The Many Faces of Boston Rap Star Oompa

"Black," "queer," and "from the 'hood" were the words that often described the Roxbury-born artist during her local rise to fame. But while Lakiyra "Oompa" Williams is all that—she's also a whole lot more.

Makeup by Ashley Cooper / Hair by Azekah Simon / Photos by Karin Dailey

It’s a Friday night in late March, and Oompa, the Roxbury-born artist, rapper, and performer is working out some excess energy, pacing around the makeshift greenroom and chatting nonstop. She’s getting ready to headline a show at Northeastern University, a short 30-minute set, and her manager, Jon Bricker, a 30-year-old white guy from Sharon that she and her friends affectionately call “Jon Snow,” warns that, as with most college events, there’s no telling what the turnout will be. Still, Oompa approaches the show with the same level of professionalism and all-in enthusiasm she would any other performance, including an hourlong sound check in the second-floor ballroom of the school’s Curry Student Center, which has a stage backdrop that she had Bricker coordinate with the Northeastern A/V team to change colors with each song. Her DJ for the night, a 28-year-old fourth-grade teacher by day named Brandi Chanel, is along for the ride.

“Check, check,” Oompa says into the microphone, and then, to the rows of empty chairs in the audience: “I don’t know why rappers always say ‘check, check.’ They already checked this shit.” She’s dressed in ripped jeans, a black T-shirt from the Malden streetwear store Laa Tiendaa, Ray-Ban sunglasses, and a Gucci crossbody bag filled with a phone charger, lip gloss and liner, lotion, a bottle of Burberry perfume, and some lavender, which she smokes out of tobacco leaf (“I’m a soft gangster,” she jokes). She’s wearing an oversize, diamond-encrusted nameplate around her neck. Her hair is in braids, a few of them dyed green, and her Air Jordans are untied as she takes long strides back and forth across the stage, swinging her arms, warming up, and psyching herself up. Side stage, her friends TLoui and Marlyn dance along and take videos for her to use later on Instagram and TikTok as Oompa runs through her eight-song set list, a mix of punchy, beat-driven tracks and slicker, bass-heavy jams, all with clever lyrics at their core.

Like all artists and all humans, Oompa is a lot of things all at once. Oompa the person is zero pretense: a funny, warm plant-mom with ADD and perpetually fingerprinted eyeglasses who taught herself to read astrological charts during the pandemic. She spends much of the pre-show hours in the student-center greenroom recalling Instagram stories she probably shouldn’t have posted. She’s an Aquarius, and when asked her age, prefers to say she’s “rapper years old” because everybody seems to want female rappers to be 25, and she’s already older than that.

Oompa the rapper, on the other hand, is a little tougher and, nearly without exception, described as a queer, Black orphan from Roxbury. These identities are real, and in today’s world, they have certainly gotten her places: Her earlier songs focused on her struggles growing up poor, gay, and out of place, losing a sister, losing her mom. These identities, she believes, have also enabled her to apply for and receive—with the help of her prestigious Bucknell University education and ability to write well—several grants from the city of Boston. They’ve also gotten her invitations to perform at Governor Maura Healey’s inauguration party, be a regular guest on WBUR and GBH, and even take over the Celtics’ halftime show. She can’t say for sure that her Blackness or her queerness have been the only reason for these opportunities for which she is profoundly grateful; she knows she has talent. But she can say for sure that she’s ready to no longer wonder anymore. She’s ready to just be Oompa.

As a result, this has meant shedding and rebelling a little bit from the expectations (and the safety) of being the Oompa she’s been known as until now. After years of identifying as more masculine in both musical and personal style—her second album was named Cleo, after Queen Latifah’s masculine lesbian bank-robber character in the 1996 movie Set It Off—she’s started to embrace her femme side: makeup, jewelry, accessories, eyelashes. She’s also leaning back into her given name, Lakiyra. Her latest single, “Think Too Much,” veers away from rap and hip-hop into something closer to Afro-Caribbean, and she sings on it—even though she’s still not entirely secure in her singing voice. “I’m not one of those people who don’t want to acknowledge all the identities that impact who I am,” she says. “But what I do want to be known as is an amazing person, and a great entertainer, and a wonderful businesswoman. I want to be able to be known as the things I give my life to work my ass off to achieve.”

