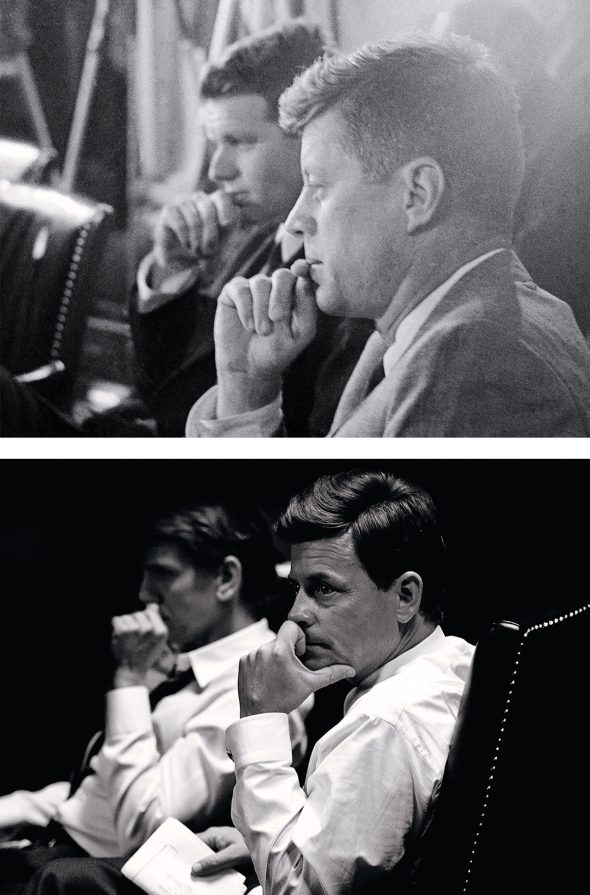

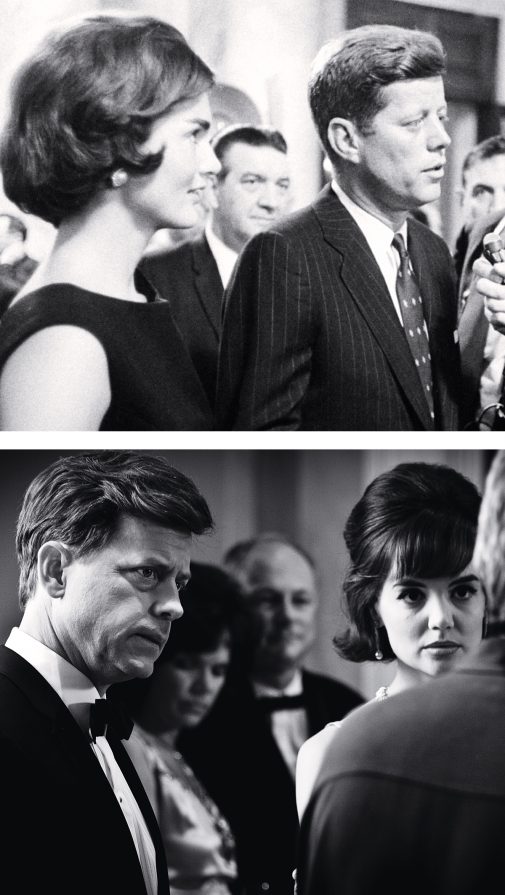

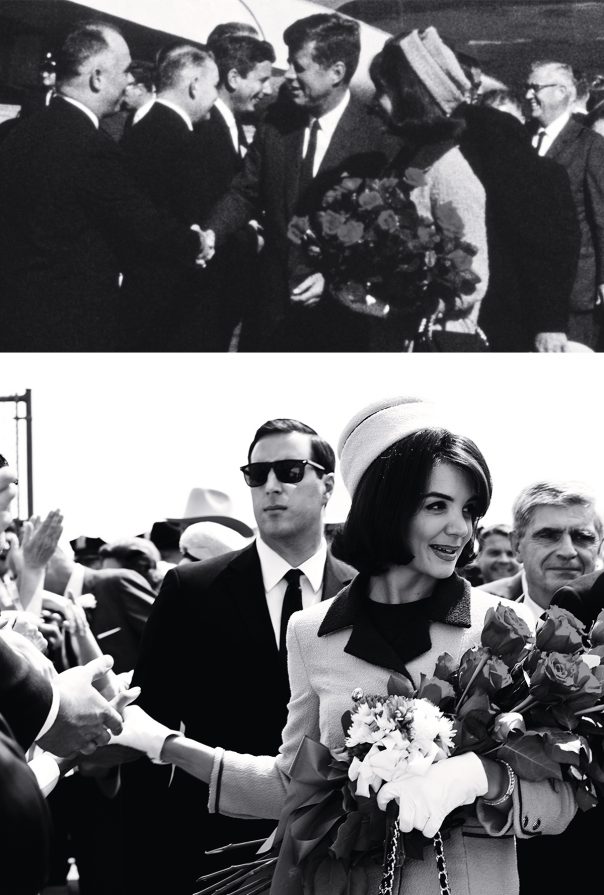

The two men worked out a pitch for History, and in August 2008 they submitted an outline, which Nancy Dubuc was enthusiastic enough about to commission a full script. Once she received that script, History ordered seven more installments, and in December 2009, Dubuc gave the green light to cast and film the eight-hour production. “She was the one who shepherded the project,” Surnow said. In April 2010 History announced a high-profile cast that blended acting chops — Tom Wilkinson as Joe Kennedy, Barry Pepper as Bobby — with Hollywood star power — Greg Kinnear as JFK — and a bit of tabloid catnip (Katie Holmes, a.k.a. Mrs. Tom Cruise, as Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy). “We basically put together a wish-list cast, and we got it,” Surnow said.

But long before shooting commenced, The Kennedys had created at least one very dogged enemy: the liberal filmmaker Robert Greenwald. The Los Angeles–based Greenwald is the founder of the Brave New Foundation, an activist organization that makes left-wing protest films under his Brave New Films moniker. Labeled a “guerrilla” documentarian by the New York Times Magazine, Greenwald has made movies attacking Walmart, the healthcare industry, and Rupert Murdoch, among others. His campaigns also help to raise money for his foundation.

Greenwald told me that a friend in the entertainment industry gave him an early script, and as he read it, he grew outraged by its focus on the personal lives of the Kennedy family members. “I was shocked and angry and unbelieving that the History Channel would agree to such a clear piece of political propaganda,” he said. So Greenwald decided that, one way or another, The Kennedys script had to be, in his word, “fixed.”

In 1995, I was one of a small, enthusiastic group of writers, editors, and businesspeople who helped John F. Kennedy Jr. found his magazine, George. I signed on as a senior editor and worked at the monthly for the next four years, eventually working my way up to the role of executive editor. (John, of course, was editor in chief.)

