A Curator Explains How an Exhibit at the MFA Comes to Be

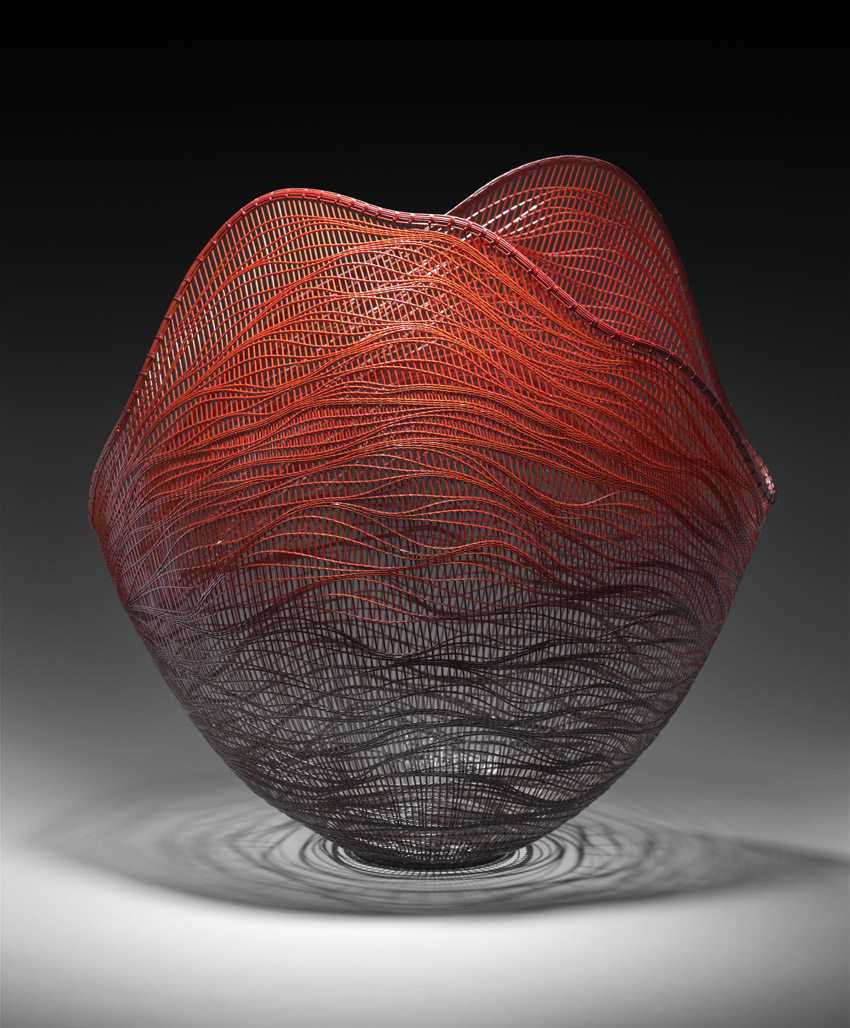

“Fire,” by Yamaguchi Ryūun is a basket made of Japanese timber bamboo. (All objects part of the Stanley and Mary Ann Snider Collection. Photos provided by MFA Boston.)

With nearly 450,000 works of art in their collection, the Museum of Fine Arts has an immeasurable challenge: acquiring, organizing, and turning these pieces into stories for Boston’s art lovers to enjoy. In comes the curator to tackle the daunting task.

“All along the way—and this is true of any exhibition—you’re constantly having a dialogue between curator, designer, and all the people involved, because we’re making adjustments until the door opens,” says Anne Nishimura Morse, the MFA’s William and Helen Pounds Curator of Japanese Art.

Works don’t magically appear on the walls of an exhibit. It is easy to forget about the artistic choices made in the arrangement of the collections themselves.

To gain a better understanding of the curation process, we talked with Morse about one of her latest exhibits, “Fired Earth, Woven Bamboo: Contemporary Japanese Ceramics and Bamboo Art,” which opened yesterday at the MFA.

Where did the idea for this exhibit come from?

This particular exhibition celebrates a gift of 90-something pieces that the [Stanley and Mary Ann] Snider family has given to the museum. It really puts us on the map for being the center of contemporary Japanese art. It gives people the opportunity to see works with a little bit of context. That was the genesis for the exhibition.

Have you worked closely with the Sniders? Are they still part of a project now or do they give their gift and then give you free reign over the exhibition?

We work very closely with all of our collectors, and the Sniders are people I’ve known since I first came to the museum in 1985, so I’ve had a very close relationship with them. They’ve lived with the pieces, so they know the pieces better than I would. They’ve been collecting these pieces over the years, so we talk to them very much about why they purchased certain works and how they’ve appreciated them. Those are some of the things we wanted to bring out in our display as well.

Are there any stories behind the pieces that came out of working with the Sniders?

There is a set of plates that I know for Stanley Snider have been very important objects. They acquired them in the 1980s from a dealer in New York. They loved the whole experience of learning from her, going to talk to her—the whole acquisition of them was very exciting. It was a time in the Sniders’s lives when they were going to Japan frequently, trying to learn about the Japanese aesthetic, so this set of five plates are ones that you will see in the center of the gallery.

Mary Ann Snider is a very strong woman and I think this collection features a number of works by very strong female artists, of which Stanley is very much supportive. It’s a very different take than you would have seen in Japan in the 19th century. For us to have works by female artists is a very important addition to our collection.

What was the thought process in the arrangement of the gallery itself? Did the Sniders have any influence on that?

In their home, they lived with the pieces, but they’re not necessarily having to relay a story. My job as a curator is to make sure people enjoy the art, but also understand what they are looking at.