With Governor Maura Healey at Healey’s inauguration party.

While the city has embraced Oompa for certain parts of who she is—which is to say, the more underrepresented parts, the parts that have challenged her—it’s unclear to her if that acceptance extends to all of who she really is. And that has made her question whether she’ll ultimately stay in Boston or go someplace else where she is just known as an artist and where being Black, queer, and orphaned isn’t considered the most interesting thing about her.

She’d stay if she felt like she could advance her career here—after all, Oompa is Boston to the bone. At every performance, she gives a shout-out to Roxbury. Yet for all the pride she has in her roots and the support that the city of Boston has given her, the question of whether the city will—or even can—sustain the artists it supports grows louder in her head each day. Grants, while incredibly helpful, she says, create a dependency in the absence of a thriving music economy. Meanwhile, some artists who receive opportunities based on identities can come to resent them. “I know that I check off a lot of boxes that people want when they’re looking for some kind of quota to be filled on diversity, equity, and inclusion,” she says. “I got ‘Black,’ ‘woman,’ ‘fat,’ ‘queer,’ ‘from the ’hood.’” Sometimes, she wants to represent those things; representation is necessary and important. Other times, she can’t help but feel a little used. “When somebody’s hiring me or interviewing me, I’m like, Are you doing this because queerness is at the forefront? Or are you humanizing me? And do you like my music? Do you like the art I put out? Do you see me as a full person? And a lot of times, the answer is ‘no.’”

To this end, as Oompa contemplates the next phase of—and home for—her career, she’s started to wonder: Is she part of a system in Boston that truly wants to support artists in whatever they do and however they choose to identify? Or one that just wants a way to feel good about itself?

Photo by Samuel Bennett

Oompa may feel she is too often defined by her backstory, but her story is certainly compelling. Born Lakiyra Williams in Roxbury, Oompa was put into foster care at six weeks old with a 60-year-old widow everyone in the neighborhood knew as “Ma.” Not long after, Ma—who worked at the Gillette factory and as a school-bus monitor, and lived in the low-income housing development Academy Homes—learned that Lakiyra’s biological older sister, Nicky, was a foster child in Mission Hill and decided to foster her, too. NooNoo, their biological younger sister, came a little later, and Ma also fostered her. “And then in ’95, she was like, ‘These are my kids,’” Oompa recalls. “She adopted us, and we lived with her ever since.”

Oompa grew up in a house where music was always playing: Bob Marley, Motown, and gospel. But as a kid, she never wanted to be a musician. She wanted to be a dancer, a lawyer, or a gang leader. She didn’t have role models at home for any of those paths, but her mother taught her how to be a hard worker and how to survive. For a long time, Oompa didn’t realize how tight her family’s finances were. “We knew we weren’t the best-dressed kids, but we never went hungry. Christmases were full; birthdays were full. We’d have our parties at Chuck E. Cheese or McDonald’s like everyone else, arriving in a limo because my godfather owned the limo company,” she says, adding that no one, not even Oompa and her sisters, knew they were loaned the limo for free. “We just thought we were ’hood-rich.” It wasn’t until she was in middle school when she started taking over some of the household responsibilities, including balancing the family checkbook, that she realized that they’d all been living on $833 a month.

It was also around that same time, when she was 12, that she was given the name Oompa. She was playing pickup basketball on the courts at Washington Park when an older male player who also frequented the courts started calling her an “Oompa Loompa Baby,” because she was “short and thick and a monster,” she says. Eventually, it got shortened to just Oompa, and a thinly veiled insult became a badge of honor. “I’d thought that everyone got a nickname on the court, but I found out later that it’s not standard; I got lucky,” she says. By 14, Lakiyra had all but been replaced.

