How Boston’s Olympic Dreams Flamed Out

In four short months, construction magnate John Fish went from Olympics hero to sitting on the sidelines. The inside story of how it all fell apart so quickly.

At the time, the unflattering press coverage seemed like a minor embarrassment, but it helped ignite a report that the USOC was so concerned about a Boston meltdown that it was considering yanking Boston’s bid and going with Los Angeles. On March 31, Scott Blackmun, CEO of the USOC, told the Wall Street Journal that “Local support is critical to the success of any bid,” in a story that reported the committee was “unlikely to move forward with the plan if residents continue to reject it.” Suddenly, it looked like Fish had only until September—when the USOC has to file the American bid—to turn the Olympic effort around.

The next morning, April Fools’ Day, Fish appeared at a Northeastern University breakfast to peddle the bid. This time, though, he added a new wrinkle, decrying the decline of patriotism in America and the need for an Olympic-sized booster shot. Afterward, a reporter for Channel 5 claimed Fish had questioned the patriotism of Boston 2024 opponents, igniting a social-media wildfire. Fish never said that, but his brand of patriotism went over poorly in a town where patriotic pride is expressed as much through public dissent as public display. It was Fish’s last Boston appearance on behalf of the Olympic bid.

Still, Fish couldn’t catch a break. On April 2, a Herald headline screamed that Mayor Walsh wanted the former athlete to take a diminished role as a so-called ambassador to cheerlead from the sidelines (a report Walsh denied). Fish bailed out of scheduled talks at a builders’ convention in April and then again at a hotels conference later that month. By the end of April, a consensus had formed: Someone needed to hit the reset button on Boston 2024 and take the reins.

Finally, Fish had to confront the idea that the bid was failing. On April 22, Boston 2024 announced its expanded all-star board of directors, including fan favorites Larry Bird, David Ortiz, and Meb Keflezighi. Fish also brought in the big guns, retaining crisis-management conglomerate Weber Shandwick both for himself at Suffolk and for Boston 2024. The firm’s top consultant, New England division president Micho Spring, was brought in to stop the bleeding.

In truth, Fish had already begun damage control. On March 27, he met with the governor and his cabinet at the State House, one of several private meetings between Boston 2024 and the state’s elected decision makers. When they emerged, all were tight-lipped about what they’d talked about, and Baker, who had maintained a steely skepticism of the bid in his public statements, softened to say he “thought it was helpful” and that the effort was “further along than the previous stuff I’ve seen.” Though no one would admit it at the time, Fish had shown them an expanded detail of the bid (it later became public thanks to an open-records request from former gubernatorial candidate Evan Falchuk).

The move to retain Weber Shandwick, however, came at a significant cost—in both optics and capital. The Globe whacked Fish again by suggesting there was a conflict of interest, since Weber Shandwick was now representing both the man and the bid. And Spring’s services don’t come cheap. Boston 2024 had already pledged to release its employees’ salaries, and now the Globe was demanding to know how much was being spent on the PR company. To date, they have not released the amount.

Boston 2024’s problems, however, may run deeper than any PR firm can fix. The two opposition groups—No Boston Olympics, headed by former Patrick administration transportation official Chris Dempsey, and No Boston 2024, headed by progressive activists—have driven the conversation around the bid. They’ve pointed out that the city will be required to cover any Olympics cost overruns Boston 2024 might incur. And they’ve questioned the feasibility of key venue sites, from the Olympic stadium and athletes’ village to the Somerville velodrome and equestrian events in Franklin Park. The more Fish and company respond that the bid is just a “proof of concept” that’s subject to change, the more critics warn that Fish is asking Boston to take a huge financial risk based on too many unknowns. Those arguments have been bolstered by major editorials in the Globe and Herald, as well as in CommonWealth magazine, and the op-eds of Smith College economics professor Andrew Zimbalist, who has practically become the state’s naysayer in chief. Now, Boston 2024 is pinning its hopes on a revised venue plan it promises to deliver by later this summer.