What we did for this exhibition is, in the center of the room, we looked at major artists and how the approach to Japanese ceramic art and basket weaving has changed and evolved in the 20th century. Then in the back you’ll see a combination of ceramics and baskets, without much labeling material at all so [visitors] can just appreciate them and see the variety. So we’ve really got two approaches going.

How have you shaped the gift into a story about Japanese art?

We are known for our Japanese art collection. We have the largest and, arguably, most important collection of Japanese art outside of Japan. So for us, it’s very important that people understand that it’s not just a traditional view of Japan, but that Japanese art is very vibrant. I think that with this gift, one can see the very creative ways that artists are working. They’re not always working in traditional materials; they’re also working in very architectural forms, very inventive forms. It’s a transformation. It’s a culture that is pushing the limits.

Is there any specific way that you want people to enter the exhibit and view it?

This gallery is particularly challenging because there are six different ways to enter it, so it has to work that it draws people in no matter where they enter. Working with any design, it’s important to make sure that, in every vista, someone walking down the hall or coming up from another gallery says, “I want to stop here.”

How do you deal with the floating museum-goer who doesn’t read wall text and prefers to meander through exhibits? How do you prepare for this type of visitor as well?

You can’t assume that anyone’s going to read the labels. Even if they’re going to read some labels, they’re not going to read them all for sure, so you pick the most visually powerful works that you can find. As they walk through the gallery, they say, “Wow, that’s beautiful.” They stop; they look at it. Then, if they want to learn more, that’s a bonus.

How many hands have to touch the exhibit before it goes up, from beginning to end?

We have an exhibition project manager, who makes sure everyone is coordinated and works together. We have our exhibition designer, whom I’ve worked with closely on a number of shows, but for this one it’s been every day, tweaking everything. We have conservators for every type of work, so there are object conservators, textile conservators, painting and traditional Asian format conservators. Then there are the mount-makers and people who help us install. There are people who design labels, then people who edit my labels. We have a video that features two different artists so there were people involved in the video-making. I have a colleague in Japan, Kazuko Todate, who helped with the catalogue. Of course, with the catalogue came catalogue editors and designers. Then there are lighting people who have worked on the show, and the last step is getting the gallery cleaned after all is done. Any show here is a large production and a very collaborative production.

And how long did the entire process take, from the time that the last exhibit was in the gallery until now?

There’s a lot of prep time that goes into this, so I think the last exhibition closed at the end of September. It also has to do with timing of other things in the museum, so some of the other works needed to be installed, some shelving needed to be added, lighting needed to be changed. The actually install time: we started installing on Monday [November 4] we and finished on Friday [November 8]. Once we’re in the gallery, it goes very quickly, but there are a lot of things that need to get done before then.

Do you have any personal favorite piece in the exhibit?

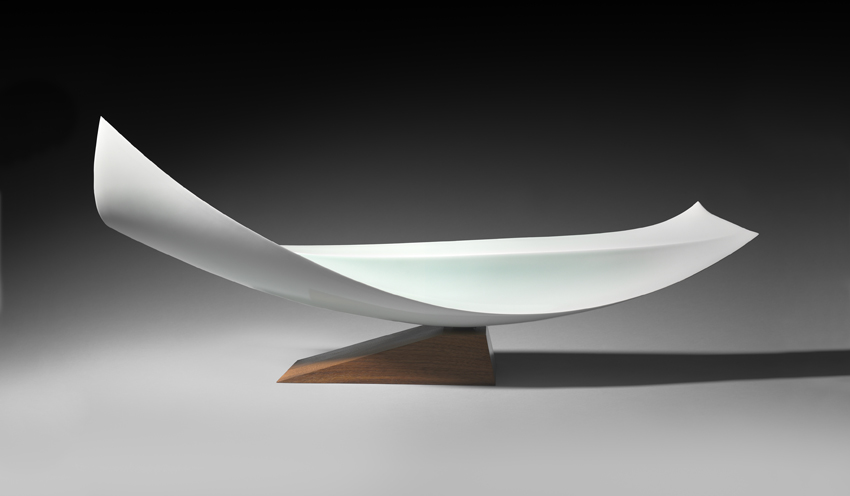

One of the pieces that I love (because I know the artist really well) is a ceramic piece that we borrowed from the Sniders before they gave this gift, a piece by Fukami Sueharu. It’s a celadon piece called “The Moment” (shown below). That piece is just perfection. The balance of it is beautiful, the surface of it is beautiful, and it’s definitely in one of the access points to the gallery, so you’ll see it when you come in.

What will happen to the pieces after the show is done? How does a gift to the museum work as opposed to something traveling?

Most of the pieces that the Sniders have given are outright gifts to the museum, while others are promised gifts. So the promised gifts, at some point, will go back to them until they formally decide to give them to the museum. Most, about 80 out of the more than 90 of them, have already been formally given to the museum. They will stay with us and you will see these objects making their way into some of our permanent displays after the show.

“The Moment” (Shun), a porcelain piece created by Fukami Sueharu, is one of Morse’s favorites in the exhibit.

This porcelain piece, “Vertical Flower,” is by Sakurai Yasuko.

Another Japanese timber piece, “Red Flame,” is by the artist Morigami Jin.

“Shell,” stoneware by Koike Shōko.

“Flight,” Japanese timber bamboo and rattan, made by artist Torii Ippō.

This bulbous stoneware piece, “Bud Casing II” by Fujino Sachiko, departs from traditional Japanese ceramics, exemplifying the aims of the exhibit.

“Fired Earth, Woven Bamboo: Contemporary Japanese Ceramics and Bamboo Art” is open now through September 8, 2014, at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, 465 Huntington Ave., 617-267-9300, mfa.org.