It was a dream job for me, a combination of compelling subject matter and the chance to work with a boss who was not only fascinating in his own right, but also warm and funny and immensely likable. Nearly all of us who worked with John felt the same way. You couldn’t possibly understand what it was like to live his life, of course, and so you couldn’t really know John; his status in American culture was unique, his experiences far removed from anything the rest of us had known. But he handled himself with grace and an unexpected (to me, anyway) humility, and all of us who worked at George for any length of time came to feel protective of him. You couldn’t help it.

When John died in July 1999, I was devastated. We all were. To have someone we cared about so much yanked away as if by the flip of a switch…to have John and his wife and sister-in-law found at the bottom of the ocean.

That pain was difficult for people who didn’t work at the magazine to imagine, because they didn’t know how personal our relationships with John were. (Most didn’t even realize that he came to work every day.) But the grief was overwhelming. For many of us at George, it was the most profound loss we had known.

I couldn’t bear the empty office next to mine. I had to leave, and I knew it. But I stayed for five more months to help put out the magazine and support my colleagues until a new editor could be found. It wasn’t easy. At first we responded to John’s death with a determination to carry on. But as the months passed, the reason for doing so became less clear, and that energy turned into a lingering malaise. Emotionally exhausted but still deeply sad, I left just before Christmas 1999.

I took some time off and traveled solo in Australia; on the Great Barrier Reef, I learned to scuba-dive. But I couldn’t stop thinking about all that had happened. It bothered me that the remembrances I’d read after John’s death were polite but often damned with faint praise; many were entirely dismissive of his magazine. One writer for Salon concluded, “From his salute to his father through his career at George, JFK Jr.’s triumphs were mostly style over substance.”

