A Reboot for the Boston Globe?

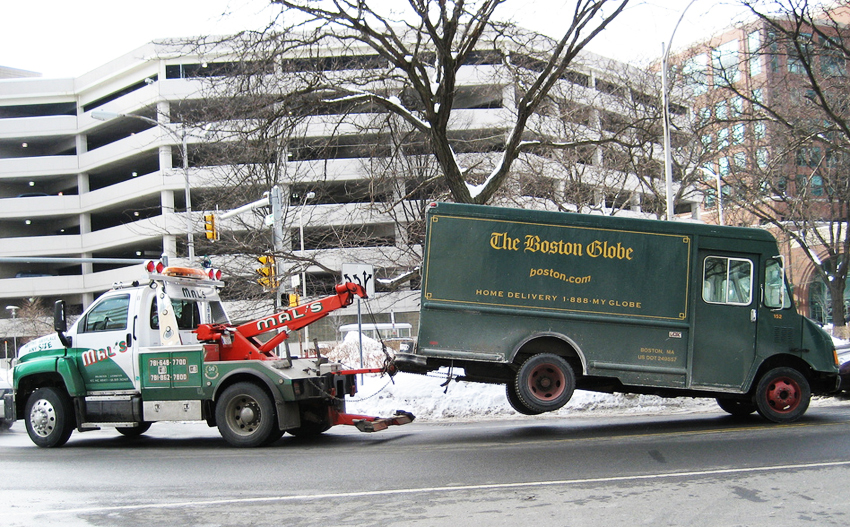

Photo by jtu/Flickr

Twenty years after buying the Boston Globe for $1.1 billion, the New York Times Company has announced that it will sell the paper. Globe journalists learned of the news the same way the rest of us did, via a tweet from Bloomberg News: “BREAKING: New York Times Company said to put Boston Globe up for sale.”

The move itself wasn’t exactly a surprise. Four years ago, the Times Company explored a sale before finally deciding against it. What’s more, Janet Robinson—the Times Company’s former president and CEO, and a one-time Somerset schoolteacher—had been one of the Globe’s staunchest defenders in New York, but she left the company in 2011. Staffers have understood since then that their days in the Times fold were probably numbered. Still, the way the news broke was jarring.

“We had heard the rumors for years, and strongly suspected that at some point there would be something to them,” says the Globe columnist Adrian Walker. “But we certainly didn’t think anything was imminent. We were also taken aback by the way we found out…. [It] was a shock.”

It shouldn’t have been. In 2009, when the Times Company threatened to shut down the Globe unless it received $20 million in union concessions, the story was broken not by the paper itself, but by WBUR and the Boston Phoenix. (I worked at the Phoenix at the time, and got a tip from an incredulous staffer who’d discovered the ultimatum.) Making matters worse, while members of the Boston Newspaper Guild waged a bitter internecine battle over whether to give in to the threat, the chairman of the Times Company, Arthur Sulzberger Jr., and his colleagues in New York floated above the fray, keeping their distance instead of traveling to Boston to make the case for sacrifice. When it came to the Globe, Sulzberger and friends didn’t seem to see frank, respectful communication as a big priority.

Consequently, it’s no surprise that some Globe reporters and editors are welcoming the prospect of life after the sale—especially if it means restoring the paper to local stewardship. “Being owned by somebody who actually wants to own us would not be a bad thing,” Walker says. “And I think people who’d be most passionate about the Globe—who would see us as something more than a property in their portfolio—would be local owners. So hopefully that will happen.”

As the Globe saga plays out over the next few months, however, all of that optimism should be tempered with a healthy dash of realism. It’s true that the next owners of the paper, whoever they wind up being and wherever they happen to live, may have a greater emotional stake in its success than the Times Company ever did—and that, as a result, they’ll treat the paper’s employees with a greater degree of respect. That said, one uncomfortable fact should be acknowledged: During an absolutely brutal period for daily newspapers, the Times Company shielded the Globe from the worst ravages of the industry. The new ownership may not be so accommodating. It may be hard to believe this right now, but in five years we may all remember the Times years as the good old days for the Globe.

In 2001, when Marty Baron arrived from Miami to become the paper’s new editor, the Globe had 513 newsroom employees—a number that soon after rose to 547. Today, it has 360. That’s a big reduction, to be sure, but it’s nothing compared with the cutbacks seen by similar papers over roughly the same span. Ken Doctor, who was an executive with Knight Ridder back when that chain of newspapers was one of the most respected in the country, and who today is a newspaper-industry analyst, calls the past decade a “carnage.” The Los Angeles Times, Doctor says, has gone from roughly 1,300 editorial staffers at its height to 500 today. It’s the same story across the country. According to Doctor, staffing at the Baltimore Sun has dropped from roughly 400 journalists to fewer than 140; at the Hartford Courant, from 475 to 135; at the Tampa Tribune, from more than 200 to 90; and at the San Jose Mercury News, from 425 to fewer than 150.

But the Globe’s relatively robust staffing tells only part of the story. Newspapers are struggling today in large part because they were so slow to adapt to the Internet, and many of them now lack the resources to catch up. Under the Times Company, though, the Globe has been able to make smart, aggressive investments in digital distribution.

Doctor says Times Company money has also helped the Globe adhere to its core mission. “They were able to keep their accountability journalism going,” he says. “Not just long investigative pieces, but the sense the paper has that it’s responsible for the citizenry—that it’ll delve into what’s going wrong, and shine a light on it.” Given the paper’s recent achievements—among them its takedown of the former House Speaker Sal DiMasi, its scathing look at patronage in the Massachusetts probation department, and its massive multimedia series on Boston’s troubled Bowdoin-Geneva neighborhood—that assessment rings true.

But it’s not just what the Times Company has allowed the Globe to do—it’s also what New York has protected the paper from. The past decade has seen more than just massive attrition at the nation’s daily newspapers. It’s also been full of plot twists that teeter somewhere between tragedy and farce.

Take what’s happened in Philadelphia, where that city’s analogs to the Globe and Herald—the Inquirer and Daily News, respectively—have been jointly owned for decades. In the past seven years, the papers have had a total of five different owners. One group was led by Brian Tierney, a Republican operative turned PR executive known, among other things, for aggressively battling the Inquirer on behalf of the Philadelphia Archdiocese. (Under his watch, the Inquirer added both Rick Santorum and John Yoo, President George W. Bush’s torture theorist, to its stable of columnists.) The current owners, meanwhile, include the influential local businessman Lewis Katz as well as George Norcross, an insurance executive described by the Inquirer—before Norcross became a partial owner—as a “South Jersey Democratic boss.”