Greg Selkoe’s Bad Karma

He built the nation’s hippest online clothing company into a $127 million e-commerce titan. When Karmaloop filed for bankruptcy in March, everyone wanted to know: How did it all go wrong?

Pharrell Williams (above left) signed on as creative director in 2010 to help launch a cable-TV channel similar to MTV. (Photograph by Theo Wargo/getty images)

When television executive Kate McEnroe, of Lionsgate, approached Selkoe in 2010, it seemed like a lucky break. At the time, cable giant Comcast was struggling to adapt to the advent of online streaming and feared new channels on YouTube might drain its viewer base. When the company ultimately received approval in 2011 to buy NBC Universal, it promised the FCC it would launch 10 new independent cable channels. McEnroe wanted Karmaloop to be one of them.

It’s really not as absurd as it sounds, Rayport says. Brands were becoming content marketers and, in some cases, content producers. In 2007 Red Bull launched a monthly magazine; the same year, Starbucks created its own label to release CDs; and in 2008 Mountain Dew launched its own record label, Green Label Sound. “If these guys were thinking, way back in ’07, Oh, you know, we can do a media site, they may not have known exactly how to realize their vision, but it wasn’t a crazy idea,” Rayport says. “Subsequent history has shown that content marketing is a strategy that many brands, including Amazon, have found compelling and effective.” Still, Karmaloop needed expertise—and cash. Experts at the time estimated that launching a cable channel would require at least $100 million in startup capital. Karmaloop had a fraction of that.

Selkoe’s plan for cable was simple: create an MTV channel for the new generation. “It’s not that our demo doesn’t want to watch TV, because they definitely want to watch TV,” Selkoe told Bloomberg News in July 2011. “It’s just that they don’t have anything on for them right now.” Selkoe and McEnroe envisioned making their cable content interactive—mimicking the Internet—to appeal to younger viewers. Pharrell Williams soon signed on as Karmaloop TV’s creative director, and Selkoe subleased 10,000 square feet in Manhattan for approximately $30,000 per month for his production company. At the same time, he was pursuing a strategy that seemed, paradoxically, straight out of 20th-century broadcast television: He spent money licensing old kung-fu movies from a company in Hong Kong and hired Hollywood’s powerful United Talent Agency.

Selkoe, Williams, and McEnroe met with Comcast executives in Philadelphia numerous times, but the cable company was slowly shifting away from the youth bid toward minority-owned channels that complied with the FCC’s “diversity” stipulation. In the end, despite lengthy negotiations with Selkoe, Comcast went with Sean “Diddy” Combs’s cable channel, Revolt, which launched in October 2013; director Ricardo Rodriguez’s El Rey Network; and Magic Johnson’s Aspire. Maybe, Comcast told Selkoe, a Karmaloop channel would happen in the next couple of years. But Selkoe couldn’t afford to keep the operation going. He’d reached for the sun and gotten scorched. As the CEO of a now cash-strapped company, Selkoe had sunk an estimated $14 million into the cable-TV bid, all of it suddenly down the drain.

The television plan had also been a major distraction from Karmaloop’s main retail business. After the Comcast deal collapsed, Karmaloop attempted to boost revenue and refocus on retail, launching as many new websites as it could as quickly as possible. Along with the trendy flash-sale site Plndr, Karmaloop added skater-oriented site Brick Harbor, higher-end menswear site Boylston Trading Co., women’s fashion site MissKL, and an “exclusive membership program” called Monark that, for $720 per year, sent members “a diplomatic pouch…with a limited edition” piece of clothing or jewelry. Many of these failed shortly after launch and were abandoned. One instant moneymaker, however, was a drop-ship marketplace, Kazbah, that offered small-scale brands the opportunity to sell their wares through Karmaloop, which in turn would skim off a percentage of the sale for the privilege.

Though the new websites could have been built cheaply on existing platforms, Karmaloop pursued a bespoke approach for each, challenging the bandwidth of its technical team and requiring more cash than the flagship site could supply. New websites and vendors also strained the company’s already shaky hold on its core business, as the executive team met daily, sometimes hourly, to roll out new online deals and reductions.

