Did a Boston Art Collector Find a Lost Rembrandt?

Cliff Schorer sure thinks so—and the dogged art detective won’t rest until he proves it.

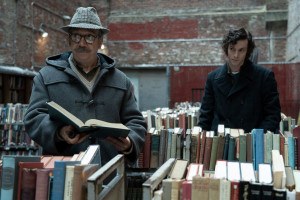

Cliff Shorer discovered a small head study at an auction house in Maryland that he believes is a lost Rembrandt not seen since 1935. / Photo by Matt Kalinowski

In September 2021, art collector Cliff Schorer slipped on a pair of white gloves to inspect rare photographs in a highly controlled room at the Getty Institute library in Los Angeles. He was on a quest to establish the provenance of a drawing purchased a few years earlier at a yard sale in Concord for $30 that Schorer had discovered was, in reality, the work of famed German Old Master Albrecht Dürer—and worth tens of millions of dollars. It was what many in the art world would call a once-in-a-lifetime find. And yet, that very day, it was about to happen again.

Schorer had spent the past several hours poring over documents, examining photos, and taking extensive notes. An infusion of caffeine was in order. He emerged from the archives into the bright Los Angeles sunlight, slid behind the wheel of his rental car, and drove to a nearby café for a cool drink. As he tried to unwind, sipping his iced mocha, a message with a photo popped up in the WhatsApp group chat he shares with the so-called runners throughout Europe and the United States that he pays to sift through the online listings for some of the tens of thousands of pieces of art that go up for auction around the world on any given day. They are on the lookout for potential works of Old Masters—European artists working anywhere between 1300 and 1800—that Schorer and the London gallery he co-owns might like to buy.

Schorer clicked the thumbnail photo on his phone and saw a painting of an older man with a bulbous, red nose; a droopy eye; and a shaggy beard that started under his chin. The message from his U.K. runner said that the painting was up for auction in Maryland, consigned by a church, and listed as “manner of Rembrandt,” meaning it was being billed as created by an imitator of the famed Dutch Old Master Rembrandt van Rijn.

Schorer wasn’t hopeful that it was anything special. “The gin nose is great. Likely a copy,” he typed back on his phone. But as often happens, Schorer’s curiosity got the best of him. He went onto the website of the auction house to get a better look at the painting. It was a small oil sketch, a head study, just 6 by 7 inches, and painted on a wood panel rather than canvas. It looked vaguely familiar, so Schorer pulled up the catalogue raisonné of Rembrandt’s work by scholar Abraham Bredius. Published in 1935, it listed and numbered all the works that were attributed to the master and, for decades, served as something of an official Rembrandt bible. Schorer scrolled quickly to the 200 range, where he knew some head studies had been cataloged. And there it was.

He went back to his phone. “It is Bredius 262, last seen in 1935,” Schorer typed to his runner. Schorer felt certain that the paintings were the same but also knew the one for sale could be a copy, not the original. This, after all, was not his first lap around the art world. An experienced collector and a self-taught Old Master researcher who also co-owns Agnews Gallery in London, Schorer knew full well what he was up against. Rembrandt was not just a masterful painter but also the teacher of a dizzying number of students. His method involved having them paint copies of his paintings, even his self-portraits. As a result, today there are copies of Rembrandt’s work circulating all over the globe, not to mention copies of those copies. Discovering an original Rembrandt is the white whale of art collecting—everyone dreams of finding one, and almost no one ever does.

Schorer, though, revels in the thrill of the hunt. With his phone in hand, he raced back to the Getty Research Institute, bypassed the highly controlled room where he had been researching Dürer documents that morning, and dove into the stacks, pulling books and catalogs on Rembrandt off the shelves. He splayed them out on a table and reviewed the three pictures known to exist of this particular head study that were taken before it vanished into the ether. Then he compared those images against the image of the piece up for auction. It looked like the same painting. Poring over the literature only confirmed Schorer’s suspicions: He could find no documented evidence that a copy of this particular head study ever existed.

