‘I’m Robert Kraft. Do You Know Who I Am?’

Kraft has been shaping that particular legend—the Patriot Way—for a long time. The Patriots aren’t just a football team, but a family, one that preaches supremacy. And they’re about something more than winning. Really, that something is Kraft-dom. Himself. To make sure we remember, Kraft welcomed NFL Films in 2009 to spend a whole year in Foxboro with Belichick documenting the Patriots’ inner workings because, as Kraft said then, he wanted “someone to be able to see 100 years from now exactly what the team had done.”

Now the Patriots are one of the top franchises ever, given this century’s four Super Bowl wins. Dominating is the bottom line. “After the love of my family, there’s nothing more important to me than winning football games,” Kraft said last year. “And I will do whatever I have to do to put this team in a position to do that.”

But there’s a fine line in pro sports when it comes to what exactly whatever encompasses. When Belichick was caught spying on other teams’ signals to their players from the sidelines in 2007, which is cheating, Kraft asked him, “How much did this help us on a scale of one to 100?”

“One,” Belichick answered.

“Then you’re a real schmuck,” Kraft said.

Kraft shared that little snippet with a sportswriter as proof of both his ignorance of the misdeed and his disapproval of it. Notice, however, that it avoids condemning Belichick. No, the coach of the New England Patriots may have broken the rules, but his mistake (in Kraft’s world) was doing it for such small gain. That’s the opposite of the Patriot Way. Last month, ESPN published an exposé on Spygate, claiming that the Patriots had taped other teams’ signals over many years—far longer than was previously known—and that the league’s response to it had amounted to a cover-up. The Patriots have denied the substance of these latest accusations.

The Patriot Way must always emerge flawless from even the murkiest waters. When Patriot Aaron Hernandez, a massively talented tight end, was charged with murder in 2013, Kraft said that he had been snookered by the player, who would often greet the owner with a hug and kiss. “He was a New England kid who was a Patriot,” Kraft once said. “I thought it was cool.”

In fact, the Patriots knew Hernandez had failed a drug test at the University of Florida. Scouts for other NFL teams now say that it was also known around the league that he’d been questioned by police about a shooting outside a nightclub, that he’d once ruptured a man’s eardrum in a bar fight, and that his buddies from the streets of Bristol, Connecticut, would show up to hang with him. Those teams avoided him during the draft.

“No one in our organization was aware of any of these kinds of connections,” Kraft told the Globe. The team had signed Hernandez to a $40 million contract extension a year before the murder charge. “If it’s true,” Kraft said of the charge, “I’m just shocked. Our whole organization has been duped.”

But Tom Brady is untouchable. Kraft says he loves the quarterback like a son—one who embodies everything, in skill and class and demeanor, that the Patriots and Kraft stand for. From 2000 through Super Bowl XLIX, Brady’s record as QB has been 182–56, a marvelous run. But then he was accused of telling minions to reduce the air pressure in footballs to make them easier to grip and throw. It seemed so…insignificant.

Deflategate revealed the fragility of Kraft’s legacy, and he became desperate to save it. A few days before the Super Bowl, the owner defied the NFL’s “protect the shield” ethos when he issued an ultimatum: If the league didn’t have hard evidence that the Patriots had cheated, he proclaimed, it would owe the team an apology.

In demanding contrition, Kraft knowingly violated the code: In pro football, everyone guards the golden goose. The NFL does not apologize.

Kraft had had a strong relationship with commissioner Roger Goodell—in the league office, Kraft had been dubbed “the assistant commissioner”—but he was deluded if he thought he could strong-arm Goodell now, especially given that the commissioner was trying to recover from a few screw-ups himself. In fact, by coming down hard on his old chum, Goodell was proving that he didn’t play favorites.

In May, he punished the Patriots not only with a four-game suspension for Brady, but also by stripping the team of two draft picks and docking Kraft a million dollars. A week later, at an owners’ meeting, Kraft discovered that other owners—weary of the Patriot Way—didn’t have much sympathy for him.