Becoming Oompa was a relief. “Lakiyra was very insecure and hurt,” she says. “As Oompa, I started building a me that was as tough as I wanted to be. It was really nice to be like, Yeah, I’m Oompa. I’m all the things you said I am. And I’m fire.” She came out as gay that year—“I was dragged out,” she says, by her sister Nicky, who was forbidden from having boys over while Oompa hung out with girls their mom thought were just friends. Ma didn’t talk to her for two weeks. “Eventually, she was like, ‘I just don’t want you to have to suffer the same way that I have seen suffering,’” Oompa says. “‘You know, you’re already Black and a woman, and you don’t need to advertise anything else that’ll make you a target.’”

Still, Oompa discovered that being loud and out protected all the softest parts of her, she says; it protected Lakiyra. While Oompa was getting into fights in the neighborhood, Lakiyra was writing poetry, taking AP classes, and holding down afterschool jobs at the YMCA and TJ Maxx to help take some financial burden off her mom. In ninth grade at East Boston High School, her guidance counselor—“a weird lady who loved penguins and believed in me from day one,” she recalls—had Oompa take the PSATs. Oompa scored in the 99th percentile in the district and higher than anyone else in the school. “She pulled me into the office and said, ‘Do you know what that means?’” Oompa recalls. “‘It means you got brains. You gotta stop acting crazy.’” The counselor told her she needed to think about college; it was the first Oompa had heard of the idea.

To help her achieve that goal, the counselor nominated Oompa for the Posse Foundation scholarship, awarded to otherwise overlooked students with academic and leadership potential, which she won—along with a full ride to Bucknell University, a mostly white liberal arts school in central Pennsylvania. “I knew nothing about college,” Oompa says. “Nothing about academics. Had zero preparation.” Among her fellow students, she was noticeably Black, poor, and masculine, identities that suddenly became very visible and practically all that she or anyone else could see. “I was wearing the same clothes all the time,” she says. “I had locs, but nobody could do my locs out there, so they looked tacky.” She didn’t speak like the other students. She didn’t even know how to take notes in class. “There were so many things that just made me stick out,” she says. She constantly thought about leaving.

Then she was forced to. Oompa was playing basketball one day during her freshman year when she received a call from Ma. Oompa didn’t answer. Later that night, she learned Ma had died. Since Oompa’s older sister, Nicky, had died of lupus three years earlier, that left Oompa in charge of the house. She traveled home to take care of funeral arrangements, even though there really wasn’t any money for that, and took a leave of absence from school to care for NooNoo, who was still a minor. Oompa went to parent-teacher conferences and made sure her sister did her homework. It was a really tough time, she says, “making sure we had a place to sleep, making sure we had food in our bellies, and not doing really well at that.” Dinner was often a Jamaican beef patty shared multiple ways. Oompa lost 55 pounds from stress and not enough food.

Bucknell allowed her some time off, after which she returned to finish school. Oompa dropped her math major for English and education, which were easier to complete, and found a few mentors among the poetry professors. Life got better socially: She had friends and was popular, but there was a piece of her that understood that while she was certainly outgoing, likable, and fun, she was seen not in spite of, but because of, her differences. Playing them up didn’t feel great, but it made it easier to survive. “I was a very queer, Black, loud ’hood girl,” she says. “And everybody took note. At some point, I was like, ‘Okay, well, you’re not gonna fit in. So why not just love standing out?’”

After years of leaning into a tougher more-masculine persona, Oompa has recently started to embrace her femme side. / Photo by Karin Dailey

It was a hot Sunday morning in May 2022 when Oompa rolled into the Harvard Athletic Complex and onto the biggest stage of her career so far: the Boston Calling Music Festival, where headliners included Nine Inch Nails, Metallica, and Avril Lavigne. Backstage, the screen played her music videos as she got ready for her opening number, which featured dancers flipping across the stage in aerial cartwheels and back handsprings as she launched into the upbeat song “Amen.” At one point during the show, the dancers stripped down to black lingerie, and then Oompa pulled on a green Celtics jersey with her name stitched on the back as she performed one of her better-known songs, “Lebron,” a beat-driven track about the pro basketball player and “feeling like a bad bitch,” as she described to one music outlet.