Three hours after first seeing the thumbnail photo, Schorer texted back his runner. “Doubt it is a copy…I’m on it.” He asked the runner to request a high-resolution photo from the auction house, urging him to use the utmost discretion. “We need to run silent and deep,” he wrote. Schorer didn’t want anyone tipping his hand. The auction house—not Christie’s or Sotheby’s but rather a small outfit in Rockville, Maryland—didn’t seem to know that they had a possible Rembrandt on their hands. After all, they had estimated its value at $1,000 to $1,500. If it were a Rembrandt, it could be worth $10 million or more.

Schorer immediately began researching the painting’s provenance. The first bit of information he found was in a 1935 catalogue raisonné that listed the painting as being part of a private collection belonging to Josef Block. That was bad news. Schorer knew that Block was a prominent German Jew and well-known artist. The Nazis had spared him the death camps but stolen his art and his home. Schorer also knew that Block’s grandson had worked tirelessly for the restitution of his grandfather’s artwork. This painting hadn’t been seen since 1935 and may have just turned up in a suburb of Washington, DC. Schorer did the math: That small head study was likely Nazi loot that had never resurfaced until now. It happened all the time. The other bad news Schorer already knew was that after having considered the head study to be a true Rembrandt for centuries, a prominent art historian who wrote the 1968 catalogue raisonné had deemed it not to be deserving of Rembrandt attribution, but likely made by an imitator—even though he never saw it. Schorer believed that decision was a mistake.

A dogged and skilled researcher, Schorer knew first-hand that proving the painting was a true Rembrandt would take more time than he had. The auction was only five days away. It would also take him much longer than that to determine whether the Nazis had stolen the painting from Block. Even if he bought the painting and could convince Rembrandt scholars to reintroduce it into Rembrandt’s corpus, he would still end up having to return it to Block’s heirs if he learned it had been looted. Staring at the painted image of the old man with a slightly lost look on his face, Schorer knew what he had to do. He wasn’t going to let his chance at a Rembrandt slip through his fingers.

Discovering an original Rembrandt is the white whale of art collecting—everyone dreams of finding one, and almost no one ever does.

The next day, just as the sun was slipping behind the horizon, Schorer’s transcontinental flight made its final approach into Logan airport. When he landed, an email from his U.K. runner arrived in his inbox with the high-resolution photo from the auction house. Schorer opened it and zoomed in to inspect the painting—the brushstrokes, the use of paint. As he looked, he noticed a horizontal crack in the panel, about an inch from the bottom, that ran along the grain of the wood and appeared to have been filled in with glue. He immediately opened the 1906 black-and-white photo of the lost painting, which was the highest-quality shot that existed. There, he saw it: a crack in the wood panel, about an inch from the bottom, along the grain of the wood.

Jackpot.

Schorer’s lingering doubts from the night before were suddenly a distant memory. He was convinced this was the lost Rembrandt. He also knew from experience that he would need to see the painting himself. The next day, he went right back to Logan and boarded a flight to DC.

Back on the ground, Schorer drove his rental car to the auction house, which was tucked away in a nondescript corporate office park, and walked inside. “Has anyone else been in to preview the lots for Friday’s auction?” he asked the woman attending him. She said they had but wouldn’t say how many. Schorer looked at the long wall of art and stared at the small head study. Two other customers came into the room, so he began looking at other paintings in a long-practiced, subtle act of subterfuge.

When Schorer finally reached the painting that he was there to see, the first thing he did was inspect the back of it. The Nazis were highly efficient at recording and identifying everything they stole from the people they sent off to be killed. The painting didn’t bear a Nazi stamp on it. That didn’t mean anything definitive, but it offered some encouragement.

As he flipped the painting to the front, holding it by its ornate wooden frame, Schorer noticed the economy of the paint used to render the face, the masterful strokes. Then he got that familiar feeling: the hairs on his arms standing on end and the rushing in his chest. He calls it the “first blush of love” and the feeling he “lives for.”

Schorer has made the pursuit of this sensation his life’s work, constantly crisscrossing the globe, hardly ever in the same place for more than a week, chasing after one piece of artwork or another. He’s likely the closest thing to James Bond that the art world has to offer. For more than three-plus decades, the 56-year-old has bought and sold a large number of gorgeous and important pieces. Sometimes—remarkably often considering how rare it is—he comes across a major find that has been overlooked. Once, years ago, he discovered a Guercino self-portrait at a tiny sale in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. It now hangs in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Another time, just this past year, he found a Cornelis van Haarlem at a sale in New Jersey and sold it for an undisclosed amount to the Art Institute of Chicago.

