Q&A: Nick Cave at the ICA

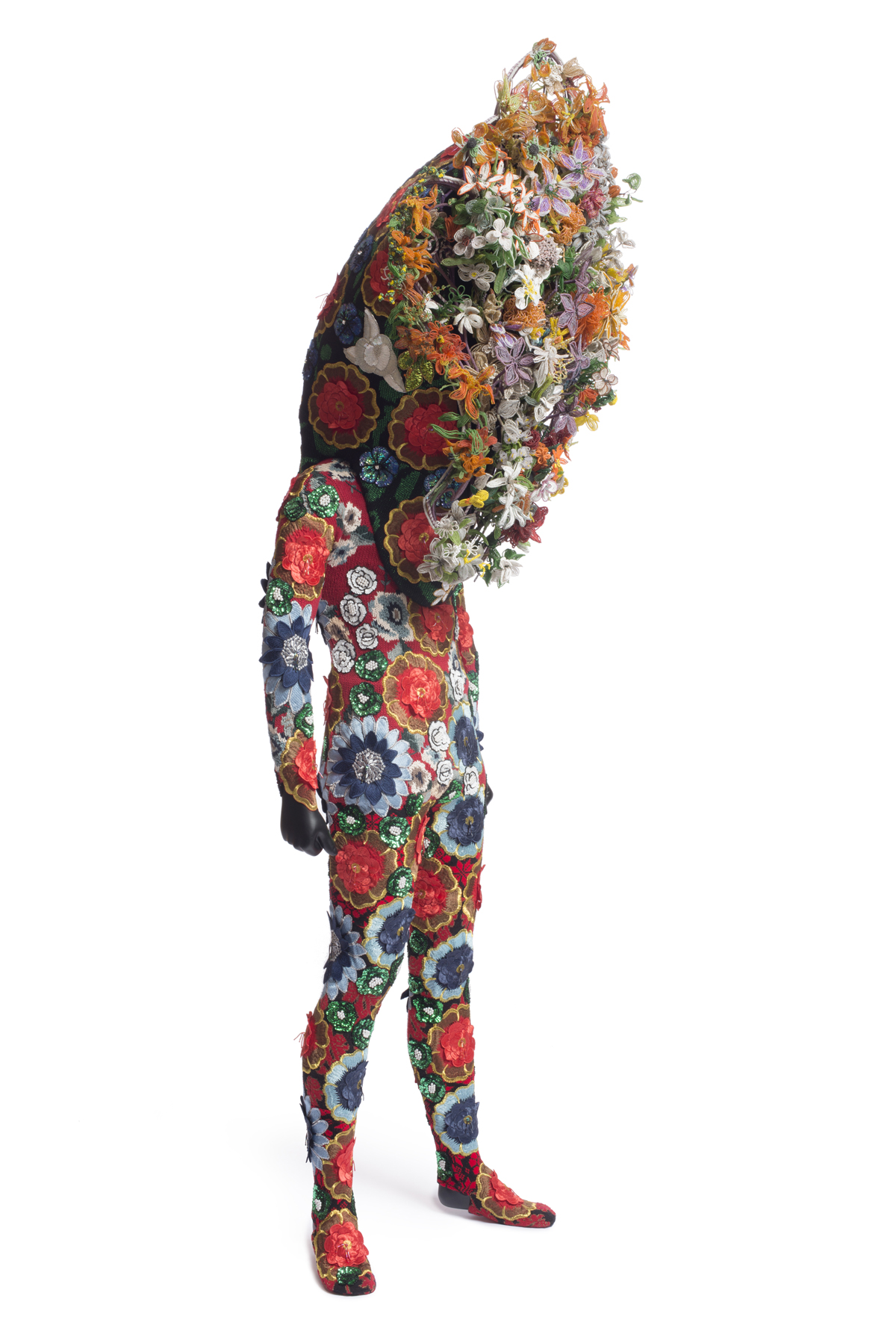

Soundsuit made of mixed media including crochet blanket and sequins, 2013. (Courtesy of Nick Cave and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. Photo by James Prinz Photography.)

Nick Cave is known for the unquestionably unique, ornate Soundsuits he creates, but his show, opening at the Institute of Contemporary Art on Wednesday, February 5, pushes new boundaries of critical art.

The exhibition will include multiple Soundsuits as well as a video component to display the performative aspect. Cave has paired this with a new body of pieces examining the role of the dog in both classical painting and popular culture. For these works, Cave sits ceramic dogs on vintage settees, surrounding them with elaborate metal structures interlayed with birds, flowers and crystals, which he also uses in a triptych “painting.”

“The show is going to be a show that will really pull the community in,” Cave explains. “I’m curious to create an experience for the audience there to immerse themselves in, so I’m excited.”

Read on for a little background on the artist, his practice, and the works on display at the ICA.

Where did this all begin? Where did your art background come from?

