The Best High Schools

Walking the hallways of this $54 million school complex that rose last year in Massachusetts farm country 20 miles from the New Hampshire border is like taking a journey back in time. Amid the backhoes and dump trucks renovating the attached junior high, the campus is filled not with nose and navel rings, but with apple-pie complexions and Beaver Cleaver sensibilities.

“We're pretty sheltered around here,” admits one senior, Laura Ham, a blond-haired field hockey player with her eyes set on Amherst College. With a schedule packed full of advanced-placement, or AP, classes, she may well be the poster girl for the clean-cut student body of this three-town school district, which stresses a balance of academics, athletics, and community service. It's a combination that seems to be reaping dividends.

You may have never heard of Masconomet Regional High School. You may not even be able to pronounce it. (It's “Mass-ca-NAH-met.”) But admissions directors at some of New England's most selective colleges and universities know all about this gem of 1,100 students tucked into the northeast corner of the state. They consider Masconomet Regional High School — which serves Boxford, Topsfield, and Middleton — one of the best high schools, public or private, in the Boston area. It's one of several surprising opinions from the people who know better than anyone how our schools compare — and why some are doing a better job than others of preparing kids for college.

In a region where 43 out of every 1,000 residents are college students — the highest ratio in the country — it's hardly surprising that Greater Boston also has a dazzling array of standout high schools to ready its teenagers for the next level. But with the days long gone when kids automatically went to the nearest high school, the question of which one to choose can freeze ambitious parents in their tracks. Will one public school a give kid a leg up over another in college admissions? Does an elite private school enhance a student's chance of gaining entry to an elite college? The answer to both questions is probably no, and just asking usually makes college admissions officers bristle. Ultimately, they say, it's not about the school, but about the student. A straight-A student from Newton South who takes a full load of summer courses may, in fact, be less impressive than one with As and Bs and lower board scores who honed an interest in marine biology with an internship at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Colleges like schools whose students connect their academic interests to the outside world — by taking an AP course in government and then volunteering for a political campaign, for instance. “A student who's gone to a really well funded school, public or private, and just shows up for school every day will not impress us,” says Janet Lavin Rapelye, dean of admission at Wellesley College.

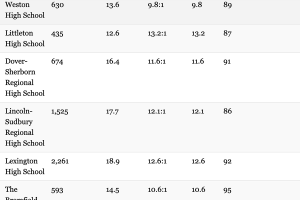

Admissions officers say some high schools just get it, and some don't, when it comes to finding the formula that works. The best have a low ratio of students to college counselors, for example — which is also one of the biggest differences between public and private schools. Some Boston-area private schools have as many as 1 advisor for every 5 students, while in local public schools the number ranges from 1 counselor for every 113 students in Quincy to 1 for every 389 in Swampscott. (The national average was 490 to 1; the Massachusetts average, 432 to 1; and the American School Counselor Association recommends a ratio of no more than 250 to 1.)

Of course, the availability of college counseling is determined largely by wealth, the single factor that has always clearly distinguished the best Boston-area high schools from the rest. But admissions officials argue schools compare on many other measures well within their own control. Overemphasizing advanced-placement tests, summer classes, and SAT scores is generally frowned upon, for instance, in favor of the broadest possible variety of course offerings, extracurricular activities, and real-world experience. “We look for intellectual curiosity — not just résumé-building,” says Nancy Hargrave Meislahn, dean of admission and financial aid at Wesleyan University. Going to Brown University's summer program one year and Harvard's the next may make a student look impressive on paper, she says, but it guarantees nothing when it's time for college acceptance letters to be mailed out.

Dick Nesbitt, director of admission at Williams College, routinely gets calls from nervous alumni who are moving, begging for advice about which school district to pick to ensure their preschoolers will get into Williams one day. “I tell them that wherever their children go, they're going to be well prepared for college,” he says. “If you look at the kids who are coming out of the really strong independent schools versus good public high schools, as far as how they do in college, there really is no difference. There may be a difference for the first semester or so, particularly for students from underresourced high schools. But after a semester or two, everyone is on a level playing field.”