Perhaps the most surprising detail about Schorer’s life, though, is that he’s become such a remarkably successful art hunter without an advanced degree or any formal art history education. In fact, he never even graduated from high school.

Cliff Schorer, pictured at the Worcester Art Museum. / Photo by Matt Kalinowski

Growing up on Long Island, Schorer was obsessed with history and collected stamps and coins. He detested school. The bright but rebellious son of a prominent businessman and Columbia Business School professor, he was also very into computers. At nine years old, right around the time his teacher sent a note home telling his parents she thought their son was beyond hope, Schorer was tinkering with computers in his garage. At 13, he had written a computer program used by the New York Board of Regents. (They never met him in person.) At 15, he dropped out of high school.

When he was 16, in 1982, Schorer moved to Boston to try his hand at college, specifically an independent study program at Boston University for non-traditional students like himself. He quit six months later after leaving his age off a job application and landing a position as a computer programmer for Gillette. He was fired after his father ratted him out, revealing Schorer’s age to management. Instead of going back to college, as his father wished, he started his own company dedicated to corporate acquisitions and the sale of computer equipment. He was 17 years old.

Schorer was making good money when the old collecting bug he’d had as a child kicked back into gear. He spent the next three years scoping out auctions, buying and selling some 300 pieces of Chinese export porcelain. In his early 20s, he became interested in—or you could say obsessed with—Old Master paintings and started reading historical and current sales catalogs from auction houses on his quest to understand the marketplace. Then he taught himself everything he could about the Old Master painters he loved, initially focusing on the Italian Baroque era. He passed countless hours at the Boston Public Library until he exhausted what it had to offer. Granted access to Harvard’s Fine Arts Library, he spent every night of the week there reading books and documents that filled hundreds of feet of shelves.

Armed with a solid knowledge base, Schorer felt ready to hit the auction houses. For the first few years, he bought art in the $10,000 to $30,000 range. By the time he was 28, he was buying pieces in the $100,000 to $500,000 range. His appetite for collecting at such a young age garnered attention at Christie’s and Sotheby’s, and the houses began taking an interest in him. Before long, he was mingling in the rarified world of prominent art collectors.

For a long time, it was just a hobby, even if it was one that made Schorer money. His day job, the source of his wealth, was a business he owned that bought companies in bankruptcy and then sold them off one piece at a time, from the intellectual property to the office furniture. For Schorer, art and business remained separate.

Schorer’s first leap from art collecting to the business of art (albeit at a nonprofit) came some 20 years ago, when Jim Welu, then the director of the Worcester Art Museum, asked him to get involved with the museum as a corporator. Schorer, who had a great admiration for the museum’s impressive collection, accepted and, in 2006, was named to the board and became the museum’s board president in 2011.

The museum also got something less expected out of Schorer: his art-detective skills. Recently, Schorer has been working to crack a cold case from 1978 in which 12 paintings were stolen in a brazen heist from the home of a former museum trustee. Three of the paintings had already been found before Schorer came on the scene, and two of those had been linked to the same art dealer from western Massachusetts. The other nine—an estimated 10 million dollars worth of art—are still missing.

It wasn’t until 2013, though, that Schorer really wed art to business. He caught wind of a rumor that London’s venerable Agnews Gallery was considering liquidation. Schorer desperately wanted to buy its art library, but after he began discussions with the owners, it became clear that it made more sense to buy the gallery itself. The only way Schorer would do that, though, was if he had the partner of his choice: Lord Anthony Crichton-Stuart, the former head of Old Master paintings at Christie’s, who Schorer had known for years. Schorer, who loves flying under the public’s radar, asked Crichton-Stuart to oversee the art and serve as the gallery’s public face. In exchange, Schorer would handle the business side while continuing to hunt for art. Crichton-Stuart agreed. In the end, Schorer became the lead investor and purchased the entire business. Since then, Schorer has been sure to tell Crichton-Stuart whenever he thinks he’s discovered a painting of note.