Oompa had come a long way since her first time on stage during an open-mike night at Uptown, Bucknell’s campus nightclub, where she read and essentially rapped her poems. “I had this air of confidence,” she says of that first performance. “But something in me was trembling and just terrified.” Still, she was hooked. She found writing rhymes not unlike math—formulaic, rational—not to mention therapeutic. She found performing, meanwhile, both thrilling and validating. She’d spend nights in the computer lab learning how to use the program GarageBand, writing verses and setting them to beats. She started performing at open-mike nights whenever she could, on campus and around town.

After graduating from college, Oompa returned to Boston and took a job teaching eighth-grade English in Cambridge. At night, she wrote poetry and gradually worked her way onto spoken-word stages around Greater Boston. She was good—moving with a clear, powerful voice and unwavering presence—and audiences loved her. She entered several local and national slam poetry competitions and won—yet she eventually grew disillusioned with the scene. “A lot of slam was competition over who has the most important oppression and how awful things are,” she says. “It was like the oppression Olympics. A lot of people were getting hurt and tired. The truth is suffering is part of the human condition. We all hurt. It’s not a competition.”

When fellow musician Cliff Notez, founder of the Boston-based artists’ and performance collective HipStory, encouraged Oompa to record a mixtape of songs, she turned her attention from poetry to music and got to work putting together a collection of songs that might work for an album. She decided to start with a letter she’d written her mom in the years after her death in which she confessed her wish to have turned down the college scholarship to spend more time with her. She locked herself in the bathroom for two hours, and turned it into a song that expressed everything she’d left unsaid: “You wouldn’t of had to call me, I could’ve seen you then / but I ignored you to make a team that couldn’t win / To see you alive one more time or never again / At least then I’d have some closure I could settle with.”

Cover art for November 3rd

That song, “Dear Mama,” became the centerpiece of November 3rd, an album named for the day her mother died that Oompa self-released in 2016. The album received several positive reviews—including a nod as one of Dig Boston’s 30 Best Local Albums of 2016—which encouraged Oompa to focus her side art entirely on making music. She performed whenever and wherever she could, including small stages that don’t exist anymore, such as Wonder Bar. She began applying for artists’ grants to help fund her writing and performing. She told herself she’d quit teaching as soon as she earned an equal amount of money from her music. That happened in 2017, she says, “and I was gone.”

Oompa’s big break came in 2018 when she played her first sold-out show at Great Scott, the now-shuttered Allston bar and live music venue. She couldn’t believe that 250 people would show up to hear her play. “It changed something in my mind and gave me the confidence to keep going,” she says. Not long after, she answered an open call for submissions to perform at the inaugural Boston Art & Music Soul Festival, an event meant to amplify Black and brown artists and creators. That first year, recalls founder Catherine Morris, now the director of arts and culture at the Boston Foundation, she and her team received more than 5,000 applications for just 21 spots. Morris went to see Oompa perform live as part of the decision-making process. “Her performance was electric,” Morris recalls. “She had kids involved, grandmothers, aunties, everyone—and that really aligned with the energy I wanted to have for the festival.”

Morris wasn’t the only one singing Oompa’s praises: Later in 2018, she received the Unsigned Artist of the Year award from the Boston Music Awards. She used the momentum to release her second album, Cleo, which drew even more from her experiences growing up in Roxbury, and celebrated with a sold-out show at the 525-seat Sinclair in Cambridge. In 2019, Oompa took home the Live Artist of the Year award at the Boston Music Awards, and in early 2020, NPR named her a Slingshot Artist to Watch, describing her “hypnotic melodies and socially charged lyrics [used] to cultivate inclusivity and change the face of a sound dominated by the hetero-male perspective.” That time period, Oompa says, was a blur of hard work and constant hustle that paid off. “It just kind of felt like a bunch of oh-shit moments,” she says. “Like a dream.”