Nevertheless, some high schools are simply better than some others. Last spring, just before school let out for summer at Masconomet, many of the college-bound seniors went missing from the campus, not because of a sudden outbreak of senioritis, but so they could spend the last six weeks pursuing internships under a program that lets students try out careers they might pursue. On the urbane end of the spectrum are internships such as “Principles of Banking,” “Trumpet Music,” and “Short Stories about My Grandfather.” But almost as a reminder of exactly where this school sits, the internships called “Window Framing,” “Animal Grooming,” and “Landscaping at Topsfield Fairgrounds” are no less popular.

Aside from the handful of black-shirted goths wandering the halls, mostly what you see at Masconomet are clean-shaven hockey players jostling with lacrosse and track stars. A few students gather in the state-of-the-art media center to produce the day's morning announcements, which are broadcast over television monitors that are mounted in every classroom. Teachers joke with students standing in line at the school's on-campus bank. In several of the computer labs, a steady tap-tap-tap can be heard from the keyboards of the Macs and PCs. And while there's no chalk dust around, since each classroom is outfitted with marker boards, multicolored scrawls detail physics formulas and literary conflicts. In the two-story library overlooking a glass-walled central courtyard, students lounge in chairs that seem especially designed for “teenage slouch.”

Masco, as the students call it, lies about 30 miles beyond the belt of high-power high schools, both public and private, that stretches from Weston to Lexington. But like the schools that hug Route 128, Masconomet has the same attributes that set great schools apart: an array of advanced-placement classes, from art studio to physics; well-trained teachers who feel supported by the administration; a range of extracurricular activities and real-world opportunities; and involved parents. It also has one more crucial educational asset: money.

An overlay of Greater Boston's finest public schools — the ones that pump a steady stream of graduating seniors into the Ivy League each year — aligns almost perfectly with a map of the area's richest towns. Masco may be a public school, but the price of admission is no bargain. The median cost of a house in Middleton, which students describe as the “ghetto” of the three towns that feed the high school, is $332,000. The median home price in Boxford, considered the “snobby” town of the district: $485,000.

The fact that money and good educations go hand in hand is nothing new. What is new is that the U.S. Department of Education expects the number of high school graduates to increase by 11 percent by 2010. Toss in a generation of affluent, determined Boston-area parents hell-bent on sending their children to the best colleges, and the already competitive contest for college admission becomes downright cutthroat.

Some of these parents opt for private schools — or “independents,” as they prefer to be known. The area's best independent schools cost as much as many private colleges, with annual tuitions of as much as $22,000 for day schools and $30,000 for boarding schools. Their student bodies are cherry-picked by administrators determined to create high-powered academic machines and bolster their reputations as the clearest path to the top. That doesn't necessarily mean they're the fastest route to the best colleges, however. Harvard could fill every classroom every year with nothing but applicants from private schools who have perfect GPAs and SAT scores. But, like all selective schools, Harvard tries to create classes with geographic, racial, and socioeconomic diversity, classes filled with academic, athletic, artistic, and musical standouts.

Like Masconomet, the private high school many admissions deans consider to have the most impressive intellectual offerings in Greater Boston is not well known. But if Boston University Academy (BUA) isn't a familiar name yet, give it time. Just beginning its 10th year, BUA is an infant beside private-school peers like Roxbury Latin and Phillips Academy, which are more than 200 years old. Yet it has quickly become a powerhouse, where SAT scores average 1,430 out of a maximum of 1,600 (the national average is 1,019) and students regularly perform as well as the college kids alongside whom they take classes at neighboring Boston University.

Clearly, out-of-the-ordinary smarts are a prerequisite for admission to BUA's class of about 30. But that's not enough. “They have to be nice kids,” says headmaster James Tracy. “We don't want a bunch of smart jerks. We're training extraordinarily capable kids with the best education that's available. If we were just training them to go on to be financially successful for themselves, I would have no interest.”