When Schorer told his partner that he’d likely found a lost Rembrandt, they both knew that the journey ahead was long and that the outcome was far from guaranteed. Schorer followed up his text with another message, this one containing only a single photo of a self-portrait of Rembrandt laughing. The implied message was clear: Either Schorer had found the great white whale itself, an actual Rembrandt original, or the Old Master himself was laughing at their folly.

The face in the painting appears to be the head study for King Saul, the famous Rembrandt above. / Städel Museum, Frankfurt Am Main

At 10 minutes before 10 a.m. on September 24, 2021, Schorer pulled his silver Prius off I-84 and into the parking lot of a diner in Vernon, Connecticut. He was on his way to Manhattan to see a Medici portrait exhibit and had an appointment to tour it with the show’s curator. But first, he needed to win the Rembrandt at auction in Maryland.

Schorer had registered to bid by phone and was waiting for the auction house to call him. As he waited in the car, he pulled his laptop out of his briefcase, connected to his hot spot, and logged into two auction platforms that he regularly uses so he could watch the bidding unfold online while he was on his cell with the auction house. As the clock neared 10, he found it odd that no one had called. He felt his stomach tie up in knots. The painting was the second lot on the auction block that day. It would come up within a minute.

When his clock struck 10 and his phone still hadn’t rung, Schorer panicked, grabbed his cell, and called the auction house. No answer. He dialed again. Still nothing. He looked online. One platform showed bidding at $2,000, the other had it at more than $37,000. What was going on? He kept dialing frantically over and over. Sitting in the warm September sun inside his tiny Prius, the panic in his chest was growing by the second as he considered the possibility that he was going to miss the auction and lose his shot at the painting.

Finally, there was a voice on the other end of the line. “I was waiting for a call to bid on lot 2,” he said. “Hold on, hon. We are having a problem,” the woman replied. He stayed on the phone until they transferred him to someone who would relay his bids. Schorer breathed a sigh of relief that he hadn’t lost the painting. At least, not yet.

By the time he was squared away and ready to go, the bidding for the painting was at $37,500. That meant Schorer wasn’t the only one who thought this was a lost Rembrandt. He had knowledgeable competition. “Open at $50,000,” he told his phone bidder.

A competitor bid $60,000. Schorer bid $70,000. Someone else bid $80,000. And on it went as Schorer dueled it out in ten-thousand-dollar increments with two other bidders.

When the sale price reached $150,000, one of Schorer’s opponents bowed out. Now he was just one-on-one with a single competitor. Schorer had no idea who the person was, how deep their pockets were, or how high his opponent was willing to go. An auction usually takes a minute per lot, and they were nearing the five-minute mark. It was starting to feel like an eternity.

As the price neared $200,000, the auctioneer downshifted to $5,000 increments. When the price rose to $220,000, the auctioneer called out $225,000. “Would you go that high?” the phone bidder asked Schorer. He confirmed he would.

“I have $225,000; I’m looking for $230,000,” Schorer remembers the auctioneer saying. There was silence. “Do I have $230,000?” he called out again. Nothing. “Going once, going twice, sold,” he said. Schorer heard the hammer. It was finally over. The painting was his.

The moment after Schorer hung up the phone, it rang again. “Vas that you, Clifford?” a voice in a thick German accent said on the other end of the line. It was the competitor who Schorer had vanquished in the bidding: an Old Master scholar and a friend. Theirs was a very small world. Schorer now knew who he had been bidding against. And they both knew—or at least thought they did—what Schorer had just bought.

Schorer was elated, but then another feeling washed over him: dread. He faced enormous obstacles, and it could take years of research to overcome them. Schorer was convinced the painting he’d just spent $288,000 on (with the so-called buyer’s premium paid to the auction house) was the original painting last seen in 1935. But now he had to get it reintroduced into Rembrandt’s oeuvre. If he couldn’t prove it was a true Rembrandt, it would be worth much less. Maybe even less than what he had paid for it.

For many years, for better or worse, anyone who suspected they had a Rembrandt went to one man to find out if they were right: Ernst van de Wetering, the Dutch art historian widely regarded as the ultimate arbiter of whether a painting deserved a Rembrandt attribution, and a member of the Rembrandt Research Project. But he had died several weeks before Schorer bought the painting. Now there was no longer a single gatekeeper to the attribution kingdom but a field of highly regarded experts in the United States and Europe. Schorer was determined to visit as many of them as possible and hopefully reach a consensus that this painting should be back in Rembrandt’s oeuvre.