“The thing at Karmaloop was always: What’s the deal?” says one top-level employee who worked there in 2011 and 2012. “Was it 20 percent and free shipping? And they would change it within an hour. They would change it multiple times sometimes, with little blinking things when you’re ordering.” The company was fighting to drive revenue, he says, but sacrificing profits. “I mean, I can barely balance my checkbook, but I was like, this does not seem right to me.”

In 2012 Selkoe again turned to Insight for an infusion of cash. “We were begging, ‘You’ve got to help us,’” Selkoe says. “And they just said, ‘Look, we’re not.’” Several former employees say that by that time, Insight may have lost interest; the VCs had pressed Selkoe to replace Mastrangelo as COO, as well as hire a qualified CFO, but Selkoe refused to sack his longtime friend. Between 2006 and 2013, the company cranked through five CFOs.

In retrospect, Selkoe believes that Insight burned up Karmaloop in its attempt to get a huge e-commerce hit. “You’ve got to understand,” Selkoe says, “most businesses that get funded by venture capital don’t succeed. That’s how they make their money. Because they take so much of the business, and they say spend as much. They only want you to hit a grand slam, right? Or they don’t want you to make anything. It’s one or the other…. There was a desire for us to shoot the lights out…go big…. They either want that, or they want a huge flameout, one of the two.”

According to Selkoe, as far as Insight was concerned, there would be no additional funding. And it didn’t want the company to take on new investors, either, a move that would have diluted the VC’s stake in Karmaloop. Instead, to finance its continued growth, Karmaloop took on debt: a $19 million loan from Florida-based Comvest, and $13 million from Chicago’s CapX. For the first time ever, if Karmaloop defaulted, Selkoe could lose it all. “It’s a terrible thing to do if you don’t think you can come out the other end,” Rayport says of the decision, “and obviously they didn’t come out the other end.”

Selkoe’s company was spending more than it was taking in. Still unable to cover Karmaloop’s estimated $1.2 million in monthly expenses, including payroll and marketing, plus interest on their enormous loan, Selkoe and Mastrangelo went back to trying to scare up more shareholders. They’d never had trouble before.

Selkoe had always been good at finding money when cash was tight. In the early days of the company, before the venture guys showed up, he’d raised an astounding $55 million from hundreds of small investors: friends, family, neighbors, even guys on the street. Rayport, the HBS e-commerce guru, finds this feat extraordinary: “Raising $55 million in an angel round through what must have been dozens upon dozens of small transactions, that’s impressive,” he says. “It’s institutional-size investing, and it’s big even for a serious venture capital round.”

Over the years, employees remember Selkoe constantly asking for small-dollar, quick loans to tide the company over: $5,000 here or there. But this time was different. Selkoe and Mastrangelo approached more than 280 potential investors during 2013 and 2014, all of whom turned them down. Overwhelmed with debt, Karmaloop had become a toxic asset.

The company’s slow-pay model had always been a source of stress, but sometime in early 2014 Karmaloop stopped reimbursing the vendors who’d shipped goods directly to customers through the drop-ship site Kazbah. Now Karmaloop was keeping all the money to buoy its liquidity. As a result, many of the company’s vendors began to struggle. Selkoe sent an email to them trying to explain: “I put my whole life into Karmaloop blood, sweat and tear…and for some reason all the money I make seems to just go back in…cause well I am like you I like to build sh**! For those of you starting out you will see that the ups and downs of cash flow is a big part business…You have my word everyone will get paid and we will f****n kill it for you guys this year!”

But Selkoe had already hit the point of no return. In the summer of 2014, Comvest began pressuring Karmaloop to file for bankruptcy, which sent Selkoe’s team scrambling for short-term cash and shelter from creditors. The Selkoes took a $1 millon loan on their $4.8 million condo in the Back Bay. In the fall, Karmaloop unloaded its warehouse full of inventory on a competitor, the Collective, for $4 million. In February 2015, Mastrangelo transferred ownership of his condo to his wife. Back in 2013, Selkoe had begun to borrow large sums of money from his father, in up to half-million-dollar chunks. By 2015, Dennis and Polly Selkoe had fronted their son more than $2 million; according to financial records provided by Dennis, Greg repaid only slightly more than half of the money.