My first Soundsuit was in 1992 in response to the Rodney King incident, the [Los Angeles] riots, so that really was the beginning of that project. Prior to that, I was doing these large, constructive sort of paintings. So in a way I’m going back to this period of work of these sort of constructive paintings, yet, at the same time, moving myself forward.

How did something like a Soundsuit come out of the Rodney King incident?

It’s interesting because my work shifted 90 degrees. I was not making any type of work that was like this work before. I think that it comes out of my interest in performance, my interest in embellishment, adorning the surface of something. The act of building complex environments led me to take all of this and apply it to the body—looking at the body as a carrier of an idea. As I created this sculpture, I didn’t even realize I could put it on until it was done. So then, when I finished it and put it on and started to move in it, it made sound. Then, moving in it and hearing it started to make me think about the role of protest, opening up the possibilities of thinking about it. Then, a suit of armor as a sort of protection, and then creating something that was very scary, that was very foreign, that was this hybrid. As time has gone on, I really think that I’m an artist with a social conscience, and the Soundsuit started to hide gender, race, and class, forcing you to look at something without judgment. We tend to want to categorize something or find a place for understanding it, and here there is not; its origin is very foreign in terms of looking at ceremonial costumes that, perhaps, could lead you in a particular way of thinking about an object.

What is your process now? Do you mostly show pieces you have already exhibited, mostly Soundsuits, or primarily new creations?

For the most part, when it’s a solo show, I try to create new work. This provides a platform to experiment that allows new ideas to be created. But again, what does this mean in terms of this transition; what is it that I’m going to carry over into the new work that allows the viewer to understand and know that it’s a Nick Cave? I think this is where the transition starts to find its way into a new sort of thinking.

What pieces are included in the new part of the show that you have created specifically for this exhibit at the ICA?

That show consists of a triptych that is 8 feet by 24, so it’s pretty big. It’s really what I look at as this garden plot, it’s a landscape that is looking at early spring—spring meaning that it’s all in bloom—but then it’s been affected by frost, which is all of these found crystals that saturate the entire surface. It has a lot of depth—really rich, really textural—and you really are immersed by this interesting landscape. It is a metal work that is embellished with found flowers, porcelain birds, figurines of sorts, afghans, and very densely populated with bead work and those crystals. Then you have three Rescue pieces, which are these found Victorian furniture pieces, and on these furniture pieces are these dogs, which are all ceramic dogs that I found. My research really came out of the conception of the dog in Renaissance painting and, at the same time, looking at a contemporary, sort of urban, hip-hop language—that, “You’re my dog” sort of merging these two ideas together.

Do you work on one specific piece at a time, or is it more of a multi-work process?

In the studio, we may have three to five pieces happening at the same time. Once we complete these pieces, we literally move them out of the studio. So, we never have them around us where it could hinder a particular way of thinking and making; it’s always removed. It’s always this flux and flow in the studio, and I don’t really sketch anything. I’m really just responding; it’s a call-and-response approach, which really allows the studio to constantly be in flux.

Where does your inspiration most often come from?

The inspiration really comes out of one object, the agitator, that becomes the central core. I’m at flea markets and thrift stores and antique malls. I don’t really ever know what that may be that may get me excited and curious about its potential, but what I see when I connect with this type of object is the multiple ways in which it could be read, so it’s the multiple readings of the object. I want there to be a reflection of its function, but yet, there’s this sort of shift of, “Is it that?” It’s a renegotiating the role of it in this new form.

Is there any overall message that you hope to get across, or do you really just want people to appreciate your art aesthetically?

I think that, with the Soundsuits—again, with my role as an artist with a social responsibility—I’m still looking at hiding identity, race, and class, and forcing you to look at it without judgment. It’s, sort of, looking at these utilitarian tools or devices that have a significant purpose or function, and then again, flipping it upside down and renegotiating. I think that really counts within the times in which we are living in today, the fact that we have to wear many different hats, being able to shift ourselves, to put ourselves within a place of how we may be existing in the world today. There is this moment within the work where, somehow, you can’t identify with its essence, but you’re still not sure why you’re pulled into this work. There is something that you associate with, but it’s still very unfamiliar.

You’ve shown all over the world. Do you keep the audience who will be viewing it in mind when you create an exhibit?

I really produce work and it’s not that it’s for any particular person or region, it’s how can I create work that becomes universal, somehow we can all associate with, or engage with? I try to keep it really open to interpretation, but I think, as an artist, I have to also think about, “What is my role of getting you taken on this journey? What are elements that may pull one into this work?” Once that hook is there, you have the liberty to continue on the journey.

Soundsuit made of mixed media including sequins and beads, 2006-2012. (Courtesy of Nick Cave and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. Photo by James Prinz Photography.)

Nick Cave will be showing at the Institute of Contemporary Art, February 5-May 4, 100 Northern Ave., 617-478-3100, icaboston.org.

This interview has been condensed.