To do this, Schorer knew the road ahead: He’d need to log thousands of miles in his aging 2012 Prius, carting the painting around the United States, and board several transatlantic flights to fly it to different points in Europe. He’d also need to submit the painting to a battery of cutting-edge scientific tests and scans to date the wood and the paint and to see if there was anything beneath the painting. It was no small task, requiring time and lots of money.

As Schorer pulled back onto I-84 heading southwest toward the Medici show in New York, he played the movie forward in his head to what he feared was its final scene: Schorer standing at a ceremony handing over the painting to Josef Block’s heirs after he found out it had, in fact, been stolen by Nazis. Schorer knew he would do the right thing, he was sure of it, but also knew it meant handing over a painting for which he had just paid more than $250,000—and that could be worth 40 times that.

Schorer is the closest thing to James Bond that the art world has to offer. / Photo by Matt Kalinowski

A couple of days after the auction, Schorer was at his Provincetown home—a glass-walled modern beauty designed by famed architect Walter Gropius and members of his studio—when his phone rang. On the other end was a woman from the Maryland auction house, who reported that she had just received the strangest call from a European art dealer.

Schorer tensed up immediately. “Let me guess,” he said. “He told you that you just accidentally sold a Rembrandt and that you should renege on the sale and sell it to him for a great deal more, right?” She told him he was correct and that the house would do no such thing but had just wanted to alert him. Then Schorer shared some information with her. “I have a pretty sure indication that this painting could be war spoliation,” he said, adding that if his research concluded that it had been stolen by the Nazis or anyone else, he would return it to the family who owned it. This wasn’t his first rodeo, he assured her; he’d previously restituted paintings that he later learned through his own research had been stolen. He was prepared to do it again. “You cannot be sure that others would do the same,” he told her.

The vultures were circling. Since the auction, the news of a tiny painting that had sold for more than 200 times its $1,000 estimate in Maryland had run in an auction newsletter and a well-known art-history blog. Scholars and collectors around the world were buzzing about the piece and that someone—very few people knew who—had bet big that it was a Rembrandt.

After Schorer hung up the phone, he wired the auction house the money for the painting, threw a few things in a suitcase, and pointed his Prius toward Maryland. Schorer knew the auction house wouldn’t sell to the dealer who called, but what if someone else showed up with a ruse, claiming to be a distant relative of Josef Block and demanding the painting? Schorer had been in this business long enough to know that he couldn’t underestimate the lengths to which some people would go to get their hands on a Rembrandt.

The next day, Schorer picked up the painting—packaged between two pieces of cardboard and placed in an elegant paper shopping bag—and battled rush-hour traffic into DC. He pulled onto a tree-lined street in the Cleveland Park neighborhood and rang the bell of an old wood-frame home. Arthur Wheelock, an Uxbridge native who is an esteemed Rembrandt scholar and the recently retired curator of northern Baroque art for the National Gallery of Art, answered the door and welcomed his old friend.

Wheelock had known Schorer for 15 years and was always impressed with his knowledge, passion, and determination to “leave no stone unturned” when researching art. He was happy to look at the painting before they headed out to dinner together. They walked into his small garden out back and sat at a wrought-iron table, where Schorer carefully unwrapped the painting. Wheelock looked at it in the early-autumn afternoon sunlight. “The brushwork is looser than I am used to seeing,” Wheelock said. “I think of Rembrandt’s heads as being more structured.” Wheelock didn’t say so out loud, but he was skeptical.

Meanwhile, at around the same time, some 4,000 miles away in Frankfurt, Germany, Stephanie Dickey—a Fall River native and a professor of art history at Queen’s University in Canada—was strolling across the shiny floors of a grand gallery at the Städel Museum. The Rembrandt show Dickey co-curated was in the midst of being put on display. Along the gallery’s walls, some of the paintings were already up, and others were being ferried to their designated spots, each marked by a large brown paper rectangle with a photo of the painting taped to it for reference. When Dickey got to the painting David Playing the Harp Before Saul, she stopped to admire how it looked in its dark black frame against the soothing blue-gray wall. Then she felt her heart skip a beat as she suddenly saw something she had never seen before.

