An Algorithm “Diminished Integration” at Boston Schools, a Report Found

The new system did not fix inequality in the city and reflects "a potentially troubling trend."

photo via istock.com/Lisa-Blue

An MIT-designed algorithm intended to make access to good schools more equal in Boston did not achieve its goal and in fact “diminished integration” in the district, according to a new report from Northeastern’s Boston Area Research Center.

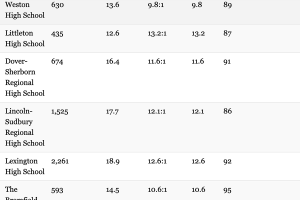

The study, commissioned by Boston Public Schools, analyzed the success of a new “home-based assignment system” approved in 2013 and launched in 2014, which was created to give parents a list of options for elementary and middle schools that took into account where they live and whether the schools were higher- or lower-achieving based on test scores. It sounds OK on paper, but, researchers realized, Boston’s unequal distribution of good schools proved too difficult an obstacle for the computer system to overcome, and it remained likely that sections of the city that are less affluent and where there are larger populations of students of color—including parts of South Boston, Roxbury, Mattapan, and Dorchester—remained disadvantaged, while white and Asian students in wealthier neighborhoods had better access to better schools.

“Geography largely determines access to quality,” the report, which was presented to the Boston School Committee Monday night, reads. “[I]t is impossible for a choice and assignment system to provide access to ‘good schools close to home’ when the geographic distribution of quality schools is itself inequitable.”

The algorithm was successful in achieving one of its goals, though, as the distance on average that students had to travel to get to school reduced, but the report found that in a city that is already starkly separated along racial and economic lines, schools still reflect that reality.

Researchers stressed that the results were “not alarming,” given the pre-existing make-up of the school system, but wrote that “they do reflect a potentially troubling trend.” To help, researchers suggested that redesigning the system to take into account how competitive the enrollment process is at each of the schools, but, generally speaking, it noted that the district can only really address inequality by improving schools citywide. In other words, if what we want is a perfectly equal school system that doesn’t penalize you for growing up in one neighborhood instead of another one, a computer system alone won’t get us there.

Boston civil rights groups have responded to the report with alarm. In a joint statement, groups that include the Lawyers’ Committee of Economic Justice and the local branch of the NAACP, vowed to fight for more equitable education in the city. “It has only been 44 years since the City of Boston put a stake in the ground against legalized school segregation – barely a generation,” they said. “Our neighborhoods remain racially segregated today. To think that a city as racially segregated as Boston would be positioned to adopt a neighborhood school model, while also cutting access to transportation that would help secure integrated schools, is morally and ethically devoid of racial consciousness. Boston waited far too long to understand the impact of its student assignment system, and students of color disproportionately bear the harm of that mistake.”