For the first few years of BUA's existence, students from the all-but-unknown school were not winning admission to elite colleges. “Parents sent their children here knowing that they'd have a better chance of getting into Harvard if they sent them to public schools to get straight As,” Tracy says. But as BUA's graduates have gone on to light up the academic boards at colleges across the country, highly selective schools are taking a closer look. Every Ivy League school sent recruiters last year, and BU Academy's 2002 graduates are headed for Amherst, Brown, Harvard, Johns Hopkins, Princeton, Wellesley, and Oxford University, to name a few.

“I came here for the academic rigor,” says senior David Goldin, who found the honors classes in his Newton public school “dumbed down” because, he claims, so many parents were calling the principal to make sure their children got into them. For senior Sascha Wiessmeyer, the appeal was an escape from the “weirdo” label she had acquired in the Weymouth public schools for being smart. “At BUA, you can develop yourself as an individual,” she says. “It's not conform, conform, conform.”

The biggest area in which BUA zigs while other high schools zag is the growing obsession with the advanced-placement program, which lets high school students take high-level courses and exams to earn college credit or advanced placement. “Our classes aren't geared toward the AP test,” says recent graduate Justin Meissel, a freshman on full scholarship at Washington University in St. Louis. “That would cheapen the experience.”

But most other high schools don't see it that way and continue full bore down the AP trail, boasting about how many students — not just seniors, but juniors and sophomores — are taking the exams. College counselors routinely review students' course selections to make sure they take on the rigorous workloads they hope will impress the colleges for which they're aiming. It may seem like a good thing — and, in fact, students who take AP courses tend to do better in college — but admissions directors worry it can also dampen students' enthusiasm. That was true for Jordan Smith, a recent graduate of Noble & Greenough, a private school in Dedham for grades 7-12. He recalls a counselor telling him during his junior year that he wasn't taking enough AP classes. “I dropped a history course about the Holocaust to take AP European history instead,” he says. “I wasn't too happy about it.” As proof of just how subjective the college admissions process is, college officials differ on whether Smith made the right choice. Some say he might have been better with the offbeat course since it interested him. But at least one says tougher courses make tougher students. “We'd rather see a student take a really rigorous AP class than a class without as much rigor and writing,” says Wesleyan's Meislahn. “He can take the Holocaust class when he gets to Wesleyan.” Maybe he will. After being recruited to row crew at Harvard, Smith chose Wesleyan instead. “I started thinking about where I would have the best college experience, rather than just focusing on the name game,” he says.

The name game is constantly changing anyway. At Nobles, director of college counseling Michael Denning says he struggles to convince parents that the reputations of certain undergraduates and colleges have improved over the years. “There are a large number of colleges that were previously thought of as commuter schools or regional schools that are now universities with national-caliber applicant pools and nationally recognized faculties,” says Denning. He cites Vanderbilt, Washington University in St. Louis, and Boston College among schools that have increased in stature in the last 20 years, and Carleton, Oberlin, Kenyon, and Pomona as small colleges with outstanding reputations. “We try to help kids and parents understand that great, small liberal arts colleges exist in places other than New England.” But as these schools become fashionable and more students apply, it only makes those students more competitive and adds to the admissions craze.

Newton South is routinely regarded as one of the region's top high schools, but it's notorious for its emphasis on AP classes. “There's no doubt it's a high-pressure school,” says Newton South principal Michael Welch. “High schools reflect the climate and culture of the community. This is a high-pressure community.” Top students at Newton South can choose from among more than a dozen AP courses, including music theory and statistics. Last year an astounding 20 percent of its 301 graduates scored a 3 or higher (out of a maximum of 5) on at least three AP exams. Fifteen students scored a 3 or higher on more than five AP exams, and one student even got either a 4 or 5 on eight AP exams. By taking the exams before their senior year, some say, their AP scores will make it onto their high school transcripts before they apply to college.

“My high school experience is geared toward getting into the best college that I can,” says Newton South senior Adam Katz, who hopes to attend Princeton or Duke next year. “I take AP classes, like AP bio, that I'm not interested in because I know it will help me stand out.” But the advice that college admissions officials have for Katz is that good grades and high test scores — including on the SAT and ACT, which are now de-emphasized or optional for admission to nearly 400 four-year colleges and universities, including Bates, Bowdoin, Mount Holyoke, and Wheaton — will simply keep him in the pack with the thousands of other straight-A students. They say it's what students do outside of their traditional academic studies that sets them apart, and the best high schools, public or private, are the ones that help students distinguish themselves beyond the classroom.

