A Northeastern Professor Is Using Nanotechnology to Fight Zika

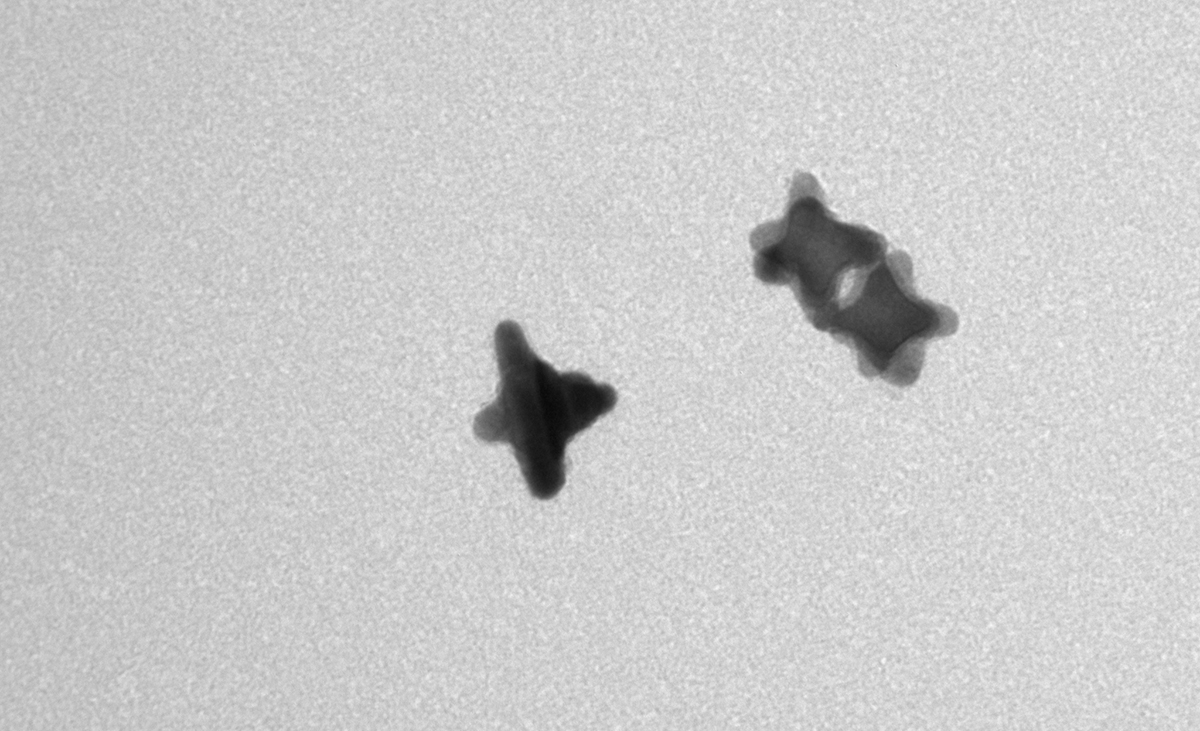

Nanoparticles/Photo provided

On Monday, CDC Principal Deputy Director Ann Schuchat said the words many have dreaded since the Zika outbreak began. “Everything we look at with this [Zika] virus,” she said, “seems to be a little scarier than we initially thought.”

In a lab at Northeastern University, Tom Webster is trying to combat those fears. Webster, chair of Northeastern’s chemical engineering department and the president of the Society for Biomaterials, is using nanotechnology to develop potential cures not only for Zika, but for diseases of all kinds.

“They have the E-ZPass for everything in your body,” Webster says of nanoparticles. “That property makes them incredibly exciting [for] delivering drugs in places we never thought we could deliver drugs.”

It also makes them a good tool for targeting diseases like Zika, viruses that are nano-structured—that is, similar in size and scale to the tiny particles Webster creates in his lab. His team’s most promising project, he says, involves creating nanoparticles that can attach to the Zika cells, preventing them from multiplying inside the body.

“By simply attaching them [to the viral cells], we keep them from entering cells, and we keep them from being active to replicate inside of cells,” he explains.

Plus, unlike vaccines, which can’t keep up with viral mutations, Webster’s technique—which he says could be ready for clinical use in about five years, if not sooner—could adapt to any form of the disease it finds in the body. That means the particles could treat the Zika strains of 2020 just as well as the Zika strains of 2016.

“The influenza mutates every year, and that’s why we never have a 100 percent good flu vaccine,” Webster explains. “In our nanoparticle approach, it doesn’t matter, really, how it mutates. We can basically use that nanoparticle to always attach to that virus no matter what the stage of mutation is.”

Complementing that work is a new partnership between Northeastern and Colombia’s University of Antioquia. The pairing is meant to combine Colombian expertise in tropical plants and their medicinal powers with Northeastern’s expertise in nanotechnology and drug delivery.

“We partnered with them to use their proteins, put them in our nanoparticles, and now we have a good system where we can deliver these entities that could help keep the virus from spreading inside a person,” he says.

Webster’s lab is also at work on two projects that sound like science fiction. One—which Webster says may actually be useable within three to five years—would use nanoparticles to change the fluorescence of disease cells. Once that’s done, a fluorescent wand could detect the presence of those particles on keyboards, countertops, phones, and more. “You can’t think of just treating the virus,” Webster says. “You also have to think about detecting if it’s even there to pose a problem.”

Once it is there to pose a problem, however, another in-development project could reverse its effects. The research is at least 10 years out—Webster calls it “Star Trek-vision” status—but, if successful, it could revolutionize the treatment of everything from Zika to cancer.

Webster and his team are trying to develop synthetic immune cells that would boost ailing immune systems, providing extra ammunition in the fight against disease. “These synthetic immune cells would go around your body, and they would identify when you have a virus present and immediately attach to it, engulf it, and clear it from the body,” Webster says. In short, they’d do what the sick body could not.

And while that project could be used for Zika treatment, its implications are far larger. Webster says the cells could target any disease, even chronic conditions like cancer and HIV.

“Anybody who’s suffering from a disease, whether it’s related to viruses or not,” he says, “has problems with their immune system.”