Elizabeth Warren: Stumped

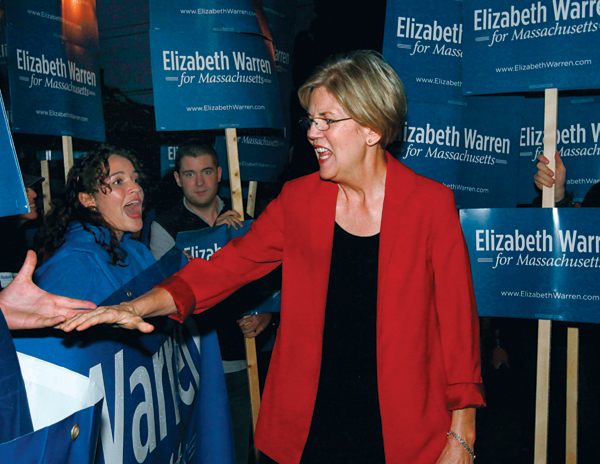

Warren meeting supporters at a campaign event in Lowell. (Photo by Elise Amendola/AP Images)

This may be Warren’s first run for office, but that’s not to say she lacks political experience. “She’s not a babe in the woods in Washington circles,” says Adam Levitin, a former Warren student who’s now a Georgetown law professor (he’s teaching at Harvard this fall). “She has long-standing personal relationships with senators.”

Warren first drew the attention of Washington insiders with the 1989 publication of As We Forgive Our Debtors, a book she coauthored with Westbrook and Sullivan that showcased their groundbreaking consumer bankruptcy research. In 1995, she became a senior adviser to the National Bankruptcy Review Commission, which was created in response to the skyrocketing rate of bankruptcy filings at the time. “Credit card companies had decided they wanted to rewrite the bankruptcy laws,” she recalls, and they were lobbying to make it more difficult for people to file. For nearly eight years, she worked to keep bankruptcy as a viable option for middle-class debtors. She testified before Congress and submitted briefs to the Supreme Court, arguing that bankruptcy can keep working families from “falling off the cliff” into poverty. Through that process, she came to understand that her ability to convey difficult concepts simply and intelligently could become a political asset.

Melissa Jacoby, a protégé of Warren’s who served as a staff attorney on the review commission, remembers watching her explain bankruptcy policy to Senator Ted Kennedy in the late ’90s. “After a pretty short meeting, Senator Kennedy understood how these issues affected the people that he cared about in the commonwealth of Massachusetts,” she says. “He was ready to fight the good fight.”

In time, Warren began to explore not just bankruptcy law, but also what caused people to file in the first place. In 2003, she and her daughter, Amelia Warren Tyagi, a former management consultant, published The Two-Income Trap, which argued that the escalating costs of ?housing and education have led to the hollowing-out of the middle class. Warren became the Cassandra of consumer advocacy, railing against credit-default swaps and subprime mortgages, which she contended were preying on hardworking American families. “It is impossible to buy a toaster that has a one-in-five chance of bursting into flames and burning down your house,” she wrote in the journal Democracy in 2007. “But it is possible to refinance an existing home with a mortgage that has the same one-in-five chance of putting the family out on the street.”

After the 2008 financial crisis, Warren was hailed as a visionary. Senator Harry Reid tapped her to chair the bipartisan Congressional oversight panel set up to ensure that every dollar of the $700 billion in TARP funds handed to the banks was accounted for. Warren produced in-depth monthly reports, appeared on television at every opportunity, and regularly hosted public discussions that became skewering sessions of Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner. It was her work on this panel—her strident criticisms of Wall Street, the Fed, and Geithner alike—that made her famous.

“I was impressed not just with her knowledge, but her ability to help do things politically with her common sense,” says Congressman Barney Frank, who watched as she navigated through Washington with increasing confidence. The two became close allies during his work on the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act, which helped establish Warren’s brainchild, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Frank eventually counseled President Obama to name Warren head of the CFPB: “I said to him, ‘You should appoint her. If the Republicans filibuster her they’ll make her a hero, and it’ll be easier for her to run for the Senate.’”

It was an open secret that Warren welcomed taking control of the agency, but her hard-charging ways had left many in Washington—Republicans and Democrats alike—believing that her ideological zeal made her unfit for the role. “Will Elizabeth Warren be as effective as a bureaucrat as she is as a guest on The Daily Show?” Neil Irwin wrote in the Washington Post.

Warren continued her attacks on Geithner, who by then was said to be openly opposing her nomination. In his new book, Bailout, Neil Barofsky, who served as inspector general for TARP, writes that he’d expected Warren to play nice with the Treasury secretary in the hopes of securing the appointment. “But she just lit him up…. I thought it was a remarkably principled act, the exact opposite of what any other person in Washington angling for a high-profile job would have done.”

Ultimately, Obama did not appoint Warren, angering the thousands of supporters who’d petitioned for her to get the job. That left Warren looking for another outlet to push policy change. Fortunately, one was waiting.