Revisit the Glamour of the Ocean Liner Era at the Peabody Essex Museum

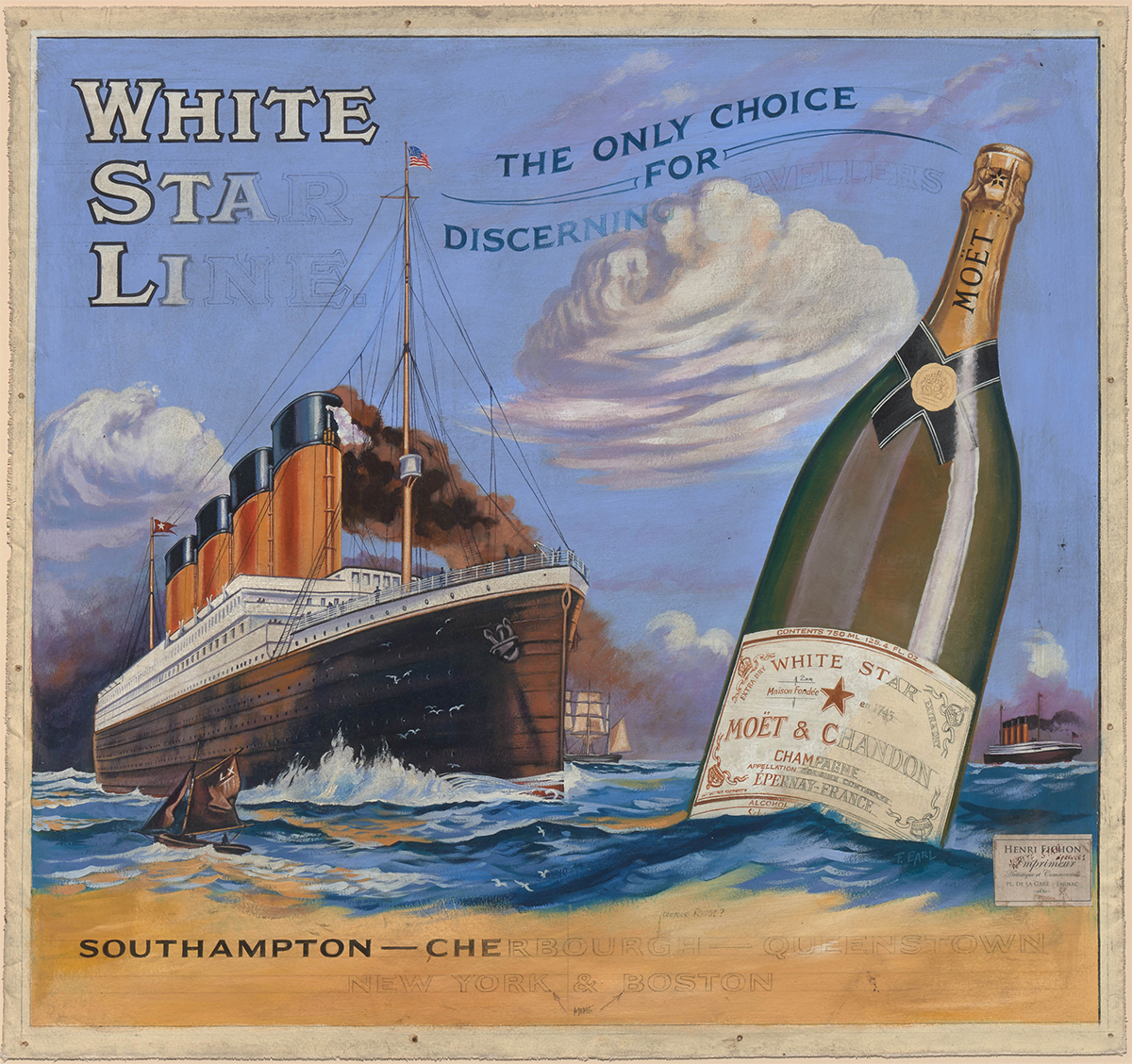

F. Earl Christy, Design for a poster for the White Star Line and Moet & Chandon, about 1912. Oil on canvas. Peabody Essex Museum, Museum purchase, 2014.13.1

