Frozen Poop Pill May Be Effective Treatment for Infectious Disease

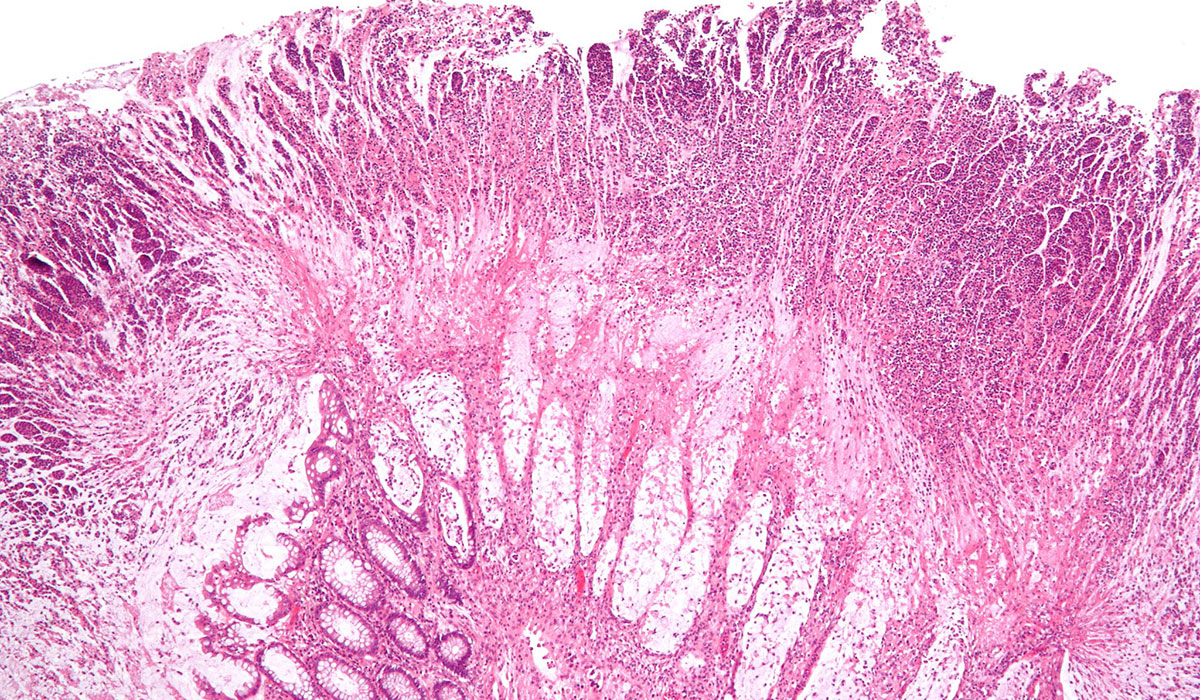

Magnified view of the Clostridium difficile infection via wikimedia commons. Researchers used the pill to treat symptoms of the infection.

In conjunction with scientists at Tel Aviv University in Israel, researchers from Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston Children’s Hospital, and Harvard Medical School are studying what is described as a “frozen poop pill” as a potential treatment for infectious disease. The poop pill, technically known as “fecal microbiota transplantation” (FMT) is in an encapsulated form, and has shown promise as a less-invasive alternative to other FMT delivery methods such as a colonoscopy or the placement of a nasogastric tube.

“Delivering healthy, pre-screened donor stool is complicated,” says George Russell, a physician and researcher at Boston Children’s Hospital. “The idea behind the pill is that it’s a very easy mechanism to deliver the donor stool without need for anesthesia, without need for invasive procedures, without the cost of any of those procedures, [and without] time away from work.”

But what good can donor stool do? Russell explains that scientists are just beginning to understand the role played by the bacterial gut ecosystem in regulating health and disease. By modifying this ecosystem, Russell says there is potential to improve outcomes for various autoimmune and metabolic diseases.

“In a recurrent infection called Clostridium difficile [a debilitating condition characterized by diarrhea and abdominal pain], there is a very clear disruption of the gut flora that can be corrected by replacing healthy stool into a recipient and re-balancing the gut so that the infection can’t recur,” Russell says.

Scientists in Boston and Tel Aviv used Clostridium difficile, also known as C. diff, as the starting point in their research on the efficacy of the frozen poop pill. In a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, Russell and his collaborators found that the symptoms of C. diff were successfully treated with the pill in 90 percent of patients. These results are important because they establish what Russell calls “proof of concept,” that FMT can be administered effectively (and safely) in pill form. Still, with the study’s sample size limited to just 20 patients, there is much more research to be done.

“We’re really in the infancy of this. We’re trying to figure out why this works to understand how transplanting healthy stool changes the gut microbiome and how long it can change the gut microbiome,” Russell says. “This is all brand new, but it’s exciting and it offers us the potential as clinical researchers to hopefully offer patients new therapies.”

Now that researchers have had preliminary success in using the pill to treat C. diff, Russell says he plans to explore the pill’s effectiveness in treating inflammatory bowel diseases such as Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis. Other scientists, Russell says, are looking into the pill’s usefulness in addressing food allergies and autism. A word of caution though: Don’t try this at home. Russell says people have used the Internet to learn how to make their own versions of the poop pill, an act which according to Russell is very ill-advised.

“This should be done in a scientific, rigorously controlled study approved by the FDA where both safety and outcomes are followed closely,” he says.