I thought that maybe I could tell his story from a more informed perspective. And so I decided to write a book about John and his magazine.

When I returned from my trip, I contacted a literary agent, Joni Evans of the William Morris Agency. Some of her clients had written for me at George. Tough but fair, Joni was someone I’d liked working with. And Joni liked my idea. Obviously, it had commercial potential. But also — and this mattered to me — she thought that my concept could be a good book, a useful book. She encouraged me to write a proposal, and in March 2000 we sent it to about half a dozen publishing houses. All expressed interest, but we chose Little, Brown, a house with an outstanding literary reputation. Publisher Sarah Crichton, who’d signed Malcolm Gladwell and was known for working closely with her writers, offered $750,000 for the project, American Son.

Prior to Little, Brown announcing the deal, I got a call from Craig Offman at Salon, who’d freelanced for George. He’d heard I was writing a book, and wanted to ask some questions. I told him I’d be happy to talk, but I had to call him back. (I was on jury duty.) A couple of hours later, when I did, he didn’t answer.

The next day, his story appeared online: “Former George Editor Peddles JFK Jr. Memoir.”

That was bad enough, but Offman soon followed up with a more sarcastic look. It was headlined “John-John, I Kinda Knew Ye…and I’m going to make a bundle writing about you.” Someone had leaked him a copy of my proposal, and he quoted selectively from it to make me look pompous and duplicitous. Offman wrote that I described myself as “Kennedy’s closest colleague,” which was doubly wrong; I wasn’t, and had never claimed to be.

Key Players in the Controversial Show The Kennedys

Maybe — probably — I shouldn’t have been surprised at such hostile press, but I was. Surprised, and worried. But that was nothing compared with what would come.

There is a certain machiavellian side to the Kennedy family, an aspect completely at odds with the public image, and it has manifested itself again and again since JFK’s assassination on November 22, 1963. The Kennedys and their allies have been trying to shape and control how the president and the family will be remembered ever since.

Whether it’s behind-the-scenes threats, purging of embarrassing records from the archives, or decisions about who gets library access and who doesn’t — what’s become clear to me over the decades is that the family will lay siege to a project of which it disapproves, marshaling a campaign of public denigration and private pressure, none of which can be easily traced back to the source. For the Kennedys, the point of historiography is not to search for truths but to buttress the family’s political and cultural legacy — or, to put it more simply, to keep people from writing things about them that they don’t like.

It all started with Jacqueline Kennedy’s determination to sculpt the memory of her murdered husband, beginning within hours of his death. Consider the story of her near-destruction of historian William Manchester (pictured).

In early 1964 Jackie and Bobby Kennedy reached out to Manchester and asked the writer to pen a sanctioned account of the assassination. Manchester had written an admiring book about JFK, 1962’s Portrait of a President, and so, as has been reported, Jackie and Bobby arranged for Harper & Row to commission a book with the cooperation of both Kennedys. Manchester agreed to the project, and wound up interviewing both Jackie and Bobby Kennedy for hours.

But when the writer turned in his manuscript, Jackie decided it was too personal — Manchester disclosed the fact that she smoked, for example. In a 2009 Vanity Fair article, Sam Kashner writes that Jackie pressured Manchester to change the manuscript. Charming at first, she soon warned Manchester that “anyone who is against me will look like a rat — unless I run off with Eddie Fisher.” Months later, according to Kashner’s article, Manchester was still refusing to alter his work, so Jackie turned up the heat: “I’m going to ruin you,” she told his Harper & Row editor, Evan Thomas. Eventually, she filed an injunction to block the book’s publication on the grounds that, since she’d agreed to be interviewed by Manchester and had helped him set up other interviews, she had “the absolute right” to control the book.

The lawsuit was ultimately settled out of court, and The Death of a President was published in 1967 with minor changes. It earned glowing reviews and enjoyed huge commercial success. But because of the Kennedys’ original agreement with Harper & Row, the family controls the fate of the book. They have allowed it to go out of print, and aspiring readers of one of the finest works on JFK’s assassination must now troll the Internet for used copies.

