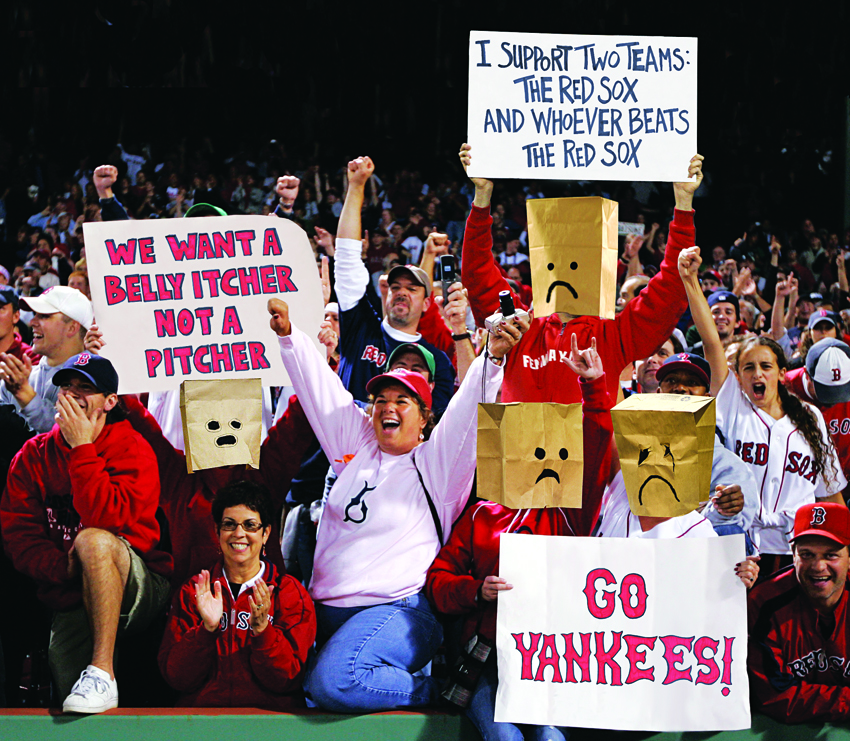

Root, Root, Root Against the Home Team

Photo Illustration by Callie Atchue

In late October of 2011, the Chicago Cubs held a press conference to announce the hiring of Theo Epstein. It was a lot like the one the Red Sox had held nine years earlier, when they first promoted the 28-year-old to general manager. And while the Cubs’ new savior had just fled Boston amid all the bitterness of the team’s September collapse, he was still able to reminisce about his favorite parts of running the team. “The first thing was helping build a scouting and player-development machine from the ground floor,” Epstein said, alluding to the way baseball teams draft and develop their future stars.

The second, of course, was winning two World Series. But stop and think about this for a moment: When asked to reflect, the Boy Who Uncursed Boston’s first instinct was to talk wistfully about draft picks.

Epstein was right to be proud of his “machine.” For a decade, his Red Sox had proved better than anyone at acquiring elite prospects, including Dustin Pedroia, Jacoby Ellsbury, the Jonathans (Papelbon and Lester), and others who played crucial roles on Boston’s best recent teams. But those players weren’t simply the result of Epstein’s eye for talent. He was able to use Boston’s considerable financial muscle to bend Major League Baseball’s draft rules—essentially, to buy extra top draft picks.

Now baseball has cracked down on this big-money practice. That means the post-Theo era will be far more challenging than most fans realize—and that Epstein’s replacement, Ben Cherington, will have a much tougher time finding Boston’s next batch of stars. In fact, the smartest move would be for the Red Sox to restock their farm system through the only sure-fire method they have left: losing, and losing badly. Sure, another playoff-less season might lead to some pain, but it would also lead to better draft picks, better free agents, and a better long-term future. Instead, the Red Sox have signed a number of midlevel free agents—the types of players who will make the team more palatable to NESN viewers, but not help it contend. In short, the Red Sox are neither good enough to win now, nor bad enough to win in the future.

Before we get to exactly why the Sox should tank, let’s break down baseball’s draft. Teams pick in order, worst to first, but unlike the NBA and NFL, which limit the salaries of their picks, for decades MLB let its franchises spend whatever they wanted. Traditionally, they wanted to spend very little, and the draft provided the sport’s best bargains. But starting in the 1990s, a few top prospects began making seismically unsubtle hints about their contract demands—hints that scared off baseball’s bottom feeders. Those players fell to the better, richer teams, with the cagiest ones happily spending more to gobble up the best talent.

In 2000, baseball commissioner Bud Selig decided to fix the system. His office began spelling out the preferred bonus for each draft “slot.” (Bonuses are how drafted players receive the bulk of their payment.) In the 2012 draft, for instance, the first pick overall was supposed to get around $7 million. Players taken at the end of the first round were slotted for $1.5 million. By the end of the fifth, the number was about $200,000.

But those slots, legally speaking, were mere recommendations, and baseball tried to enforce them with ham-fisted bluster and bullying. Here’s just one example: MLB used to send the Toronto Blue Jays payments to help adjust for the exchange rate, an old problem for an operation that takes in Canadian dollars but pays out U.S. Whenever Toronto went “over slot” to sign a pick, one of Selig’s lackeys would call: Jeez, I hope this doesn’t force us to rethink those payments.

It was a weak system, and under Epstein, the Sox exposed it as such by regularly going over slot. If you enjoy comparing baseball GMs to Civil War generals—and if you don’t, why the heck not?—let’s agree that Theo was our Ulysses S. Grant. While he may not have been the best tactician, he made up for it with discipline, focus, and a commitment to overwhelming his opponents with superior resources. When it came to player development, that meant borrowing John Henry’s jet for cross-country scouting trips and hiring more on-the-ground evaluators.