How an $18 Throw Pillow Helped Locate a Famously Stolen Painting

Boston art hunter Cliff Schorer used metadata and some good old-fashioned shoe leather to track down—hopefully!—a filched painting by Dutch master Hendrick Avercamp.

Many of the most valuable paintings stolen from the Stoddard family in the 1978 heist were intended gifts to the Worcester Museum of Art, pictured above. / Courtesy of Worcester Art Museum

One morning in 1978, Robert Stoddard, a prominent Worcester businessman, and a former trustee of the Worcester Art Museum, emerged from the master bedroom of his stately home and noticed a fire poker leaning on the wall just outside the bedroom door. He hadn’t put it there. So who had?

Stoddard scrambled downstairs into his living room. Above the fireplace, where his wife’s beloved landscape painting by the Impressionist master once hung, was a blank spot. He looked around the room. The Turner large-format watercolor was gone. The Renoir was missing. The Hendrick Avercamp had vanished. And on it went, no matter where he cast his gaze. In all, someone had stolen 12 pieces of artwork—worth some $10 million today—from Stoddard’s house while he slept peacefully upstairs.

Nearly half a century later, only three of those artworks have been recovered. Then the trail went cold. Until, that is, last year, when art collector Cliff Schorer started looking for the missing paintings. If all goes according to plan, in January, he is poised to recover one of the most valuable stolen pieces: “Winter Landscape with Skater and Other Figures” by 17th-century Dutch master Hendrick Avercamp.

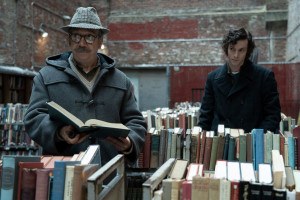

Schorer, who owns homes in Boston and Provincetown, is a noted collector and has made a name for himself as an art hunter with an uncanny knack for finding—and acquiring for cut-rate prices—lost, overlooked, or misattributed masterpieces worth millions. Now, he is training his sleuthing skills and deep art-world connections on recovering the artworks stolen from the now-deceased Robert Stoddard. The mission is personal: He is the former board president of the Worcester Art Museum, and several of the stolen pieces were promised gifts to the museum.

Last year, Schorer began where anyone might: On the Internet, conducting a reverse image search for a winter river scene similar to the stolen painting. Soon enough, he came across a picture of a throw pillow emblazoned with what looked to be the image of the lost Avercamp. He clicked the photo, zoomed in, and determined it was, in fact, the very same piece of art. He followed the link to a website that sells pillows, bedspreads, and posters with images of artwork on them. Schorer knew no photo of that quality could have been taken before 1978. Whoever took that photo, he thought, had the painting in their possession after it was stolen.

A throw pillow printed with the stolen Avercamp provided art hunter Cliff Schorer with his first clue as to who might currently have the painting. / Screenshot of print-on-demand art-merchandise site, Pixels.com

Schorer traced the photo’s metadata and found a 2012 copyright owned by an art library. That’s where his connections to New York’s art world came in handy: The metadata also named a New York art dealer who just happened to be an old friend.

Schorer put in a call. The dealer remembered the painting, explaining that it had been sold at a 1995 art fair in Europe—but by another dealer with whom he shared a booth at the fair. So how did legitimate dealers sell a painting that was reported as stolen? Turned out, the gallerist friend told Schorer, that the painting had been sold as a work by Hendrick Avercamp’s nephew and pupil, Barent Avercamp. Schorer surmised whoever sold the painting might have forged the “H” to look like a “B” in the ligature with which it was signed.

The mystery was unraveling quickly, but then Schorer hit a snag: The dealer who sold the painting thinking it was a Barent Avercamp had gone out of business. It took four months before Schorer made another breakthrough, tracking down the niece of the owner of the defunct gallery, who had inherited the archive. She dug through her papers until she discovered the record of the sale. She wouldn’t reveal the price, but Schorer estimates it was sold for under $200,000, far less than what it would have fetched had it been sold as a Hendrick and not a Barent—and a fraction of what it is worth today. Still, Schorer got what he wanted: the name of the people who had unwittingly bought the stolen painting.

Schorer soon learned that the Dutch couple who purchased the piece had passed away. So he tracked down their heirs and dispatched a letter in 2021 on behalf of the museum, expressing his hope they could find an amicable way for the painting to be returned to the museum.

The news of Schorer’s discovery thrilled the museum’s director emeritus, Jim Welu, who was a curator at the time it had been stolen from the Stoddards. An expert in Dutch art, he’d always hoped it would turn up. “Avercamp is a big name and this is a real ice-skating winter scene,” he said, adding, “We want the Avercamp back.”

Schorer waited for a response from the heirs, but has never heard back. In December, his Dutch lawyer wrote another letter giving them 40 days to respond and arrange for the return of the painting in exchange for the money they paid for it. If they do not respond, Schorer says, it will become a criminal matter in the Netherlands. Either way, a 44-year-old cold case may soon come to an end.

For Schorer, though, this is just the beginning. After all, he still has eight more paintings to find.

Related

Did a Boston Art Collector Find a Lost Rembrandt?

Cliff Schorer sure thinks so—and the dogged art detective won’t rest until he proves it.