The episode with Manchester was the beginning of a pattern for Jackie. Her operating principle: If you cooperate with a writer, you have the right to control him. And if you can’t control him, don’t cooperate with him. Writers who violated Jackie’s rules paid a price.

In 1975 Washington Post executive editor Ben Bradlee authored Conversations with Kennedy, a book that most readers found deeply flattering to the late president. Before the book was finished, Bradlee, once a friend and confidant of both Jack and Jackie, sent the manuscript to Jackie, but she didn’t like it; it was too much about Bradlee, she told him, not enough about her husband. She also disapproved of his inclusion of JFK’s cursing. (“He used ‘prick’ and ‘fuck’ and ‘nuts’ and ‘bastard’ and ‘son of a bitch’ with an ease and comfort that belied his upbringing,” the editor wrote of the president.) Bradlee had no interest in making changes. After all, JFK had agreed that Bradlee could publish their talks five years after Kennedy left the White House.

“I saw Jackie twice after that conversation,” Bradlee wrote in his 1995 autobiography, A Good Life. Bumping into her in 1976 as he was entering a party and she was leaving, Bradlee stuck out his hand and said hello. “She sailed by us without a word.” Later, when Bradlee was vacationing in St. Maarten, Jackie and her children were, coincidentally, staying in the very next cabana. “For a week,” Bradlee wrote, “we seemed to be staring at each other on the beach, but never ran into each other until one night, when we almost collided as we left our cabana to go up to the restaurant for dinner. From 12 inches away, she looked straight ahead, without a word, and I never saw her again.”

The one Kennedy scion who lived long enough to actually have the means to control the depiction of his own legacy would probably have disapproved of such behavior. When former New York Times reporter Adam Clymer was researching his book Edward M. Kennedy: A Biography in the mid-’90s, “Kennedy was very helpful,” Clymer recalls. “I forget how many interviews we did — something like 18.” And Teddy, unlike Jackie, never asked for editorial control.

Not that Ted Kennedy cooperated with every book — he didn’t — but if there are examples of him trying to block the publication of a book — and so many have been written about the Kennedys, one can’t rule it out — I couldn’t find them. One possible reason for his more fatalistic sensibility, says an author who has written about the Kennedys but wishes to remain anonymous for fear of jeopardizing future access, might be that historians could not shatter Ted Kennedy’s mythology; with Chappaquiddick, he’d done so himself. “Part of Teddy’s maturity was that he didn’t want to be mythic,” this writer says. “He really understood his own humanity and his own fallibility…unlike the other Kennedys, who I don’t think had as much self-awareness, maybe because they didn’t live long enough.”

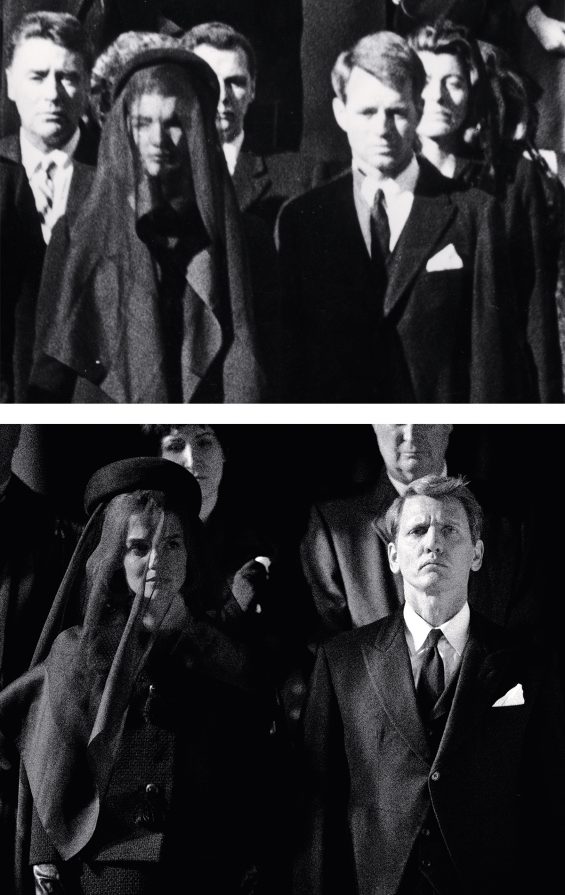

The Kennedys: Life Imitating Art