Shortly thereafter, Insight gave up its seats on the board, leaving Selkoe and Mastrangelo to fend for themselves. In October 2014, Karmaloop defaulted on its loan from Comvest. Eventually, the company was taking orders but couldn’t deliver the merchandise. Within months, the former e-commerce behemoth owed its own customers more than $2 million worth of goods. By the time March rolled around, Karmaloop could no longer afford to pay its day-to-day expenses. Out of options, the company filed for bankruptcy.

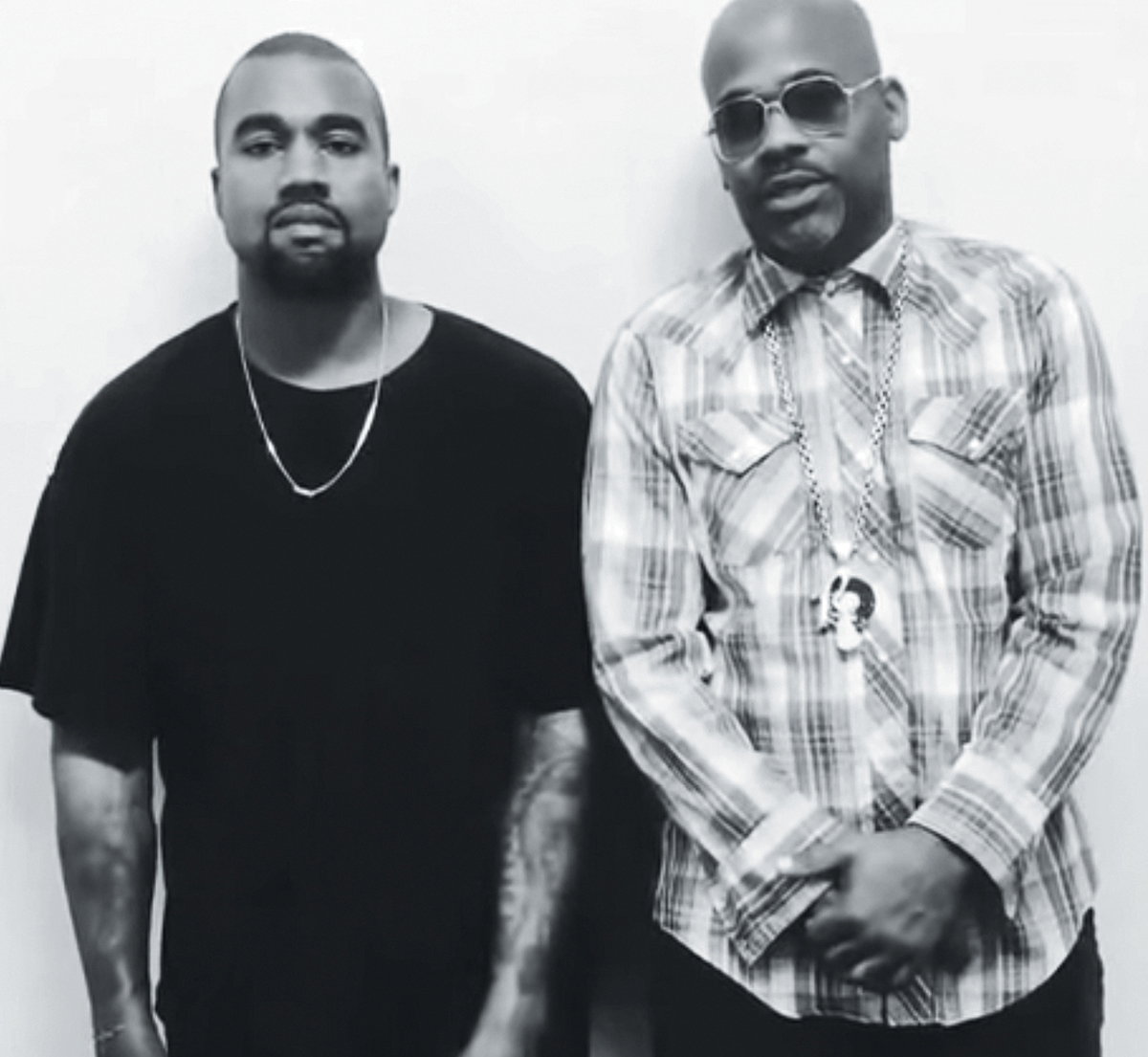

On March 23, hours after Karmaloop filed for Chapter 11, a pair of mysterious videos showed up on Instagram. Kanye West stood next to music executive Damon Dash, who mumbled his way through an announcement that “We decided to go buy Karmaloop. We just talked about it, so it’s going to happen.” Four days later, Selkoe tweeted, “I am still gonna be owner no matter what we do. I am Karmaloop!”

Selkoe was desperate to hold onto the company he’d built. If no one else stepped up, it would be sold at auction to the highest bidder—or, most likely, go to Comvest and CapX, which held a mountain of debt over the failing business. Selkoe suspected that Comvest didn’t want him running the company—believing that the firm was using a restructuring officer to undermine him.

For weeks, rumors swirled as publications from the Hollywood Reporter to the Wall Street Journal speculated on a Karmaloop-West union. Selkoe hoped his friend would come through, but now admits he “knew all along that [West wasn’t] going to be able to pull the whole thing together.” Instead, Selkoe flew around the country in search of a buyer who would take him as part of the Karmaloop package, meeting with several potential investors, including Magic Johnson’s group in L.A. Always upbeat to his adoring horde, Selkoe released a statement saying, “We’re having a lot of conversations and seeing intense interest in our brand.”

In the week leading up to the sale, Selkoe holed up in his office, anxiously pacing and talking on his phone as he tried to secure a last-minute deal. On the day of the auction, however, not a single investor materialized. West had vanished. After the auction, Comvest and CapX officially owned Karmaloop.

