Director Malcolm Rogers Reflects on His Time at the MFA

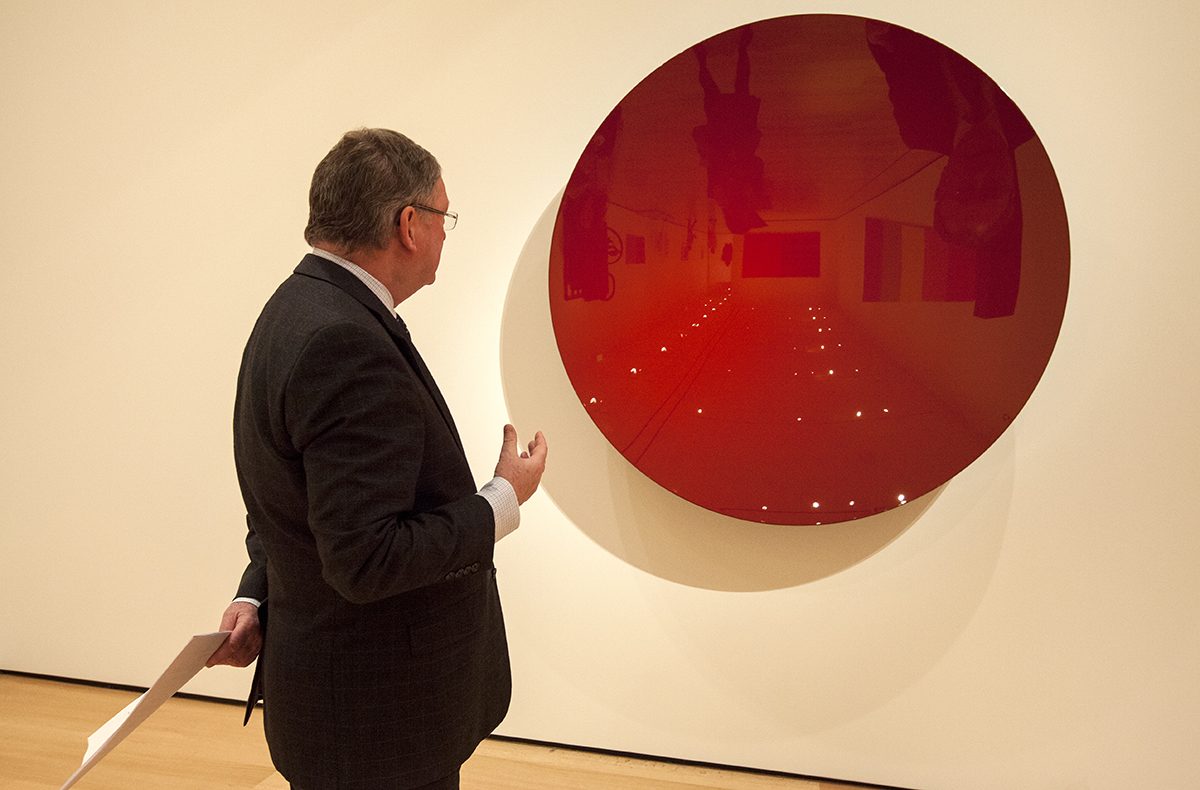

Photo by Olga Khvan

On a Friday morning in April, just as the day’s first visitors made their way into the Museum of Fine Arts, Malcolm Rogers sits on a bench in the Shapiro Family Courtyard, admiring the window washers scaling the glass just behind Chihuly’s Lime Green Icicle Tower. The moment strikes him—even after nearly 20 years serving as the Ann and Graham Gund Director of the MFA—that it’s something he’d never seen at the museum before.

“Every day is different,” says Rogers. “One of the things that I think is critical if you’re director of an institution is not to think that what you did yesterday serves you well the next day. You have to keep moving, keep reinventing.”