Dickey had stared at the painting countless times, but now it was clear as day: The face of Saul, underneath a twisted turban, had a bulbous nose, a droopy eye, and a beard that started underneath his chin. It was nearly identical to the face in that small painting recently sold in Maryland that she had noticed on an auction platform days before the sale and that everyone in her Dutch-art-focused corner of the universe had been buzzing about ever since. Somehow, no scholar had ever made the connection: Schorer’s painting of the old man appeared to be the head study Rembrandt used for Saul.

Back on the other side of the Atlantic, the day after Schorer had visited Wheelock with the painting, Wheelock was sitting at his computer when he received an email from Dickey. She wanted to know if Wheelock might know who had bought the painting recently sold in Maryland, because it looked like it might be the head study for Saul, and she wanted to examine it. Wheelock immediately rose from his desk, walked over to his bookcase, and pulled a Rembrandt book off the shelf. He flipped through the pages until he found the painting. He leaned in to carefully inspect the face of King Saul. It looked just like the man in the painting he’d inspected in his garden the day before. It even had the same loose brush strokes and unstructured head that, to Wheelock, hadn’t looked as typical of Rembrandt’s work during that era. Wheelock was starting to think that Schorer was right after all.

Schorer’s painting of the old man appeared to be the head study Rembrandt used for Saul.

A few weeks later, in the waning days of October, Schorer boarded a flight to Sacramento, made his way in his rental car to the low-slung building that houses the Center for Sacramento History, and descended into the basement. He had placed an order for probate documents housed there that he hoped would help him fill in a decades-long gap in the painting’s journey from Nazi-era Europe to an auction house in Maryland and ultimately answer the question of whether the painting he now owned had been stolen.

In the few frantic days between when he first learned about the painting and the auction, Schorer had gotten his first clue: a plaque on the painting’s frame that said, “To the Fathers, Affectionately, Nina & Clark Hartwell.” He managed to determine that Clark Hartwell was somehow involved with the invention of Velcro and, before that, was a famous aerospace engineer during World War II. Both he and his wife were dead. Schorer tracked down their children and called them, but they declined to talk to him. He had hit a dead end.

Schorer soon tried another approach. In the 1968 catalogue raisonné of Rembrandt, the author noted that the piece—which he deemed not to be a Rembrandt—had been sold at the Parke-Bernet auction house in New York in 1947. Schorer learned that the auction house no longer existed but that Sotheby’s had bought it in 1964. He dialed a deep contact he had within the research department of Sotheby’s and asked if the researcher could do him a favor: look in their archives for the line card from that auction. Soon after, Schorer’s source sent him a photo of the entry from the card catalog that indicated the piece, a Rembrandt, had been consigned by “Trivas” and purchased for $2,500.

Trivas was a familiar name. Schorer figured it had to be the art historian and Frans Hals expert Numa Trivas. He did some research and found that Trivas had served as the curator of the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento. The question was, how did Trivas get the painting? And more to the point, how on earth did Trivas sell it in 1947 if he was already dead by then?

Schorer hoped the answers to those questions lay in that Sacramento archive basement. He gave the archivist his name and order number and waited for her to return with a stack of papers from probate court on Trivas’s estate. She showed up with several inches of photocopies, and Schorer wrote a check for $196 to take them home. On the flight back to Boston, Schorer settled into his economy-class seat—he always books economy—with his reading material and dug in, taking detailed, handwritten notes along the way.

He learned that Trivas was Jewish and had fled Germany to Holland. From there, he caught the last boat to America before the Nazi invasion. On the steamer with him sailing west was a crate filled with some 30 paintings. He was smuggling them to America, but not to sell them. They belonged to Jews. He was ferrying them to safety.

Just a few years after arriving on the shores of America, Trivas died. But he’d left behind extraordinarily detailed notes about the owner of each artwork, including when it could be sold and how much his estate would get for commission. He listed family members and heirs should the paintings’ owners not survive the camps.