Oompa’s success, she says, “has just kind of felt like a bunch of oh-shit moments. Like a dream.”

It was a dream that was quickly becoming a reality. In the fall of 2021, Oompa released a third album, Unbothered, and spent time developing her live show, hiring a band, a DJ, and dancers. It paid off: In 2022, she opened for rapper 2 Chainz at Salem State and then took the stage at Boston Calling.

More big opportunities came in quick succession, including the chance this past January to perform at Governor Maura Healey’s inaugural ball alongside headliner Brandi Carlile. “One of the goals was to really celebrate Governor Healey’s historic election with talent that represents demographics that often get overlooked and also artists that would hype up the crowd,” says Mass Cultural Council executive director Michael Bobbitt, who was enlisted to help suggest guest talent. “I reached out to my staff, and Oompa came highly recommended. When I saw her work, I was blown away and so thrilled that we have an artist of that caliber in Massachusetts.” At the event, which was held at TD Garden, Oompa performed a five-song set that Bobbitt says lit the crowd on fire. “I imagined seeing her fill stadiums all over the world,” he says.

A pivotal moment in Oompa’s career was performing at Governor Healey’s inauguration party. / Photo by Samuel Bennett

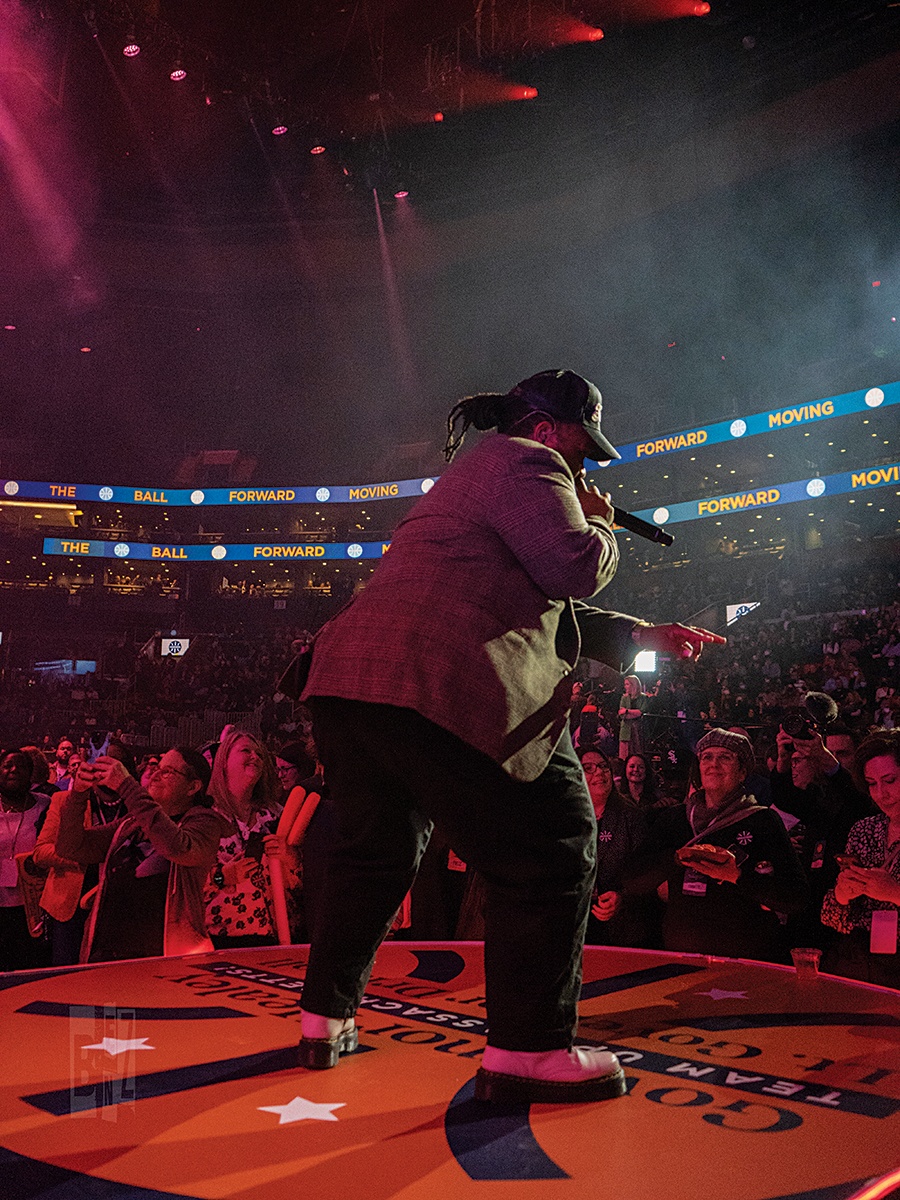

Later that same month, another call came in: Would Oompa be able to perform at halftime during a January Celtics game against the Golden State Warriors? The singer had come pretty far, but this was big—and it wasn’t just the size of the crowd or the significance of the stage. She’d recently connected with her birth father, who, it turned out, had been a popular R & B singer in the ’90s. She got to bring him to the game to watch her perform, where he sat courtside, second row, right behind Warriors point guard Steph Curry. “To be on the court at such an important rival game was one thing, but to be able to bring my people there,” she says. “I don’t always stay present to the moment. But when you’re with the people you love, and you see them taking it in, how they can’t believe that it’s happening, it makes you kind of come back home to that, like, ‘Oh my God, we’re here.’”