Two months later, when Goodell refused to budge on appeal, Kraft continued his assault on the NFL. In a 650-word statement of controlled rage, he said, “The decision handed down by the league yesterday is unfathomable to me…

“I acted in good faith and was optimistic that by taking the actions I took the league would have what they wanted. I was willing to accept the harshest penalty in the history of the NFL for an alleged ball violation because I believed it would help exonerate Tom.”

Kraft—at least until all the legal niceties play out—has finally gotten his wish; he can now claim that a judge exonerated Brady. But we learned a lot about Kraft along the way. He seemed not just angry that the NFL so willingly played fast and loose with flimsy evidence against Brady. No, it was much more than that: Kraft was beside himself with the notion that something like this could happen to him, as if none of us—the league, Goodell, the fans, the world—understands just who he is.

Kraft attended the 40/40 Club 10-year anniversary party with Jay-Z in 2013. / Photograph by Anthony Behar/AP Images

Harry wanted his son Bobby to become a rabbi. Kraft got rich instead (he’s now worth $4.3 billion). Did he take the lesser path? I pose that question to Steven Comen, born the same year as Robert in the same Brookline neighborhood. Comen became a lawyer, and Robert was a client at the time he bought the Patriots.

Comen considers my question for a minute, then says, “Doing good and achieving was in the water we drank. And how that got translated—it was translated by children in different ways. Some may have become doctors, and some well-known doctors”—like the surgeon Avram Kraft, still practicing in Chicago—“some may have become businesspeople achieving in different ways.”

The “doing good” part—well, Robert and Myra covered that by giving away more than $100 million over the years: $20 million to Partners HealthCare in 2011 to attract doctors to community health centers, $25 million to Harvard Business School to help scientists get their ideas commercialized (commemorating Robert’s 50th and his eldest son Jonathan’s 25th graduation anniversaries). Kraft writes checks to the United Way, the Boys and Girls Clubs of Boston, which his son Josh heads, and charter schools.

“Achieving,” especially in business, however, comes with built-in ethical questions. There have been dark rumblings, especially 20 years ago when Kraft bought the Patriots, that he is ultra-aggressive, that he pushes deals to the max. The oft-told story of how Kraft got control of the land around Foxboro Stadium, and then bought the stadium itself in order to keep the team here, proves that he has a taste for calculated dealing. And then he figured out how to create an organization that wins, first battling with coach Bill Parcells and ultimately hiring Belichick.

Some claim that Kraft uses his natural charm as a weapon. A Boston businessman who long ago grew sick of dealing with him says, “He comes on very strong. The first thing he does is ingratiate himself: ‘Look at you, that’s a nice tie, and the lapels of your jacket—that’s nice material.’ Some people are too much in your face, and Bob is one of those guys. He came across as very phony. I once had an argument with him about something and told him, ‘You are the most insecure person I’ve ever met! You should see a psychiatrist!’ It was the way he had to fight for everything.”

Charlie Sarkis, the longtime restaurateur who has fallen on hard times, negotiated with Kraft about leasing a track next to Foxboro Stadium for harness racing. He once complained to the press, “He used to say to me, ‘I like you because you’re a family man.’ Then, when I was sick he figured it was the perfect time to strike.”

I talk to a couple of guys who did business with Kraft during that same period, in the ’90s. One says, “Kraft only looks out for one person—it’s hard to have a partner like that.” Another: “He’s out for only one person, and that would be Bob Kraft.”