Schorer was at cruising altitude somewhere over the Midwest when he spotted what he’d been looking for: the instructions for what to do with the Rembrandt head study. It was only to be sold after the Nazis were no longer in power. The proceeds, minus his own commission, were to go to a woman named Anna Louise Jones, Block’s daughter. Since Trivas died before the Nazis were out of power, his estate’s executor sold the painting to an intermediary, who sold it to the Hartwells. The funds, minus his commission, went to Jones. Schorer could hardly believe his eyes—or his luck. The painting was not stolen but smuggled by a one-man underground art railroad from the advancing march of the Nazis to the safety of America, where its owner had sold it.

In the weeks that followed, Schorer called the upstate New York monastery that had put the head study up for auction in Maryland to find out how they had come to own the piece. He learned escaping the Nazis wasn’t the only close call for that little painting.

A father there told Schorer that the head study was a gift from the Hartwells to the priests at their church. For years, it hung on a wall near the fireplace in a monastery and retreat center on a ridge high above the Pacific Ocean in Montecito. Then one night in 2008, the monks were sitting down to dinner while the Tea Fire burned below the ridge line. As the flames grew more voracious, they realized they were in danger and decided to flee. Once they had all evacuated, one of the monks went back into the monastery at the last minute, grabbed the head study off the wall, and whisked it away to safety. Soon after, the monastery and everything left inside burned to the ground. The rescued painting was sent to the monastery in New York.

About a month after his breakthrough on the painting’s provenance, Schorer received more good news in an email he’d been anxiously awaiting from Dr. Peter Klein. A little more than a month earlier, Schorer had taken a very high-resolution scan of the edges of the painting’s wood panel and sent the image to Klein, a German expert in wood identification who specializes in dating wood used in artwork through what is known as dendrochronology. When Schorer opened the email with the report, the analysis said the painting could have been made any time from 1619 onward. That was positive because it meant the painting had been produced very early in Rembrandt’s career when he didn’t have students who could copy him.

Schorer was pleased. Then he kept reading the dry, technical language, which communicated something thrilling. The wood panel upon which the head study was painted came from the very same tree as another Rembrandt painting. In fact, the grain patterns were so similar it appeared they came from the very same board.

The deeper Schorer dug, the more he discovered. He soon realized that many of the old men depicted by Rembrandt looked just like the model in the head study. It started to seem as though the piece had served as a type of central casting; when Rembrandt needed an older man, he pulled out that study and used it in his paintings. Schorer also learned that the paint used in his piece was the same paint used on other Rembrandts.

Still, none of this is enough to definitively prove that the head study was painted by Rembrandt and not by someone painting in his workshop alongside him. That’s where connoisseurship becomes important. And Schorer has made progress there, too. Wheelock says he is growing more convinced the painting is a Rembrandt. So is Otto Naumann, another Rembrandt specialist considered by some to be the top authority in the world. Dickey finally saw the head study that she connected to Saul and says Schorer’s case for attribution is “looking good.” Gary Schwartz, another esteemed Rembrandt scholar in Holland, says that Schorer’s attribution of the painting to Rembrandt is “not only convincing, it is thrilling.”

In January, Schorer will treat scholars to an unveiling of the painting at a gallery on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. Abstracts of academic papers based on the painting will be presented, and, after the event, Schorer will publish a book of their studies and his research in hopes that his little painting will once again be back in Rembrandt’s oeuvre—and command the price of a Rembrandt, too.

By the time Schorer and his gallery decide to sell it, Schorer undoubtedly will have moved on to other projects. Perhaps he will have recovered the winter scene by Dutch Old Master Hendrick Avercamp—one of the nine still-missing paintings from the art heist in Worcester that he has been investigating. After all, he says he already knows where it is. Or perhaps he will be in hot pursuit of yet another once-in-a-lifetime find. Since buying the possible Rembrandt, he says, he’s found a Middle-Kingdom Egyptian priestess of Isis sculpture at a Buffalo auction house, and a museum has already requested to exhibit it on loan. And then there’s a piece he’s found that he will only describe as a “major Italian Baroque painting.”

And on he will go until the day he finds the ultimate painting, perhaps a Da Vinci, that he would sell everything he owns—all of his paintings, his gorgeous Gropius house, his homes in Boston, New York, and London, and his business—to possess. “The end goal,” Schorer says, “is to die in a cardboard box with one truly great masterpiece.”

First published in the print edition of the December 2022 issue, with the headline “Searching for Rembrandt.”