As the USOC nervously eyed the polls and pressed for a new strategy, Boston 2024 also enlisted two agencies—Teneo Sports and JTA—that specialize in advising Olympic bids. “Check your egos at the door,” Teneo copresident Terrence Burns warned Fish and other Boston 2024 executives shortly after being hired. The message was clear: They’d have to work together and not worry who got the credit.

Meanwhile, Boston 2024 needed fresh blood—and it needed someone who could stand up to Fish. The pressure finally culminated during a May 8 conference call, when Boston 2024 execs presented a reorganization plan. In his most humbling moment yet, Fish agreed to step aside as chairman, four months to the day after the U.S. Olympic Committee chose Boston. That plan, which was not yet final as Boston went to press, stands as his career’s most significant public defeat. Boston 2024 plans to tap two of the biggest names in Boston sports to step in. Steve Pagliuca, a Celtics co-owner and a managing director at Bain Capital, would move up from vice chairman to chairman. Larry Lucchino, the Red Sox president and CEO, would serve as a strategic adviser, as would Fish’s longtime mentor Jack Connors.

Pagliuca’s ambitions are as vast as Fish’s—he ran for the U.S. Senate in 2009, and came in last in the Democratic primary. But he’s a very different type of leader. Fish is a salesman. Pagliuca is a skeptic, a numbers guy. Now Pagliuca’s job will be to solidify the speculative Olympic venue budgets and plans into a more trustworthy bid.

Still, Fish hasn’t been forced out entirely—he plans to remain with Boston 2024 as a vice chair. Though he has not helped the Olympic effort when he pontificates in public, the privately funded bid needs his fundraising mojo. If he goes, so likely do many donors who trust him. On May 12, after months as the public leader of the Boston Olympic effort, Fish accepted the potential diminishment of his role with a one-sentence statement: “I am committed to doing all I can to bring the Olympic and Paralympic Games to Boston in 2024; and I will continue to work tirelessly to achieve that goal in whatever role is most appropriate.”

In spite of everything that’s happened, Fish continues to show up at his office at 4:30 a.m., look out at Boston’s skyline, and hope his Olympic dreams will come true. He knows that winning isn’t normal, that it takes extraordinary effort. So he’ll keep striving to make his vision a reality—but in private, where he works best.