During his tenure, Rogers, who announced his plans for retirement two months ago, has overseen a series of reinventions at the MFA, including restoring and reopening its Huntington Avenue and Fenway entrances, eliminating admission fees for children 17 and younger, extending its hours to seven days a week, and instituting a series of community days and cultural events. Each one of these developments is bound by a common goal of making the museum a more accessible place for all.

“I’m very pleased with the way the museum has moved from being a rather enclosed institution to something that’s much more outward-looking and welcoming,” says Rogers. “This feeling of energy and excitement is something that’s been brought into the museum over the last decade.”

But at 65 years old, Rogers is ready to keep reinventing his own life and, as a result of his departure, usher the museum into a new phase as well.

“I could stay here all my life, in a way, but life is a matter of choices,” he says. “In 15 years I’ll be 80, and I think it would be nice to have another phase in my life. I’ve changed the museum here, made many friends here, and so on, but 20 years is a long time to be the dominant influence on one institution. Someone else may bring a different tone, a different theme, different ideas.”

The arts contribute not only to the life of the city and the state, but also to the economy of the city and the state. That is an investment that I believe is necessary.

In terms of personal reinvention, Rogers plans to travel more, not only to discover new places, but also to revisit old ones, seeking to “rebalance” his time spent in his homeland of England and his adopted hometown of Boston.

In terms of reinvention for the museum, which will become the responsibility of his successor, Rogers emphasizes the importance of renovation.

“For me, it’s very important to bring all the galleries throughout the museum up to the standard of the American Wing and the Linde Family Wing,” he says. “We still have galleries that badly need renovating, reinstalling, and we have collections in store that I’d like to bring out into the galleries.”

Additionally, Rogers would like to see the neighboring Forsyth Institute building, purchased by the museum in 2007, transformed into a study and research center for curators and conservators, as well as a repository for reserve collections. But although he has his own visions for its development, Rogers plans to leave the museum entirely in the hands of the next director. (He has “one or two outstanding people around the world” in mind, but claims to play no role in choosing.)

“I think when you leave, you leave,” he says. “What I would not want to do is breathe down the neck or look over the shoulder of my successor. If they want my help or advice, I’m willing to do that, but clearly, none of my predecessors sought to intrude, and I think it’s the polite and correct thing to do.”

In his “last act” at the MFA, Rogers is concentrating on fundraising and marketing efforts to ensure that he leaves the museum on a stable base.

“I put a lot of thought into when was the right time to retire, and once I made my decision—there’s a feeling of relief, I must say, but also a feeling of responsibility because you want to leave things in good shape for your successor.”

To say very publicly, ‘We share your joy’ or ‘We share your sorrow’ is an appropriate thing for the museum to do as a good citizen. … The institution is a citizen of Boston.

In addition to its own fundraising efforts, Rogers hopes for the museum and other art institutions in the area to receive additional support from the city and state—an investment in the arts that is necessary, but has been sparse, he says.

“It is an investment—it’s not an expense. The arts contribute not only to the life of the city and the state, but also to the economy of the city and the state. That is an investment that I believe is necessary and would be repaid many times.”

But for Rogers, the MFA is more than just a contributor to the city’s economy or a place for strictly the arts: it’s also an active member of the city’s community itself, one that sets standards of education and social responsibility, and immediately responds to things that affect the city, whether good or bad.

After the Red Sox won the World Series last year, for example, its iconic “Appeal to the Great Spirit” statue outside of the Huntington Avenue entrance suited up in its own tailored Red Sox jersey. After the marathon bombings—and again during the one-year anniversary of the attack—the museum installed “To Boston With Love” in the Shapiro Family Courtyard, featuring more than 1,700 hand-sewn flags created and sent to Boston in a display of love and support.

“To say very publicly, ‘We share your joy’ or ‘We share your sorrow’ is an appropriate thing for the museum to do as a good citizen,” says Rogers. “The institution is a citizen of Boston.”

Below, follow Malcolm Rogers as he revisits his favorite places and current exhibits at the MFA:

A Tour with MFA Director Malcolm Rogers