MFA Displays Gustav Klimt Painting for First Time Ever

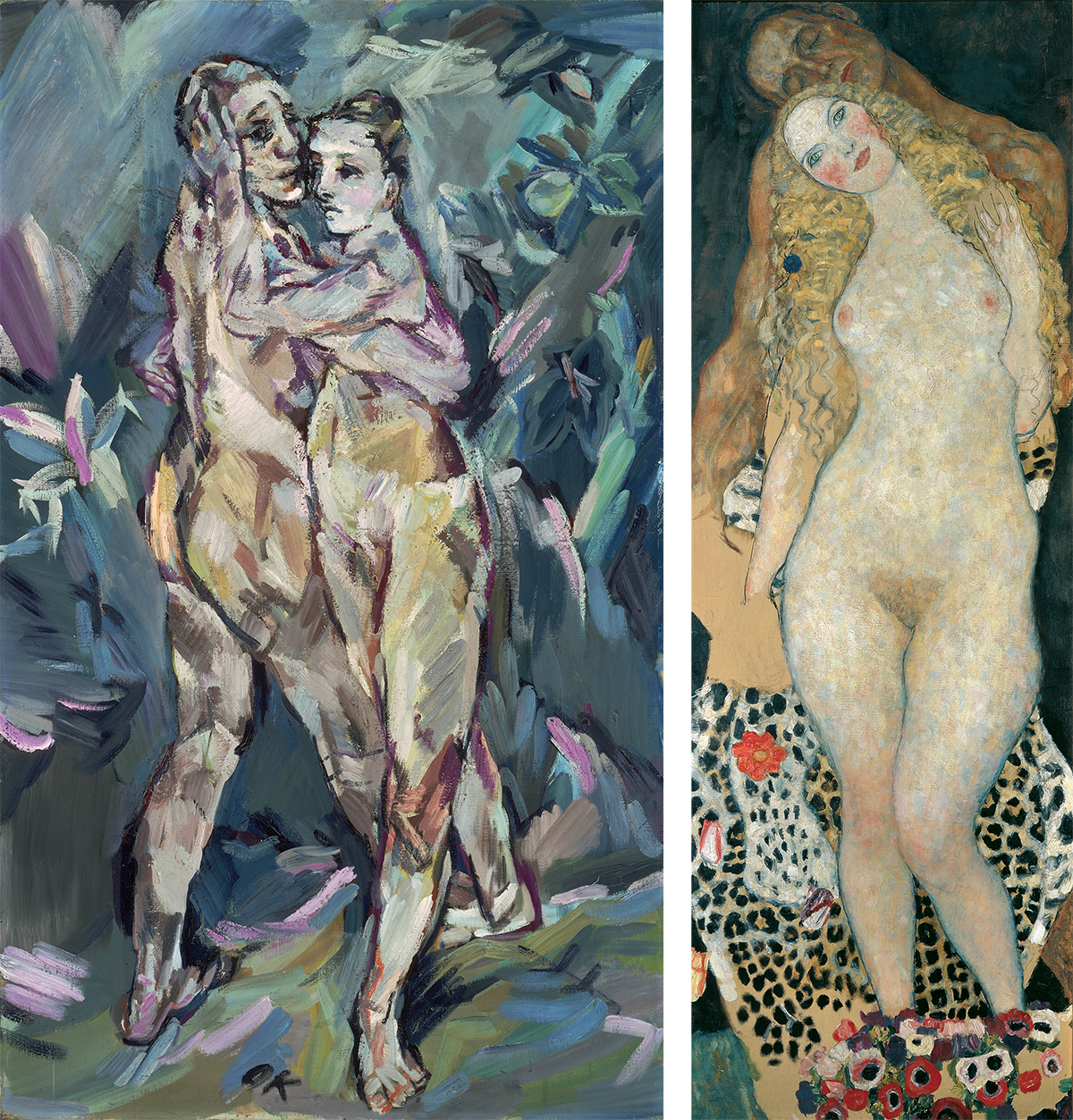

From left, “Two Nudes (Lovers)” by Oskar Kokoschka is juxtaposed with “Adam and Eve” by Gustav Klimt at the MFA. / Images courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts

When the MFA received a request for three of its paintings by Monet to be featured in a major exhibition at the Belvedere Museum in Vienna, Ronni Baer, the MFA’s senior curator of European paintings, knew exactly what she wanted to ask for in return.

The Monets were shipped off to Vienna, and in exchange, “Adam and Eve,” one of the last paintings begun—and left unfinished—by Austrian painter Gustav Klimt before his death in 1918, arrived in Boston.

The Belvedere boasts the largest collection of works by Klimt in the world, including “The Kiss,” an iconic image that shows off the artist’s signature use of gold leaf, which Baer identifies as one of the most prolific works found in college dorm rooms. But the idea of cajoling the Belvedere to send “The Kiss,” the crown jewel of its Klimt collection, to Boston? “We didn’t even try it,” Baer says.

Instead, she brought “Adam and Eve,” perhaps the second most popular of the Belvedere’s Klimt works, in her opinion, to the MFA—and this was far from “settling.” Its installation, the latest presentation of the MFA’s “Visiting Masterpieces” series, marks the first time the museum has ever displayed a painting by Klimt in its history.

Currently, “Adam and Eve” is on view inside the Charlotte F. and Irving W. Rabb Gallery. Many of its visitors have been in the female, college-age demographic, the ones who would have Klimt hanging in their dorm rooms and likely would have found out about the exhibition through Instagram—the MFA’s post about the painting received a higher-than-usual number of likes, noted PR coordinator Isabella Bulkeley.

The painting depicts a fully exposed Eve, “the original femme fatale,” a frequently recurring concept throughout Klimt’s works, Baer says. A sleeping Adam appears behind her, his dark skin a sharp contrast to the mother-of-pearl quality of Eve’s. Her left hand—left unfinished due to Klimt’s death—would have likely held the symbolic apple, though scholars classify the painting as a representation of Eve’s creation from the rib of Adam, not her temptation and decline.

At the MFA, “Adam and Eve” is complemented by two of Klimt’s drawings from the museum’s own collection, as well as works by Egon Schiele, Ferdinand Hodler, and Oskar Kokoschka, his contemporaries in turn-of-the-century Vienna. The juxtaposition of the tension between pattern and figuration in “Adam and Eve” and the bold expressionism in Kokoschka’s “Two Nudes (Lovers),” painted four years earlier, forms the centerpiece of the exhibition. “They’re two different ways to show the same thing,” Baer says.

Both Kokoschka and Hodler were drawn to Klimt, who was nearly 30 years their senior, influenced by his liberal use of nudity and unconventional depictions of the human figure. He was, according to art historian Kirk Varnedoe, “part Francis of Assisi, part Rasputin.”

“I interpret that as meaning that he was preaching the gospel of youth and change in addition to being an unrepentant womanizer, obvious in the overt sensuality of his work,” Baer says.

“Visiting Masterpiece: Gustav Klimt’s ‘Adam and Eve'” is on view at the MFA through April 27. For more information, visit mfa.org.