At Northeastern, the student crowd in the Curry Student Center ballroom was small, as Bricker had warned—fewer than 75 people. But those who did show up were into it—they knew all the words to Oompa’s songs and made little use of the rows of chairs, instead crowding right up to the stage. Oompa lit up the room with her music—stories rapped over electronic beats, danceable messages of empowerment—not at all deterred by the empty space or by the deafening silence after she called out, “We got any ’90s babies in the house?” and no one answered because these were all 2000s babies. She performed six songs before the mike went dead, creating panic for the A/V team. No matter: She freestyled a bit while Bricker tried to right the situation and made the most of what would have certainly been a disaster at a bigger show.

When he heard about the somewhat lackluster event, Dart Adams, a Boston music historian, author, and Boston contributing editor, was reminded of a conversation he’d had with Oompa five or six years ago. “I was telling her how when you’re disappointed by crowd turnout, you have to remember that there are instances in music history where there were acts that went on, and there were maybe 30 people in the crowd,” he says. “And after they performed, 95 percent of those people were their fans, and 75 percent went on to start their own bands or groups or careers. So you have to show up for every show because you’re making potential fans out of every person there, and you’re inspiring them at the same time.”

Still, being an inspiration is hard work, and it’s not always enough to pay the rent. Oompa’s not afraid of hustle, but some days she’s tired. She earns a decent living performing and fills in the gaps with artistic grants that ironically can, at least some days, seem to leave little time for making art, given the amount of time it takes to apply for them. While she’s grateful for these opportunities, she wants to know: “Where’s the money to pay your rent while you create beautiful things for the city and represent it well?”

Those are questions Oompa is asking herself as she ponders leaving the city she calls home, a city that may no longer have the runway for her to grow beyond the identities she has felt forced to lean into. Post-COVID, there are fewer live venue spaces for artists at her level. While many smaller venues didn’t survive the pandemic, the new venues that have opened in Boston—such as Roadrunner in Brighton and the MGM Music Hall at Fenway—seat thousands. “It’s like, once you sell out that 150-person venue, you better be ready for the 2,000-person venue,” Cliff Notez says. “That doesn’t make sense.” As a result, a good number of Oompa’s live performances these days have been confined to colleges and universities, and while Bricker says those can be very lucrative and help an artist grow a fan base, it’s not quite the same as performing at a traditional live venue, which is more prestigious.

