Is This the End of the High School Varsity Jacket?

Letterman jackets used to be for winners and cool kids. In today’s high schools, they’re about as popular as leg warmers and big hair. What happened?

Illustration by Benjamen Purvis

As the days become cooler and leaves start to fall, a wave of nostalgia washes over me as I watch my 16-year-old twin boys head off to a Friday-night football game under the lights. Not much has changed since our own parents dropped us at the ticket gate decades ago—lowly freshmen are still relegated to the farthest reaches of the bleachers, and upperclassmen still spend half the game trying to figure out where the afterparty is—but there is one notable difference: Very few kids in the stands are wearing varsity jackets.

What was once the ultimate teen status symbol is no longer.

I learned this last spring when my boys, both high school swimmers, received an email from their athletic department congratulating them on earning a varsity jacket. “That’s so exciting!” I gushed, immediately picturing my teen crush Emilio Estevez in his blue letterman’s jacket in The Breakfast Club. “When can I take you guys to get fitted?”

“Mom, I don’t even know if I want a jacket,” one of my boys replied dismissively.

“Yeah, I’ll think about it,” added the other.

I was dumbfounded. What do you mean you’ll think about it? What was there possibly to think about?

A varsity jacket was the epitome of cool back when I was growing up in the late 1980s in suburban Washington, DC. If you wore a varsity jacket, you were an athlete. You had status; you belonged. A jacket gave you swagger, whether you deserved it or not. When a girl walked into a party wearing her boyfriend’s jacket, his name embroidered in cursive on the front, you desperately wanted to be her, or the lucky guy who gave it to her. And, of course, what would a John Hughes movie have been without a posse of varsity-jacket-clad jocks crowding the hallways and populating the detention rooms? The writer-director’s portrayal of the teen social hierarchy depicted the angst of an ’80s adolescence so perfectly that it felt like he was right there beside us, in our short shorts and knee-high tube socks, taking notes in third-period gym class.

But back to today. Curious whether athletes at other schools in the Boston area are eschewing the varsity jacket, I reached out to my friend’s son—a senior at Lexington High School who’d lettered in lacrosse his freshman year—and asked how often he wears his. He looked at me blankly. “I don’t have one,” he replied finally.

“Wait, aren’t you the captain of the lacrosse team?” I asked.

“Yeah,” he responded, “but I’ve never been offered a jacket.”

“But do your friends have varsity jackets?”

“No.”

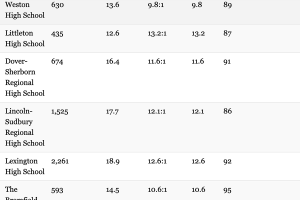

Surprised, I dashed off an email to the director of athletics at Lexington High School, Naomi Martin, who confirmed that while the football and boys’ ice hockey teams’ booster clubs offer their players the opportunity to purchase letter jackets, “other sports have typically not been interested.”

Casting a wider net, I posed the question on Facebook, where I was flooded with nostalgic replies from adults. (So many of us still have our well-loved jackets in the backs of our closets, just waiting for our next high school reunion or Halloween party.) Ultimately, though, the consensus—from as far away as the San Francisco Bay Area—was that for high school students today, varsity jackets are out.

So why aren’t kids wearing letter jackets anymore? Don’t bother to ask a teenage boy, or you’ll likely get the same brusque response I did: “I don’t know, Mom, they just aren’t.” (Read: Buzz off.) When I ask other high schoolers, I hear a few half-hearted assertions that the letter jacket is a symbol of the patriarchy—the embodiment of females’ submissiveness to dominant males. But that perspective feels dated in 2022. Girls have been earning their own varsity letters since I was in high school and well before. As much as I’d longed to wear a boy’s jacket, I’d been equally determined to earn my own by making the girls’ varsity soccer team.