If your only awareness of ocean liners is Kate Winslet kicking Leonardo DiCaprio off of that door in Titanic, you’re missing the bigger picture. The massive boats were part of an important era in global travel, one defined by glamour and new technology that made crossing the ocean easier than ever before. The Peabody Essex Museum’s latest exhibit, “Ocean Liners: Glamour, Speed, and Style” seeks to rectify that.

The first ocean liners started making trips all the way back in 1840 and the era didn’t end until the 1960s, says curator Dan Finamore. The PEM’s display offers a glimpse into a bygone era, with pieces of old ships, samples of the art deco-inspired brochures used to promote them, and even scale models of a few ships.

The whole experience offers a glimpse into an era when travel by sea meant a certain sense of prestige.

“Gradually, over the course of time, the shipping companies recognized that the more amenities they offered, the more first-class passengers and better-paying customers they could get, and so they packed their ships with special activity spaces, fancy restaurants, and the glamour associated with an aspirational kind of experience,” Finamore says. “They would design these public areas to look like the fanciest Parisian art deco apartments.”

Passengers were so keen to make the most of their trips that they would reserve deck chairs in advance to solidify their social status. “Where that deck chair was would indicate how knowledgeable you were about ocean travel,” Finamore explains. If your deck chair didn’t have the exact right combination of available sunlight and gentle breeze, you might as well stay home. Plus, angling to reserve one in the right locale would mean you were positioned close to the other VIPs, another strong indicator of status.

Bremen Europe Norddeutscher Lloyd-Bremen “Die Kommenden Grossbauten…”, about 1928. Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum, Gift of Mr. Frederick Reinert, HE945.N6-B7-1928. © Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum. Photo by Allison White

But it wasn’t all hobnobbing. Passengers also enjoyed deck tennis, shuffleboard, swimming, and more. And if you were more interested in spiritual matters, the ocean liners were ready for that, too.

“By the ’20s, and certainly into the ’30s, they were building purpose-built spaces for Catholic mass, and then by the late ’30s they were building purpose-built synagogues on board ships for Jewish services as well,” Finamore says. Don’t want to leave your pup behind? There were kennels. Worried about learning how to drive a car in Europe? Bring your car with you.

The exhibit also steers into the stories of the rich and famous who journeyed on the ships. There’s a Cartier tiara worn by Lady Allen, which she wore the night the Lusitania sank. She didn’t save the tiara herself, though—in a moment of incredible employee loyalty, her maid, who was in a separate boat, rescued it herself. There’s even a broach that Richard Burton gave to Liz Taylor after The Night of the Iguana was released. Taylor was photographed wearing it while coming off of the Queen Elizabeth.

But Titanic fans will find plenty to marvel at as well. “We have some very good material related to the Titanic, to the Lusitania, and to the Andrea Doria, three of the most famous ocean liner disasters,” says Finamore, including a Titanic handbill “that advertises that passage of the return voyage, the first west to east voyage, which of course never happened.”

While Titanic was aiming for New York, there were, briefly, ships that came in to Boston as well, but it didn’t last long. In fact, Samuel Cunard, of the Cunard Line, initially wanted Boston to be his line’s terminus. “Unfortunately, in 1844, there was a very cold winter. Boston Harbor froze over and they couldn’t get in or out,” Finamore explains.

“The various commercial entities tried to satisfy the Cunard company by chopping a two-mile-long channel through Boston Harbor ice so ships could get in and out, and it worked, but Cunard still wasn’t convinced that Boston was the place to be.” Shortly thereafter, he moved the line to New York.

Hard to blame him.

May 20-October 9, Peabody Essex Museum, 161 Essex St., Salem, pem.org.