Gloucester Police Chief Leonard Campanello Strikes at Big Pharma

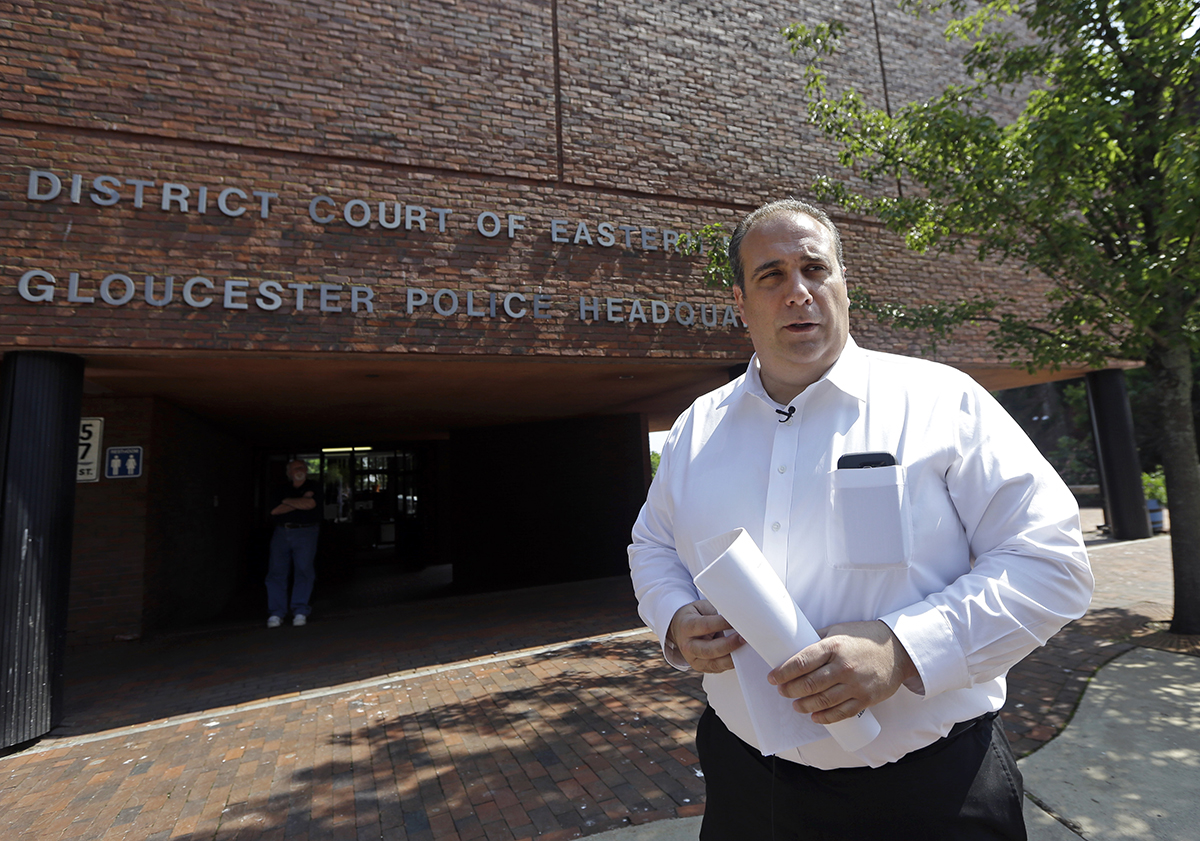

Photo via AP

Look out, Big Pharma. Gloucester Police Chief Leonard Campanello, who rocketed to national prominence this spring when he announced that his department would stop arresting opiate users in need of treatment, appears to have scored another victory in his crusade to temper the state’s heroin crisis and bring more resources to bear on an epidemic that’s poised to kill more than 1,000 people this year.

Last week, the small-town police chief took to Facebook and posted a message encouraging followers to call some of the world’s largest pharmaceutical firms and “politely ask them what they are doing to address the opioid epidemic in the United States and if they realize that the latest data shows almost 80% of addicted persons start with a legally prescribed drug that they make.”

In addition to the request, Campanello listed the salaries of the five highest-paid pharma executives and provided phone numbers for their offices.

It took only two days for Big Pharma to take note, and on Friday Campanello announced that Pfizer, whose CEO pulled in more than $23 million last year, has reached out to the department and agreed to meet. The other companies that Campanello put on blast were Eli Lilly, Merck, Johnson & Johnson, and Abbott Laboratories.

From the beginning, Campanello has been pushing Big Pharma to step up and help respond to the crisis, which has overwhelmed the state’s public health system. He has repeatedly referred to pharmaceutical firms as the “Exxon Valdez” of the opioid crisis for their role in manufacturing and marketing highly addictive pain pills that have contributed to a surge in drug abuse. “You make a spill, you gotta clean it up, and you gotta wash every penguin off that you affected,” he said during a recent interview with Boston.

Campanello and PAARI, the nonprofit he helped set up to support his pursuits, have been a wrecking ball in past months, knocking down barriers to care and shuttling nearly 200 individuals suffering from addiction into treatment. His Facebook posts have gone viral, making him arguably the loudest voice in the state, perhaps the country, when it comes to the opiate crisis, which claimed more than 1,200 lives in Massachusetts in 2014.

Since June 1, when the Gloucester program launched, Campanello and his team have attracted a legion of volunteers and constructed a continuum of care for drug addiction that has never existed in Massachusetts, or anywhere, really. His efforts have garnered support from addiction treatment centers around the country, which have offered up treatment beds and financial scholarships. A growing number of police departments throughout the country are now following the provocative police chief’s lead and have implemented similar programs.

Campanello isn’t done yet. In announcing that Pfizer has agreed to meet, he also noted that he and his ever-growing coalition continue to push for a prescription monitoring system that spans states as a way of going after doctors who overprescribe pain pills.

“There are entities who have to admit things were approached incorrectly and take part in correcting the system,” the most recent Facebook post read. “If they do that, law enforcement has no issues with them. We don’t want to be in the health care business…but we are really good at holding people accountable.”