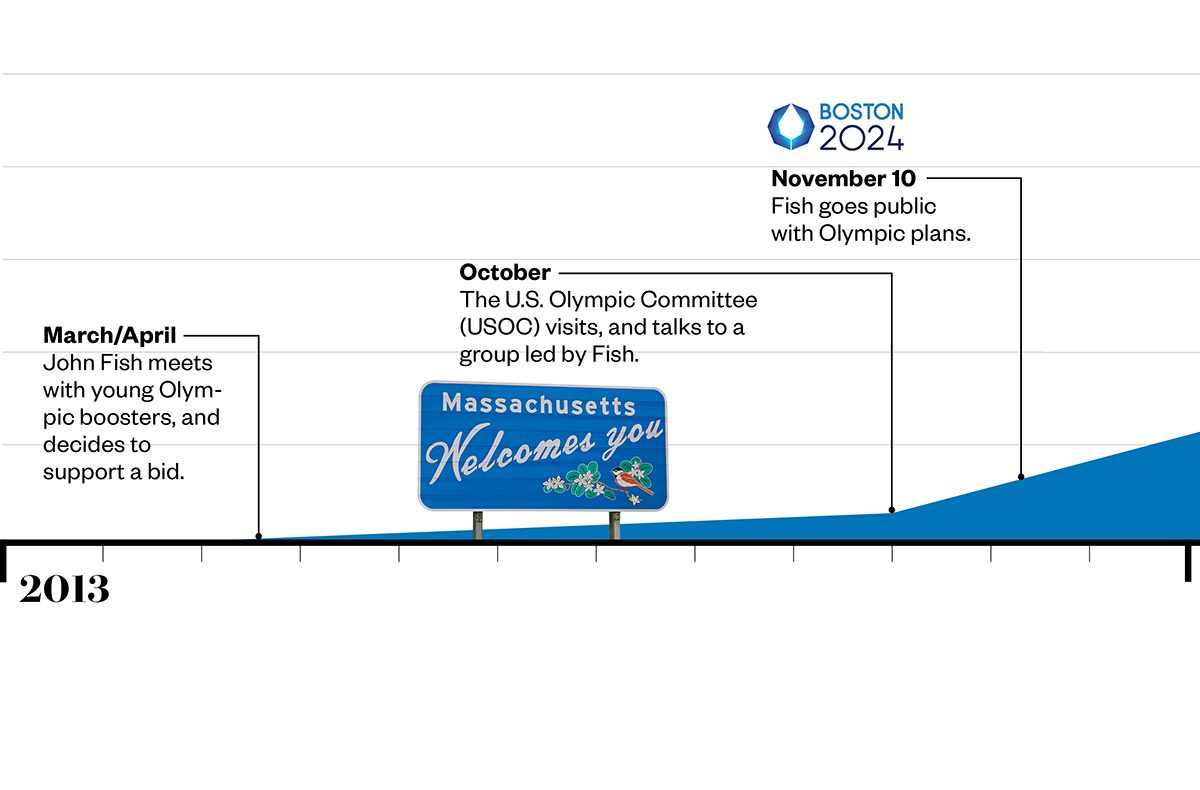

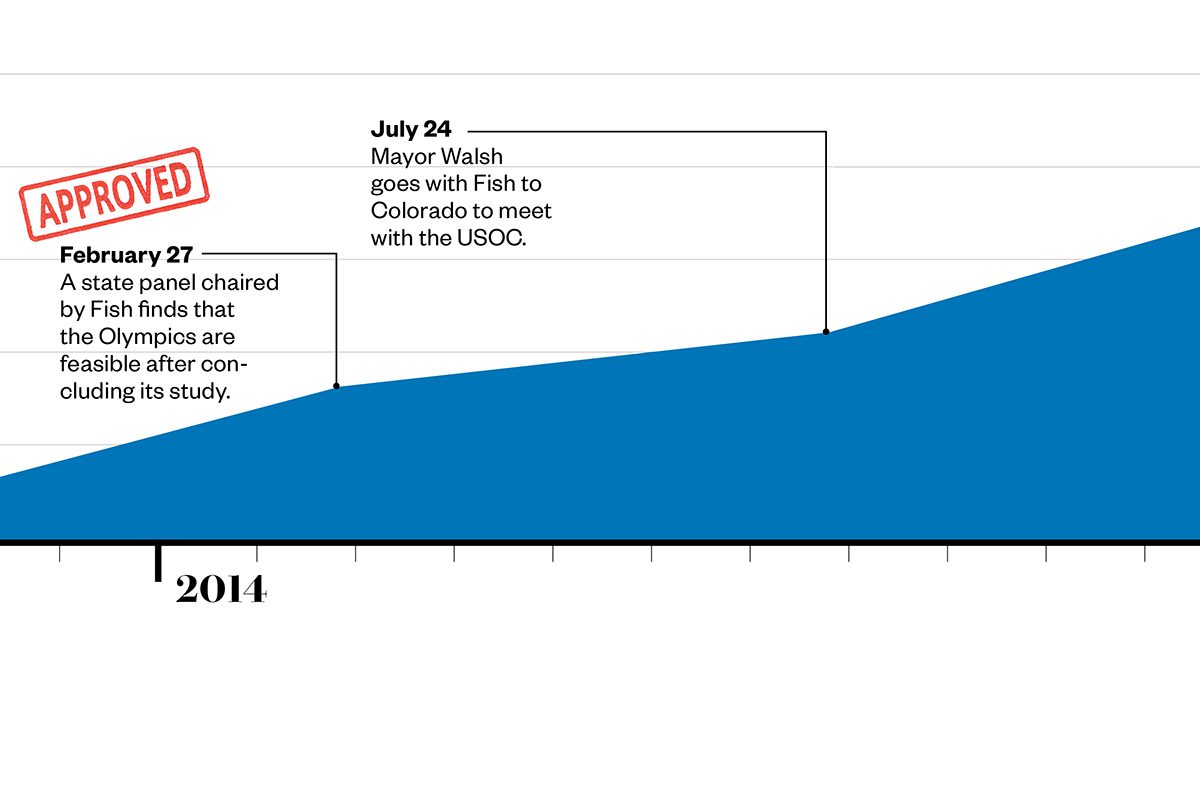

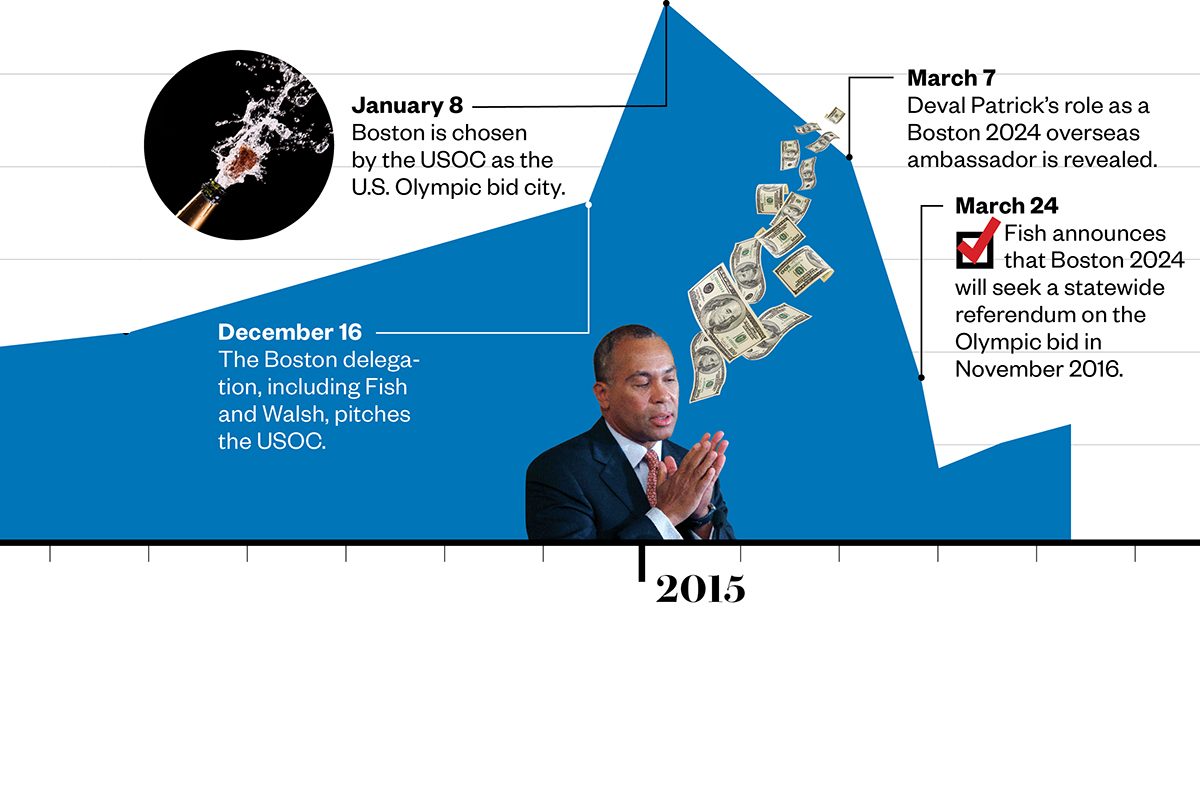

Olympian Clout

Our highly subjective chart of the meteoric rise and sudden fall of Boston’s Olympic dream.

photographs by AP photo/elise Amendola (patrick); jenny anderson/wireimage (kwan); Ron Hoskins/NBAE via Getty Images (bird); istockphoto (sign, stamp, champagne, money); Steven A. Miller/flickr; courtesy of boston red sox (ortiz)