Left on the balance sheet were 96 people—Selkoe’s father listed among them—who had invested in Karmaloop over the years but never cashed out. Together, they were owed $55 million. Comvest believed its only shot at recouping its losses was to make Karmaloop profitable and flip it. The bank’s first action item: Ditch Selkoe as CEO.

Hours after Karmaloop filed for Chapter 11, Kanye West and music producer Damon Dash announced plans to buy the company. (image via youtube)

The following day, on May 22 at 2 p.m., Selkoe corralled the 60-plus remaining employees at the office into a loose circle.

After taking over, Comvest had told Selkoe what VC firms often tell recently terminated CEOs: They hoped to find a role for him in the company. True to form, Selkoe believed what the more-experienced businessmen told him.

Now, with his head down, he walked into the center and told the Karmaloop origin story—starting from his parents’ basement. He explained that Comvest wanted him out for 60 days while the company’s new CEO, Seth Haber, settled in. Selkoe warned that there would be layoffs and said that he wanted customers and vendors who’d been caught up in the bankruptcy to get paid. When he asked if anyone had anything to share, two junior employees thanked him. Then silence, followed by light clapping. Selkoe returned to his corner office overlooking Boylston Street and began packing his plaques, sneakers, and artwork—taking with him a valuable piece by Shepard Fairey.

He wouldn’t be coming back. Twenty-six days later, without so much as a phone call, the company unceremoniously deleted his email account. “I am saddened to no longer be welcome at the company I founded and in many ways still see as my baby,” Selkoe wrote in a final email to his former staffers from a personal account, “but over all I truly still feel happy today. I look positively to the future, remaining friends with all of you and eternally grateful for the time we spent together!”

After all, Selkoe told me without a hint of irony, “It’s like, when the suits aren’t running things, it does the best, right?”