What Does It Take to Become a Historical Reenactor in Boston?

The contrast between ye olde and the new is utterly, quirkily Boston. But what does it take to become one of these historical interpreters?

Welcome to “One Last Question,” a series where contributing editor Matthew Reed Baker tackles your most Bostonian conundrums. Have a question? Email him at onelastquestion@bostonmagazine.com.

Photos by Jvphoto/Alamy Stock Photo (Hat); Spxchrome/Getty Images

Question:

I grew up going to Old Sturbridge Village, and for years I’ve seen people in historical dress running around with tourists all over downtown Boston. Who are these people, and what does it take to become one of them? —M.S., Roslindale

Answer:

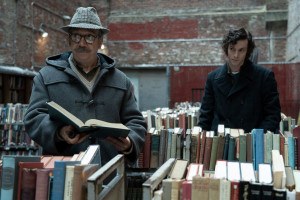

I myself have long been bemused by today’s bewigged and befrocked, M.S., having been raised on “living history” museums all over New England and witnessing many a Colonial dame or dude sauntering by as I grab a cannoli in the North End or a beer in Quincy Market. This contrast between ye olde and the new is utterly, quirkily Boston, and I’ve always wondered how these “interpreters” pull off their historical guises so gracefully and consistently.

To learn more about them, I spoke to two of the leading experts in the state: Richard Pickering, deputy executive director and chief historian at Plimoth Patuxet Museums, and Old Sturbridge Village historian and curator Tom Kelleher. Both agree that most interpreters are outgoing, with an interest in history and maybe even a theater background. Some join up to learn an old craft, while others are former schoolteachers who still love to educate. Intriguingly, Pickering says experience working in retail helps, as store clerks are used to answering the same questions relentlessly with expertise and bonhomie. Plimoth Patuxet, he notes, has another type of interpreter: Indigenous people from the likes of the Wampanoag, Micmac, Abenaki, Massachusett, and Narragansett tribes who are eager to show that their cultures aren’t just a part of the past—they’re complex and alive.

Like life itself, being a part of living history is an ongoing education for these interpreters, who undergo weeks of training and attend countless conferences and workshops. Because Plimoth Patuxet’s English village features a number of “first-person” interpreters who stay in character, each actor gets an extensive dossier on the historical figure they play, as well as vocal coaching in one of the 17 regional dialects spoken there. Meanwhile, their Old Sturbridge Village counterparts have some 41,000 research volumes at their fingertips. And bear in mind that they’re doing most of this on weekends and holidays—Kelleher once held a job fair on Super Bowl Sunday to weed out the Patriots fans from the promising patriotic reenactors. So the next time you see one of these hardworking folks in the village or along Congress Street, be sure to shout “Huzzah!” in your best Worcestershire (not Worcester) accent.