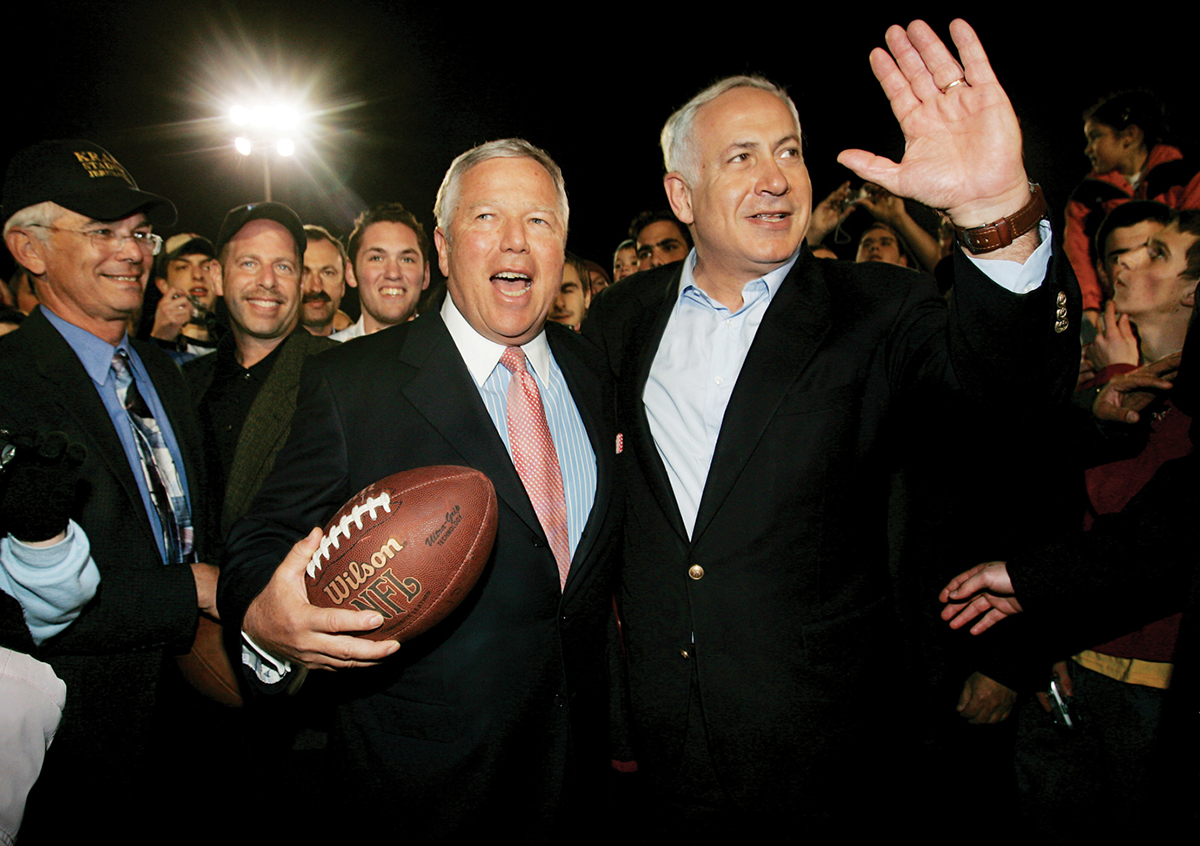

Kraft palled around with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, right, during an event promoting the Israeli flag-football league. / Photograph by Kevin Frayer/AP Images

Long ago, as he started getting rich, Robert Kraft found a place that needed everything he had to offer—his power, his money, and his philanthropy. In Israel, he would gain the ear of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who consulted him not just for economic insight, but for his political viewpoint as well. Shai Bazak, a former Israeli consul general in New England who got quite close to Kraft, says, “Leaders in Israel consult with him because he understands the American mentality, in relations between Israel and the U.S. He’s a very clever and thoughtful person.”

Kraft had often discussed with his four sons the best way to support the country, and he finally settled on creating economic interdependency between Israel and Palestine, between Jews and Arabs. In 1989 he gained a controlling interest in Israel-based Carmel Container Systems, which he would build into the largest packaging company in the Middle East. To carry out his sociological mission, Kraft farmed out some manufacturing to Palestinian territories, ultimately without much success. But by the time he sold it in 2008, Carmel employed nearly a thousand workers and grossed some $600 million annually; better yet, says someone close to Kraft, it gave its owner a great deal of “psychic income.”