Phillips Academy, for example, is well known for its dance and theater programs. Newton South has two school newspapers and a school orchestra. BUA has a fencing team. Nobles has an option for students to spend the junior year in China, France, or Spain. And Masconomet boasts more athletic teams than Boston College.

Ultimately, though, it's not the athletic coaches, yearbook advisers, and orchestra leaders who influence students the most. It's the teachers, which is why schools are competing for them these days as much as they are for the best kids.

“Over time, the faculty is what carries the school forward,” says Stephen Carter, dean of the faculty at Phillips Academy in Andover. “The students come and go, but the faculty builds the school and its program.” Out of Andover's 200 faculty members, 40 have PhDs. Andover also lets its teachers take sabbatical leaves, and encourages research and writing over the summer.

At Masconomet, principal Pamela Culver is trying to find new ways to lure and keep faculty. Unlike most public high schools, Masco has PhDs, attorneys, and engineers among its faculty. The district has begun a mentoring program for new teachers that pairs them with veterans. Rookies have no administrative duties, like supervising study halls or homeroom, so they can focus on developing as teachers. “Teachers who apply here consistently tell me that they weren't getting enough support in their old districts,” says Culver. “We're trying to give them the support they need.”

Luke Butler, a Harvard sophomore and Lexington High School graduate, fears his high-powered alma mater may be slipping because of an exodus of veteran teachers. In the past four years, he says, he watched the principal leave for Weston High School, the superintendent, for the Newton Public Schools, and several “legendary” teachers depart for Concord-Carlisle and Weston high schools. But Butler is satisfied that even if Lexington slips, it will slip only so far. “One thing Lexington is famous — or infamous — for is Lexington parents,” he says. “They're fighting hard for their kids. They won't just let the school system deteriorate.”

It's a system, he says, that prepared him well for Harvard. “The thing I was most prepared for at Harvard was the pressure,” he says. “Most of my friends at Harvard are used to being the best in their class and getting straight As. They don't know how to reconcile themselves with the fact that they're not going to get all As at Harvard. I already learned to accept that at Lexington, where very few people get straight As.”

Having access to knowledgeable college counseling can make a tremendous difference not just in a student's experience in the admissions process, but actually in getting in. This, say many university admissions deans, is what parents are buying when they send their kids to private school. In many public high schools, guidance counselors today also have to help kids deal with everything from problems of substance abuse to unstable home lives, eroding the time they once allotted mainly to helping students select a college — and to persuading colleges to admit their students.

Private schools are renowned for lobbying colleges on their students' behalf. Some send their college advisors jetting around the country to make personal visits to university admissions deans. But guidance counselors at the best public high schools also rub elbows with college admissions officers, getting to know them on a first-name basis at college fairs and admissions conferences and making regular calls to emphasize what a transcript may not reveal about a student.

“I play a supportive role for the students,” says Leonard Emmons, Masconomet's director of guidance, one of six counselors who work with a senior class of about 250 students. “You've got to sell your product. We work with admissions officers to tell them what we have. A lot of students look alike.” Emmons shrugs when asked about the growing trend of parents' spending thousands of dollars to hire outside college counseling consultants. “We've known these students since they were in the ninth grade,” he says. “It's more important to know the student than to be a college expert.”

College admissions officers agree. “At the most selective colleges, there isn't going to be communication between the independent counselors and the colleges,” says Williams's Dick Nesbitt. “We wouldn't put as much stock in it.” Adds William Hiss, vice president for external and alumni affairs and former dean of admissions at Bates: “In general, I have not been enthusiastic about private counselors.”

He may not be. But parents are, and as the ranks of college applicants grow, new companies offering better test results, improved interviewing skills, and more impressive-looking transcripts are cropping up each week, fueling the admissions hysteria. In the end, the best high schools may well be the ones that keep that mania to a minimum.

“Thankfully,” says Newton South's Welch, “we spend most of our lives not in high school.”