The system, in other words, creates a dependency, making the city’s arts scene one that exists but doesn’t really grow or prosper. That’s an observation Notez and Oompa made a few years back while discussing the ins and outs of the local grant scene, which is often geared toward artists of color from underrepresented communities. There are rules, of course. “You have to create projects consistently, and you have to present yourself in a certain way,” Oompa says. “When you apply to these grants, sometimes they want a sob story. Sometimes it is tokenizing. Sometimes they want a narrative. Sometimes they want you to explore your identities and your troubles.”

Ironically, the grant application process can leave out a lot of the artists who could use the help the most. To be able to benefit from the system, Oompa says, “you have to have had access to institutions in the city and have a way to be able to communicate in a way that makes you seem worthwhile. So it leaves a lot of people out of the narrative—a lot of the ’hood kids, a lot of the non-readers, a lot of people who don’t care about college but who have a lot of great art to provide.” Kara Elliot-Ortega, chief of the Mayor’s Office of Arts and Culture, says that “artists should not have to share a sob story or trauma in order to get funding.” She also says that beyond grants, the city has strategies in place to support a creative ecosystem that includes, among other things, making new performance and cultural spaces and fueling nightlife and activities that draw people to the city.

Oompa is doing her part, with the city’s support, to help build that ecosystem. Last summer, she was one of 12 people and organizations awarded $500,000 in workforce development contracts as part of a program established by the city’s Mayor’s Office of Arts and Culture. She’s using the funding to establish Outlaud Entertainment, an artists’ collective and incubator that will mentor five emerging artists over the course of fifteen months. At the same time, roughly half a dozen creatives—including a photographer, makeup artist, a stylist, and art directors—will be a part of the collective, and paid for their participation in supporting the artists in the incubator. The idea is to give the artists the chance to work together—not on their own as grantees tend to do—network with one another and the industry people they meet through Oompa, and get a sense for how the industry works. The end goal? To help a new generation of artists break the cycle of dependency, and to serve as a model for the city to establish its own incubators or other hands-on approach to funding the arts. “We need more people who are in conversation with the culture in a real way,” she says. “We need to do more than just throw some money at it.”

The project tracks with Oompa’s career goals as a child, when she told herself that she wanted to be either a gang leader, a lawyer, or a dancer. “The idea of a gang leader keeps coming back to me, but as in a person who leads a community and who helps people find home wherever they are,” she says. “So, in that case, tokenize me. Come do it. Because I have a whole community of people who can benefit from that.”

Even as she works to grow the next generation of artists in Boston, Oompa acknowledges she’s ready for the next stage in her career. “I’m at a point where I’ve maximized my opportunities here,” she says. Last year, she applied for and was accepted to the Recording Academy, the music industry’s members-only society and the overseer of the Grammy Awards. A perk of membership is being able to buy tickets to the show in L.A., and that’s where she found herself this past February. Her seats were terrible, but it didn’t matter. “I’m up on, like, the third balcony feeling like I’m about to drop to the center of the earth,” she says. “I just put my glasses on and leaned over.”

It was outside of the show, though, where she grew convinced that L.A. is where she needs to be. “I met so many cool people in random places,” she says, recalling how she chatted up a music writer on a bus and saw Beyonce at a pre-party. “You could just be out eating chicken. You’re gonna meet somebody who’s somebody.” It’s the place where Oompa feels she has a shot at transcending the identities Boston associates with her—and maybe even becoming somebody who is somebody, too.

Alyssa Giacobbe is a New England-based writer and editor. Her last story for Boston was “3 Million Fans Can’t Be Wrong…Can They?“

First published in the print edition of the June 2023 issue with the headline “The Many Faces of Oompa.”