Can Altering A Protein Help You Burn More Fat?

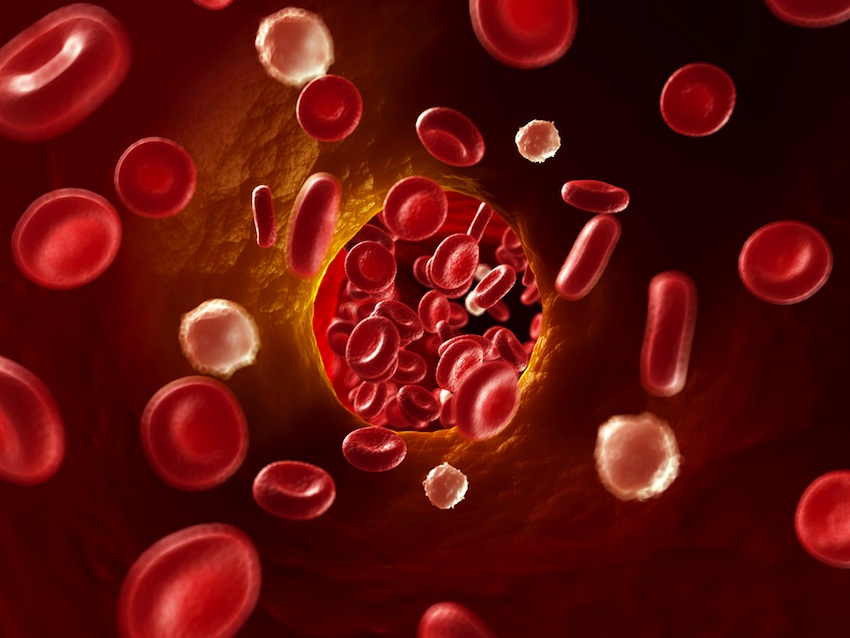

Fat cells photo via Shutterstock

No matter how disciplined your diet or how rigorous your workout schedule, your figure comes down, in large part, to your genes. (Cue gratitude or frustration with Mom and Dad here.) And while that may be true, Harvard Medical School (HMS) researchers may have found a way to spur bodies that were formerly prone to storing fat into burning it.

The researchers, who published their findings in the journal Molecular Cell, pinpointed a protein found in the mitochondria, the part of the cell often called the “powerhouse,” that regulates how much fat is burned and how much is stored to give the body energy. A team led by HMS cell biology professor Marcia Haigis genetically programmed mice to lack this protein, called SIRT4, and found that the altered mice burned more fat, exercised longer, and stored less fat than mice with natural levels of SIRT4. In a report from HMS, Haigis says:

“This is a first step in our mechanistic understanding of how SIRT4 affects lipid metabolism by modifying a little-understood enzyme,” Haigis said. “SIRT4 really affects the balance between fat oxidation and breakdown or fat synthesis and storage…”

And while this news is certainly exciting, Haigis cautions in the report that quite a bit more study is required before SIRT4-suppressing drugs become a dieter’s best friend. Plus, she notes that fat burning versus fat storage isn’t the only aspect at play in common diseases like obesity and diabetes; blood sugar levels, for example, were just as high in the genetically engineered mice as in the control group, and blood sugar can also lead to health problems. Nonetheless, she says the research is an exciting step forward:

“It really highlights the central role of mitochondrial metabolism,” she said. “The more we learn about these metabolic shifts in the mitochondria, the more it’s like peeling back layers of an onion. We have more to learn, but what we know already touches a lot of areas of human biology.”