What is different is that athletic prowess is no longer the sole measure of popularity, as it was 30 years ago. Back then, smart kids were deemed “nerds,” and athletic kids were “cool.” It was very one-dimensional. You were either an athlete or a student—hardly ever both (or if you were, you hid it well). These days, well-roundedness is valued more: Kids who participate in numerous extracurriculars and excel academically are at the top of the pecking order, according to the teenagers I spoke with.

In addition, while those cadres of mean girls and bullies that used to rule the school garbed in their varsity jackets still exist, they don’t wield the power they used to. “Everyone knows those kids,” acknowledges Grace, a high school senior, “so they’re popular in a sense. But no one likes them.” We never liked those kids either, and yet we’d dutifully chauffeur them to parties, let them copy our homework, and flatter them with the attention they so clearly craved. Thankfully, our own children seem to be less tolerant of this behavior that we simply accepted as the norm.

Moreover, there’s a push toward inclusivity that didn’t exist 30 or so years ago. Kids are taught to appreciate the diverse identities, interests, and talents that make up the entire high school community. So if the school’s robotics team makes it to nationals—or the debate team makes it to the Tournament of Champions, or the a cappella group wins a regional competition—there’s nearly as much hype as if the lacrosse team wins States. Everyone’s achievements are recognized. To wit: In some schools, upperclassmen can now letter for band, yearbook, choir, and even the arts.

As a kid who made As in honors classes but only just made the cut for any sports teams I went out for, I’m thrilled by this reshuffling of the high school hierarchy. Yet I suspect it’s hastened the demise of the varsity jacket. Back in the day, it was a “huge deal” to receive a letter for sports, recalls Nathan Atherley, a father of two teens who coveted a varsity jacket for years before finally earning one for football. It was physically demanding and time intensive, and you had to be focused and extremely disciplined. It wasn’t a goal all students could achieve—and that was okay. Now, if nearly everyone can earn a letter, it seems like it’s “been devalued,” says a former Belmont High School football player. “I get why no one wants one anymore.”

Still, our kids don’t see it that way. Instead, one senior explains that she’d feel “cocky” wearing a varsity jacket to school. Her words give me pause.

“Isn’t that kind of the point?” I ask.

Nah, she says: “I know I earned it. Why do I need to wear it?”

I’m reminded that these are “we-” not “me-” focused Gen Zers. While they still grapple with social pressures such as cyberbullying, they’re capable of humility and acceptance in a way we never were at that age. We were too worried about what others thought of us—too locked into stereotypes and confined to our cliques (whether it was the goths, punks, jocks, nerds, or theater geeks) to branch out. These days, nearly every member of a class is connected via social media, so the lines between groups have blurred.

I have to admit that I’m sad to see the letter jacket go. No doubt it’s partly an ego thing: It hurts our feelings when our children don’t appreciate something we once held sacred. But that seems to happen with every successive generation—family dinners, anyone?—so maybe it was inevitable.

Or maybe not. Coming off remote learning, many teens are still feeling adrift. They could use something tangible to latch on to—to help them feel a sense of belonging and connectedness that’s vital to emotional well-being. Numerous studies have shown the powerful effect that community participation can have on mental health. When we feel part of something bigger, we thrive. Schools can help fill this gap with the right programming. Perhaps now is the time to revive some tried-and-true traditions like school dances, pep rallies, and, yes, even varsity jackets to help foster interconnectedness in real life, not just online. (Maybe that’s why Louis Vuitton’s fall menswear show in Paris was chock-full of them.)

At least, that was the argument I used to finally convince my boys to roll the clock back and get fitted for a jacket—“What’s the harm in trying one on?” I asked. I swear I could hear the first few chords of “Don’t You (Forget About Me)” playing as they slipped their arms into the jacket sleeves and flexed for the mirror. I hadn’t seen such genuine smiles in a long time, and I felt myself tearing up unexpectedly. It’s been a rough few years, and our kids have missed out on so much. Here was a sliver of pure, unadulterated joy—and pride—however fleeting.

I walked up to the counter and ordered two.